Americanism Redux

December 12, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Time has a way of warping things.

You look back on two things in the past. Thing One happened before Thing Two. When you see it from now, Thing Two seems utterly natural, smooth, and free-flowing after Thing One.

That’s a warp, and usually not a reliable way of moving from sight to vision.

* * * * * * *

The Countess Dunmore lies back in her bed after an enslaved woman has changed the sheets. The Countess is still weak, though getting better each day. It helps seeing the baby whenever she can, the daughter born this week.

The people who come to the Governor’s House—her husband is Lord Dunmore, governor of the colony of Virginia—are calling the infant “the Virginian.”

Hmmm. Interesting. The term settles into the mind of Lord Dunmore.

The decision to name the baby is, in the Governor-father’s view, a quiet chance to make a political statement. After all, his popularity is sky-high, the result of his recently successful military expedition to the upper Ohio River valley. Can he keep the momentum going? Sure would be nice if he could, allowing him to rise above the struggles bogging down so many of his fellow imperial governors in various clashes with anti-imperial groups up and down the Atlantic Coast.

He looks at his wife, the Countess. He looks at their baby girl.

“Virginia”? Dunmore ponders the name. Let’s marinate it for a few weeks.

* * * * * * *

(so revealing)

Two men, seven weeks.

George Washington and John Adams spent seven weeks in meetings in Philadelphia earlier this fall, at the now-named “Continental” Congress. That’s how they know each other, having never met before then and no longer staying in touch afterward.

(The election making them the first President and first Vice-President under the Constitution is in 1789, fourteen years ahead in measured time, about twelve galaxies and two universes away in lived time.)

Today, 250 years ago, Washington and Adams have utterly no idea what each other is doing.

Adams is writing a letter of remarkable range and depth. His subject is Boston, the colony of Massachusetts, and the imperial crisis threatening to destroy the life known there for the past several generations. He states that he’s encouraged by the public commitment to military training. As many as 15,000 people could mass into an army, predicts Adams. He also says that Americans everywhere—400,000 of them, in his view—are without law and government and yet are trying to fill the gap with inventions of their own design. Some of the inventions are dumb, some sad, some marvelous. He agrees with a critic of the colonial-rights cause that perhaps it would be best for everyone if Massachusetts went its own way. Adams believes that if that happened, the colony would have “Some Sublime Conceptions, which would in that Case have been carried rapidly into Execution.” The Bostonians are “like Zion in Distress: Seneca’s Virtuous Man, Struggling with Adversity.”

George Washington writes a similarly remarkable letter of range and depth. His subject is business, namely, his own, and more namely than that, everything land- or farming-based. His is a dive deep into strategies, actions, and decision-affecting factors that are the inner workings of his economic life. He tracks the truthfulness and honesty of people with whom he conducts trade and commerce in land and agriculture. He knows cattle, horses, and wheat. He monitors gold, silver, and paper currency as they relate to the buying and selling of acreage. In modern parlance, his letter is a business blend of Monopoly, Clue, Game of Thrones, and Call of Duty.

The tips of the two quill pens say so much about each man.

* * * * * * *

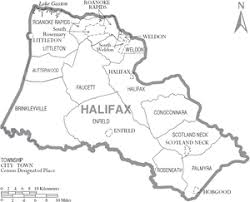

(home county of Miller)

Andrew Miller is in Halifax, colony of North Carolina. He’s had enough, flat-out just plain enough!, of the colonial-rights issue where he lives. He’s doing as much trade as he can before the Association’s wide-ranging economic boycott entrenches. Miller sympathizes with any off-table bargaining that skirts the edges of the boycott. He’s cutting off deals with people whose view of colonial rights include the violation of British laws like the 1763 ban on western land purchases. He states that they’re “enterprising Geniuses in the Land way (who) are certainly of the Quixote kind.” That is Miller’s literary way of saying they’re all insanely unrealistic, dangerously dreamy, and altogether ridiculous in seeking what does not, cannot, and will not exist. Is this the quality of thinking that is driving colonial rights, he wonders. Miller also expects the colony’s imperial governor, Josiah Martin, will soon crack down on speculators who have violated the 1763 ban. Miller hesitates to say much in public against colonial rights because “at these times it may be dangerous.”

* * * * * * *

(newly arrived)

How do you find your place in a new world? How do you get some measure of comfort when everything around you feels mostly alien?

Thomas Paine wonders about the answers to these questions. He’s still seeking his footing in his new world of Philadelphia, having arrived here as an immigrant on the recommendation and endorsement from Benjamin Franklin back in London, England.

Paine finds part of his answer—you do what you love doing. That’s helps you settle in and see a path ahead.

For him, that answer is writing and it often got him into trouble in England. Now, in Philadelphia with its greater wealth, higher rates of literacy, and overall stronger middle- and working-class involvement in politics and political discussions, Paine is writing his first public essay.

It’s a doozy.

Paine being Paine, he’s chosen to tackle the issue that seems obviously central to him in this season of imperial-colonial fury—he’s writing about the horrors of enslavement.

Paine describes in blistering terms the reality of how enslavement happens, from Africa to the Americas. He dissects the pro-enslavement argument that says the Bible permitted the making of Jewish people into slaves. Finally, he calls upon “Americans” to see the clear disconnect between what they’re seeking for themselves as free people and what they’re denying to black people. “But what singular obligations are we under to these injured people!”

A local newspaper publisher accepts Paine’s essay but decides not to print it just yet.

* * * * * * *

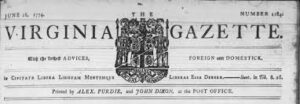

(spreading the word eastward)

Printers Alexander Purdie and John Dixon, partners in operating the Virginia Gazette newspaper, finish laying out the December 10 edition of their publication. One of their articles is an account of the Fort Gower Resolutions debated, written, and endorsed by a group of Virginia officers who served in Dunmore’s military expedition. The Resolutions are the most extensive and significant declaration of what can be called an American military mind (my term) thus far in this season of fury within the British Empire. This unique outlook, comprised of civil-over-military power and a self-identified culture of armed force, has now traveled more than 400 miles east from the upper Ohio River valley to the coastal tidewater of Virginia.

* * * * * * *

(as rendered in a video game)

There’s a man standing in a legislative meeting-space in Annapolis, colony of Maryland, whom a Native tribe in the colony of New York have given a nickname.

They call him “Boiling Water.”

Everyone in the Maryland provincial legislature today, 250 years ago, know him as Charles Lee, a military officer in the British Army who fought in the French and Indian War of 1754-1763. War vet, big nose, loves dogs.

Lee smiles to himself as the men in the room all yell “Aye!!!” in favor of his self-designed military organization bill. It’s now a law, at least as defined by the supporters of colonial rights who have started their own provincial legislature in Maryland during this downward-, outward-, and everywhereward-spiraling imperial crisis.

Colonial-rights supporters will next proceed along lines recommended by Lee, the military consultant: all men between 16 and 50 years of age will collect into militia units, vote for officers in those units, and train at least once every 30 days on loading ammunition they bring into the guns they bring, and learning how to fire and march together.

That’s Boiling Water’s plan for when the boiling water of this crisis spills over the top.

* * * * * * *

(the season of the reason to give)

Where might the real boiling spill and scald? Best guess: Boston. Here’s why, today, 250 years ago.

People of Massachusetts, find it in your heart and your purses to donate money, items, anything to the people of Boston and its neighboring community, Charlestown. Winter is bearing down hard and the British blockade is crushing life in these communities. Suffering and death await them unless we can help them.

People who lead religious congregations in Massachusetts, in addition to reading aloud the call for charitable donations, you must also use your position to urge people in our colony to abide by the rules and regulations outlined in the Association’s economic boycott, recently developed and approved by the Continental Congress.

John Hancock watches from his chair as Speaker of the Massachusetts Provincial Assembly. In flourishing hand, he signs these declarations.

It’s in Boston that tensions and hostile feelings boil hottest. For now, the lid is still on. But the heat beneath continues to burn, and a gurgling, popping, and rattling can be heard within. And the winter blasts its way ahead.

* * * * * * *

(the first installment of what will become a book)

A writer calling him or herself “Massachusettensis” has an essay printed in a Boston newspaper. Ideas in the words contact the spirit in the measures signed by John Hancock. Today, 250 years ago.

Massachusettensis asserts that pro-colonial rights supporters have, in fact, gone up to the edge of treason. The people in Great Britain believe in the fact and purpose of the British Empire. They are as fervently committed to the imperial government as many colonists in Massachusetts are to colonial rights. With each side thus ensconced, a river has been crossed, never to be recrossed back to the former side. The “longer sword” must now decide the outcome.

That sword, Massachusettensis contends, is weak and untempered in colonial hands. Our militia are unreliable, unable to stand against regulars. We are exposed on all sides. And we have no hope of any real support or assistance from anywhere outside New England.

And for what? From what source of ill-treatment? “Will nor posterity be amazed, when they are told that the present distraction took its rise from a three-penny duty on tea, and call it a more unaccountable frenzy, and more disgraceful to the annals of America than that of the witchcraft.”

* * * * * * *

Time can warp.

Also

(the calling he’s talking about)

John Wesley, continuing to refine an approach to Christianity that he’d launched four decades before, writes this today in London, England, 250 years ago:

“It is the Scots only, who when they like a preacher would choose to have him continue with them? Not so; but the English and Irish also, yea, all the inhabitants of the earth. But we know our calling. The Methodists are not to continue in any one place under heaven. We are all called to be itinerants. Those who receive us must receive us as such.”

A few words can express a massive conviction.

* * * * * * *

(one of the most powerful women in the world)

An Archduchess rules a swath of land later called Croatia, Hungary, Austria, and including much of southeastern Europe. She is 57-year old Maria Theresa, of the Habsburg dynasty. This week she has signed a document that calls, first, for education of boys and girls alike and, second, for requiring education for all children between the ages of 5 and 13.

For her part, the Archduchess has given birth to 16 children, 10 of whom lived beyond the age span she now requires for schooling.

* * * * * * *

(no easy hill to climb in Melilla)

Proxy military forces of Spain and Great Britain clash against each other on the northern coast of Morocco, at the port town of Melilla on Cape Three Forks of the Mediterranean Sea. A siege begins. British authorities support Mohammed ben Abdallah, the Sultan of Morocco, in his attack on the Spanish-aided community.

Nation. Empire. War. Along the waters separating the two continents of Africa and Europe.

For You Now

Virginia Dare, the first English baby born in the colony called Roanoke. Virginia…Dunmore. Like the sound of it?

Maybe the Governor-Father is looking back at the one and thinking forward about the other. Might make sense, perhaps.

Boiling Water Lee has a solid military record from the prior war and, in the eyes of the Maryland Provincial Assembly, appears a knowledgeable consultant if a next war happens. Solid enough move, if we don’t think about it too long.

Washington and Adams, prominent names in the colonial-rights movement in fall 1774 that will become still more prominent as time goes on and a nation is born. And then POTUS and VPOTUS in spring 1789. Seems a likely fit until you start to know things.

And don’t forget the weirdly-named essayist. Massachusettensis suggests this whole thing is as bad as the hideous witch experience of Salem. Gulp, if it’s true we’re all dead.

Just be careful. Time warps, especially as a lens. In fact, I suggest you build in a beat—before you assert in the present that past’s Thing Two looks like a nice straight line from past’s Thing One, count off one or two or three and seek more knowledge of life in between them. And the more the life between, the more beats you’ll need.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: have I got a Thing Two-from-Thing-One about America that I’m assuming holds up without double-checking?