Americanism Redux

October 3, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Look around. You’re seeing it sinking and seeping into everything. All around you.

Think you can avoid it? That really doesn’t seem likely.

You’ll need to figure out what it means in your life, for your life.

* * * * * * *

(Gurnet Lighthouse)

Would you believe it? They’re still bringing tea in!

A shipment arrives on a British fishing schooner in the Atlantic waters off Plymouth, colony of Massachusetts. The plan of the tea shippers was to land the stuff at night and sneak it into Gurnet’s Woods for distribution. Someone tipped off the local “committee of inspection”, the pro-colonial rights group in charge of enforcing the tea-protestors’ informal ban of the substance. Committee members seized the tea and dumped it into the ocean, and rounded up the perpetrators in the darkness.

With the contraband tea thoroughly salted, the committee goes back to ensuring that people continue to gather weapons of all kinds and begin practicing at marching, maneuvering, and firing. Maybe at the next training session, someone will bang a drum or play a fife.

* * * * * * *

(Gage)

North of Plymouth, at Salem in Massachusetts, British General and imperial governor Thomas Gage wrote yesterday to the Earl of Dartmouth “I do not find that the spirit (of protest) abates anywhere, for it is kept up with great industry. They are shortly to have a Provincial Congress in this Colony, composed chiefly of the Representatives lately chosen to meet at Concord, where it is supposed measures will be taken for the government of this Province.”

* * * * * * *

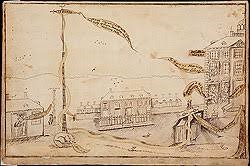

(a Liberty Pole)

Step out of Massachusetts and go to any town or village in the colony of Connecticut and the chances are good you’ll see a “Liberty Pole”, tall, wooden, carefully planed. Made of white pine and often upwards of a hundred feet or more in height, it will be pointing skyward in the center of the buildings that comprise the community. Morning, noon, night, people walk or ride by on horses or in horse-drawn wagons and see the Pole.

They know precisely what it means: we support our rights and liberties as colonists and residents.

The “we” might be a little tricky. So, too, might be the list of things that constitute “rights and liberties”. And how far “support” extends—what is allowable and acceptable in the moment of action—could also be open for discussion.

But to see the white-pine Liberty Pole in all its starkness and plainness, well, there’s not much to misunderstand.

* * * * * * *

(a white oak tree)

It’s not a pole in the middle of a Connecticut town. It’s a tree in the middle of the eastern Pennsylvania woods.

A white oak tree.

It’s the central marker for a swath of land in Chester County, colony of Pennsylvania. John Morris has declared his intent to finalize the survey of the property. He tells you to start at the white oak tree.

From that one white oak tree, a series of six other measurements and markers must be followed in order to trace the boundary and shape of the acreage. The route leads back to the white oak tree, making an unusual 50-acre shape.

Full-leafed, deep-rooted, and true green with only a few signs of color changing to red or orange, this single white oak tree is the beginning of everything you need to know about this land parcel.

From the white oak tree, John Morris will start envisioning plans for this land—the house, the workshop, the barn, the inn, the church, the meadow for livestock, the field for crops, or the appeal for re-sale or subdivision.

So, which is the more fundamental to the people of these colonies: the White Oak Tree or the Liberty Pole?

* * * * * * *

(John Smalley)

(Israel Putnam)

Two people in Connecticut try to repair their reputations today, 250 years ago.

One such person is John Smalley. He’s a minister in a Protestant church in, of all place-names, New Britain, colony of Connecticut. For the past four years Smalley has struggled to explain to people his views (theory?) of ultra-passive, peace-based, and harmony-driven opposition to whatever British imperial policies they deem noxious. Protest if you must, Smalley says, but only and always in non-threatening and non-disruptive ways. Well, as you might guess, people in New Britain who hate the Tea Act and the Coercive Acts have heard and seen enough of Smalley’s ideas. They’re ready to run him out of town. Smalley’s last hope is to present his case one more time in a local newspaper. His explanatory letter comes out in tomorrow’s edition.

The other such person in Israel Putnam, of the village called Pomfret. Putnam is well-known as a colonial soldier skilled in irregular fighting, a local warrior experienced in the combat life of Native American warriors. For him, the problem was that he went too far in the “powder alarm” of a few weeks ago; Putnam exaggerated a small gunpowder-seizing operation of Gage’s British Redcoats into a vast land- and sea-based enemy invasion of Boston and various colonial communities. People had grabbed muskets, pistols, axes, knifes, and hammers and spilled out of their homes in panic, expecting to see thousands of Redcoats ready to attack. Like Smalley, Putnam has chosen to write (or work with someone else to draft) a long letter of explanation of his mistake and, frankly, deflection of blame. It’s in the newspaper for anyone to read.

One isn’t going far enough in active protest. The other went much too far in empassioning people to the point of violence.

Somewhere between them is the balance, a microscopic object, invisible when it wants to be, weightless, hovering, with a mind and matter all its own.

* * * * * * *

(the mean streets)

You’re walking the mean cobblestone streets of Philadelphia. A guy comes over…

>Psssst. Heard about the pins and the pepper and the gunpowder?

–No, what’s going on with them?

>Prices for them are up, way up, just the last couple of days.

–Any idea why?

* * * * * * *

(inside Carpenters’ Hall)

The reason is an informal report—we’d call it a leak in 2024—that whatever else the “congress” does in Philadelphia, it will ultimately decide to ban importation of goods and services from England. That will be the chosen colonial reaction to the British Coercive Acts (mid-’74), which were the British punishment of the colonial tea protests (late-’73), which responded to the British Tea Act (early mid-’73), first enacted to support the British East India Tea Company during a European financial melt-down (mid/late-’72).

You followed that chain, I assume.

Follow something else, too, the effects of the price hikes. You’ll feel their effect in your ability to use your guns in hunting and home defense; your ability to cook food with taste; and your ability to extend the use of your cloth and clothing. And that’s just for starters. The prices on more items will rise.

And they’ll do so in town after town after town, across regions north, central, south, and the mountainous interior.

The whole crisis is soaking in.

* * * * * * *

(Joseph Galloway)

Delegates to the Congress (they’ve given themselves a capital “C”) are discussing a plan of colonial union authored by Joseph Galloway. They’re also dividing into committees to debate a petition of grievances, a program of non-importation, and an address that describes colonial willingness to pay their own governing expenses within the British Empire, which includes organizing their own war-making ability.

* * * * * * *

(the gunpowder that was hard to find)

A war of the west edges closer. The twin invasion forces, one led by Virginia governor Lord Dunmore and the other by his subordinate, Colonel Andrew Lewis, continue inching along separate paths into Shawnee hunting grounds of the upper Ohio River valley. Dunmore and Lewis want battle. Meanwhile, Cherokee Native warriors are threatening the scattered British colonial farms and villages along the Clinch and Holston Rivers. Colonial families near the Clinch and Holston are terrified because older men–husbands, fathers, and so on–have left to serve with Dunmore and Lewis. The shortage of men is worsened by the shortage of gunpowder, again a consequence of Dunmore’s force having gathered most of the available supply for their invasions.

* * * * * * *

A condition of no boundary and every consequence, that’s what is spreading throughout the American colonies and changing the way life is lived there.

Also

(the man who persuaded Franklin to stay)

In London, Benjamin Franklin was all prepared to finally leave England and return to the colonies. He’s suffered nearly a year of outcastness, the result of his earlier public humiliation this past January in a Parliamentary hearing. Only hours before leaving, however, an observer notes that “the Earl of Chatham sent for him, and after a long conference convinced him of the necessity of his deferring his embarkation until after the next Session of Parliament, in which that nobleman, aided with his intelligence of the proceedings of the colonies, intends to make the most vigorous efforts in favor of this country (the American colonies).”

Franklin listens. Franklin considers. Franklin stays.

* * * * * * *

(an ancient practice)

Esselen Natives are at work outside the walls of the Spanish presidio at Monterey on the Pacific coast. They’re setting fire to grass and brush that has accumulated and died over the summer. For generations the Esselen have burned off the old ground cover with the end of the warmest part of the year. They hunt down the rabbits flushed from warrens by the fire. They’ll also soon see among the ashes the brilliant green of seeds planted.

Spanish officers and soldiers inside the presidio see the smoke. Some of them ran out the gates to stop the burning. They believe the fires are a sign of the Natives’ primitive condition. If the Natives raised livestock, the Spanish insist, they would not have time to start these fires. The Spanish scoff further at Esselen men and women for failing to store food for future consumption. Theirs is a belly-driven existence, say the Spanish, who first saw Native-set fires more than two hundred years ago today in 1774.

* * * * * * *

(her way of living)

Compared to the Esselens, 18-year old Queen Marie Antoinette in France has the opposite problem but a similar spirit. She’s interested in today’s desires, cravings, and impulses, though with more money to spend than things she can spend it on. The latest gowns, dresses, shoes, purses, fans, jewelry, gloves, hats, and hairstyles are only a few of her luxurious purchases. She obtains the funds from her husband Louis XVI, the French monarch since the summer. He gave Marie her own palace, Petit Trianon, which she is settling into at Versailles. Marie has assembled most of her personal entourage at Trianon, including Princesse de Lamballe as her superintendent of household. It has taken only a few months for news of Marie’s habits and manners to become fodder for talk along the streets of Paris.

For You Now

(in 1924)

Another American recognized the anniversary of the Congress in Philadelphia, late September and early October 1774.

He was President Calvin Coolidge a hundred years ago right now, in 1924, just a few weeks away from the presidential election of that year. He had been Vice-President under a POTUS in frail health who died in office. Now, as the succeeding occupant of the White House to finish the term, Coolidge seeks the presidential election on his own. He’s been asked to speak at the 150th anniversary of the Congress of 1774.

I’ll give you three quotes from the speech (full text is here: https://coolidgefoundation.org/resources/address-on-the-anniversary-of-the-first-continental-congress/ :

“Your heritage has that mysterious quality by which it has enriched not only our own citizens, but the people of the earth…”

“If we could better understand what they said and did to establish our free institutions, we should be less likely to be misled by the misrepresentations and distorted arguments of the hour, and be far better equipped to maintain them…”

“The only position that Americans can take is that they are against all despotism whether it emanate from a monarch, a parliament, or from a mob…”

Coolidge also devoted substantial portions of his speech to emphasizing the role of moderation, carefulness, and prudence in the Founding actions of 1774, 1776, and 1787. He turned the issues of his era—production and distribution in the economy, for example—toward the light of the Congress’s experience in Philadelphia. He reminded his audience that American government is limited government. The people’s control of the government and their property were at the core of the ongoing American Revolution.

Finally, a word on the whispers of Coolidge. His terminology reflects an urgency we should understand for our own time. Pay attention to the appearance of “mob” in his trilogy of despotism’s sources. The word is Coolidge’s quiet reference to the mob of 1924, the Ku Klux Klan. He was dealing in his own time with a later version of savagery by the faceless, graceless, soulless gang of fellow brutes. The same quiet invocation applied to Bolshevik Russia, underscoring Coolidge’s emphasis on “production and distribution” as basic economic challenges in need of active civic improvements. The guidance of the Founding was needed because the dangers of the world were relentless.

To my knowledge, no major American leader in 2024—let alone the President of the United States—has had the wherewithal to bring our 250th anniversary forward to the current moment, the current times. A sad truth. And of course, if anyone had, my expectation is zero—sub-zero, in fact—that a Coolidge-like level of insight and thoughtfulness would be attained. Another sad truth. I propose that we do what we can which, in this instance, is to devote a few minutes to dust off the real deal and read it for yourself.

When traveling into the American past, both Lincoln and Coolidge deploy versions of the same Greek word “musterion”—meaning, of hidden origin—to probe the Founding. The mystic, the mysterious. So much to be known in the dark space of gone time.

Where once there were leaves of tea, drifting downward in the salt water, within sight of Gurnet Woods.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: is there a link between the Liberty Pole and the White Oak Tree? and a rare follow-up question: what would our POTUS say about today’s 250th anniversary?