Americanism Redux

October 31, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Standing in the place we could not have imagined, thinking the thought we vowed would never be known. Halloween, 250 years ago, today.

* * * * * * *

(where this Word was spoken)

Eyes wide open, then blinking hard. Lump in the throat, then swallowing hard. Sitting uncomfortably, then shifting hard. You do what you do at a moment like this.

It’s how the people of Westborough, colony of Massachusetts, are reacting in the pews of the small church. In front of them and slightly above them is Reverend Ebenezer Parkman, widely respected and somewhat cautious in his response to the imperial-colonial crisis that has engulfed their lives.

Parkman’s sermon hits them in the face, like a bucket of water, of rocks, of hot coals, of razor blades, of…you complete the sentence.

Are you hearing this?

His theme is Revelations, Chapter 13, Verses 1-10, about the Beast that gets power from the Dragon and for forty-two months rules the world, except for a handful of people who defy it.

“Who is like the beast? Who can wage war against it?”

After Parkman’s sermon, the people file out of the small church to prepare for All Hallow’s Day.

* * * * * * *

(a house on Orne Street)

Aroz Orne, 43-years old, lives in Marblehead, colony of Massachusetts, the latest in a family of seafarers. He is a successful merchant and veteran legislator in the public affairs of town and colony. He’s still healing his inner wounds—the smallpox inoculation treatment facility he helped found and build is closing. The hospital became entangled in local fury over smallpox, with many people fearing the facility and its approach to treatment caused the disease. Orne had been the target of a lot of hostility and ill-will in the ordeal. He was gutted of public spirit. Perhaps not surprisingly, he’d rejected the offer of being a Massachusetts delegate to the special Congress meeting now ending its work in Philadelphia.

Today, 250 years ago, though, Orne takes a deep breath and begins the third day of a new public responsibility—he’s one of the members of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress to be named to the “Committee of Safety.” This sub-group of the Provincial Congress is tasked with putting the colony on a war-footing. Orne and his colleagues are to organize all things military, including supplies, artillery, ammunition, and volunteer-militia unit training. Every speck and shred of it is in defiance of British imperial orders and authority as embodied by Governor General Thomas Gage.

In less than a year, Orne the civic-minded merchant became Orne the publicly-ridiculed innovator who is now Orne the proto-revolutionary outlaw. And yet he’s still the same man.

* * * * * * *

(from three men in this town)

Burning in a blaze and rolling like the waves, this is the air and land of the colony of Massachusetts. In metaphoric terms, of course. Life is on fire and the things that you thought were stable and unshifting are overturning and overturned. You see the reddish-orangish glow coming toward you. You hear the crash of cups and crockery as they fall off the shelves and smash onto wooden cabin floors.

Three men tell the tale in the hours before All Hallows Eve.

A man in Boston realizes war not only is possible but war now also is probable. He writes in despair, “How would such a Thought have shocked us all a few years ago!”

A second man observes that the people who supported the pro-imperial authority but now-former governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson, are either making forced public recantations or they are packing up their possessions and moving into Boston near the encampments of British Redcoats. It’s one or the other.

A third man watches people gather up muskets and pistols, take them to craftsmen for maintenance and repair, and then turn out daily or semi-daily for military training with refurbished weapons.

* * * * * * *

(his signature)

A letter from James Lovell to Josiah Quincy is traveling on a ship in the Atlantic Ocean, five days out of Boston. Course heading: east. Destination: England. Contents: “If the people of England, our Fellow Subjects, will cease obstinately to shut their Eyes upon the Justice of our Cause, we ask no more; Conviction must be the Consequence of a bare Admission of the Light.”

In other words, Lovell believes that if only the people of England will see clearly what is happening in Massachusetts, they can’t help but agree it is awful and will work to stop it.

Yeah right, if only, says the goblin to the ghost.

* * * * * * *

(the birthday boy)

John Adams is twenty-four hours past his birthday of October 30. Now 39-years-and-one-day old, he’s traveling back home to southern Massachusetts from his time in Philadelphia and the ending of the special Congress. As of today, 250 years ago, his return journey places him in New York City, where he makes the following observation:

“The Sons of Liberty are in the Horrors here. They think they have lost ground since We passed through this City” (several weeks ago en route to Philadelphia).

Over the past two months, the colonial cause has weakened on Manhattan Island.

* * * * * * *

(a high wire over this town)

Want a deeper sense of how crazy things are becoming? Try walking the tight rope laid out by a writer called “Homespun” on October 31 in the town of Charleston in the colony of South Carolina.

First: every person should have the right to attend public meetings and speak their minds.

Second: every person should recognize that they are an American and a Carolinian and not descend into squabbles about being anyone else.

Third: but if a stranger appears who seems capable of persuading ignorant people into doing the wrong thing, they should be cast out.

Fourth: watch out for people who rely on impressive vocabularies and intricate arguments and prefer instead those who speak plainly.

You’re a high-wire talker if you can follow that path.

* * * * * * *

(what goes on in this Farmington home?)

Life in the Gridley home in Farmington, colony of Connecticut, is little less than hell.

Catherine Gridley may be at the end of her choices. She’s resorted to writing and publishing an account for printing in newspapers. Maybe it will save her life. Her husband, Samuel Gridley, has threatened to kill her. He’s verbally abused her three children from a previous marriage. He’s refused to change his years-long habit of leaving their home, returning, and leaving again for months at a time. He’s critical of her beyond all boundaries of decency. He’s denying her possession of most of her clothes. He’s ordered her to sleep on the floor.

The Gridleys are a family in word but not in life.

Catherine wants you to know and wants you to help.

* * * * * * *

(Normandy beaches)

James Tait lives along the Chesapeake Bay, a recent immigrant from Europe, and has sought help of a different kind. He has a special skill and today he’s publishing an article that he’s translated from French into English with an expectation that a market for his talent will open up.

The article is a detailed description of how they make salt on the beaches of Normandy.

Tait, a salt-maker of long experience—seasoned, some would say—wants the legislators of the colony of Virginia to consider sponsoring his craft in each Virginia county. Given the dark tone of the times and the invaluable role that salt has in diet, preservation, and health, Tait reckons his skill has found an important outlet.

A dash of salt in the pumpkin soup makes for a savory Halloween.

* * * * * * *

It’s October 31, 250 years ago, in a world of growing fright and potential terror.

Also

(by Dawe’s hand)

Six children pack the Dawe home in London, England. It’s an active and bustling family. Barely a day goes by in the Dawe house without seeing one of the kids with a quill pen or rough piece of chalk in their hands and a drawing on a sheet of parchment paper. It’s a family of drawers, artists, and sketchers. They see it and they draw it.

The father and husband and political cartoonist, Philip Dawe, is finally done with what may be his masterpiece. Truly. The image grabs you, kicks you, pushes you. At the same time, though, the power of the drawing is in how readily it portrays the day of publication more than the day of occurrence. It fits even more naturally into this year’s tenth month than it did in the first month.

Today, 250 years ago, Dawe has drawn a political sketch he’s entitled “Boston Paying The Excise-Man, or Tarring & Feathering.” Wow. It hits the public with as much force as any essay, article, pamphlet, or book. Likely more.

You don’t need much background knowledge to have a reaction to Dawe’s imagined scene of January 24 and the colonial protestors’ treatment of British customs agent John Malcolm.

Dawe would be exactly the kind of person “Homespun” on the western side of the Atlantic Ocean would want barred from attending a public meeting.

* * * * * * *

(the teenager’s monument)

He’s 18-years old. He and his father are on the run. Measure the length of he and his dad’s life by the hour, or if they’re truly lucky, by the day.

The teenaged son is Salawat Yulayev. He loves to sing and write poetry. That is, he loves these pursuits when he doesn’t have a gun or sword in his hand, when he’s not fighting alongside family and friends in the bleak woods, valleys, and mountains of the Volga River and the Ural Mountains, when he’s not offering his life up to the cause of breaking away from the rule of Russian monarch Catherine the Great.

The primary leader of the uprising is dead. Teenaged Salawat Yulayev is one of the few leaders still remaining free. The monarch’s soldiers are hunting him down, today, 250 years ago. If, or when, they seize him, he will be purposely kept alive. The monarch will want an example made of him.

An unmistakable display of unspeakable clarity. You can have hauntings well past the end of October.

For You Now

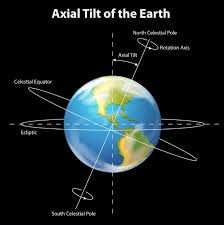

(on a new axis)

Let’s go to the birthday boy, John Adams. Same place, coming and going. Eight weeks ago he arrived at New York City on his way to the special congress in Philadelphia. Eight weeks later he’s in New York City again, retracing his steps on the voyage back home. Over the course of those two months, an American union has been conceived in Philadelphia, while supporters of colonial rights in New York City have judged their influence, persuasion, and strategic positioning to have deteriorated.

A similar pairing of shock awaits him in Boston as the town has transformed from social distress into a scene of war, as yet unwaged but hurling full speed into readiness and preparedness on both sides.

Two months and the world spins on a new axis.

Sometimes we assume that it’s real. It usually isn’t. But sometimes we assume that it’s real and it certainly is, not often but every once in a while.

How can you tell when it’s one and when it’s the other? My best advice: set aside the personal context of your day, like Adams did, listen to people involved on the ground, like Adams did, and watch what people are doing differently, like Adams did.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: lay two things alongside each other—one, how much have things changed in the past two months, and two, how much could you imagine things changing in the next two months.

(Your River)