Americanism Redux

July 4, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

(a juncture from AI)

In the future, there is a juncture. You believe this, and so do I.

At the juncture, everything, or nearly everything, of today that is important, contested, and unresolved will meet. A, B, C, D, and a dozen others will come together. Plans, actions, events, trends, people, resources, the animate, the inanimate, the above, the below, from these and other sources, a great combining, connecting, clashing, colliding will occur. At the juncture.

And out of it, beyond the smoke and past the horizon, the hope is for a positive emerging from, and after, the juncture. And your expectation—is that the same as your hope? Likely not, as the negatives are too disturbing for the dwelling.

Even so, there’s trouble in your mind. You hear sounds without words. You see bodies without faces. At the juncture.

Today, this day, you do your life. Summer is a trumpet in early July. The echo bounces off the trees where this week the wood is alive and bending. Some time later, in the juncture, the green turns tinder, the pre-life of gone life, then new life.

* * * * * * *

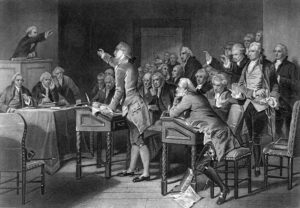

Robert Smith and Thomas Procter are friends and respected colleagues. They know wood, what it can do and what it can become. Residents in Philadelphia, colony of Pennsylvania, regard them as two of the town’s “master carpenters”; Smith has even designed, built, and finished “Carpenters Hall”, one of the town’s most beautiful and well-known buildings, a remarkable statement for a community noted for elegant structures. This hall is where the Carpenters Guild meets on a regular basis. The Guild’s members are leaders of the town’s thriving middle-class, people earning good incomes without much of an inheritance, who care about the community, who work hard while extending helping hands to those around them. Select what you want—Smith and Procter, the Carpenters Guild, the Carpenters Hall—and you’ll have a leafy symbol of Philadelphia’s healthy self-government.

Which is why Charles Thomson, one of the most vocal and insightful leaders of Philadelphia’s pro-colonial rights movement, is maneuvering to have Carpenters Hall selected as the location for the upcoming “general congress” at the juncture ahead in the imperial-colonial crisis.

Thomson knows it sends a signal, both to those outside the hall and those who will meet inside the hall.

Thus far, by today, July 4, nine colonies have agreed to send delegates to Philadelphia for the general congress set for late summer, potentially in Carpenters Hall that Master Carpenter Smith built.

* * * * * * *

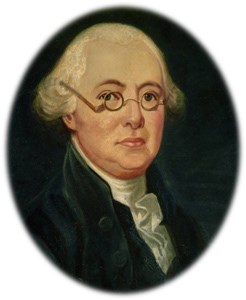

(an older James Wilson)

Okay, it’s time. Now, after six years, it’s time. Tell the printer to go ahead. Tell him to: …grab the ink bulbs and pat the blocked letters onto the page and…pull the devil’s tail to press everything down. Page by page, copy by copy.

James Wilson, also of Philadelphia by way of Scotland, 31 years old, approves the printing and distribution of a small book he wrote six years ago, in 1768. He’s dusting it off, bringing it out, putting it forth from the world of his mid-20s to the world now, in his early 30s. Yes, seems a long time ago—the town of Boston was boiling mad, the first posting of British Redcoats, wild ideas flying around about about imperial brutes and colonial thugs. Uh. Hold on. Is it really so different?

Wilson thinks yes, it is.

His writing was entitled in 1768 “Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament.” He’s keeping the title today, in 1774’s issuance, because he thinks his ideas will meet the needs of the late summer’s “general congress”. Wilson believes the point he made six years ago must be embraced in 1774: that the core thread of the colonial tie to England is the King, not Parliament. And yes, George III’s approval is on the Boston Port Act, but it’s Parliament that conceived, designed, and passed the “Coercive Acts” of this spring and summer. Cut ties to the Parliament, keep ties to the King, solve a relationship for a new age of empire.

When the juncture arrives, Wilson wants the blame placed where he believes it belongs. On Parliament.

* * * * * * *

(like a Pickler)

Henry Pickler wears his Red Coat on Boston Common. He’s a private in the British 43rd Regiment of Foot, an infantry unit. From orders and commands far above him on the organizational chart, he traveled west across the Atlantic Ocean with the 43rd. He landed in Boston as part of the force to enforce, in this case, the shutting down and sealing up of the port of Boston, in punishment for the tea protests back six months ago. For the past few weeks Pickler has struggled to adapt to his new assignment.

Pickler feels the hatred in the Common air. When he wants to buy food from a local vendor, he gets nothing but scowling looks. When he needs a repair to his uniform or shoes, he gets nothing but glares and mumbled curses. When he is off-duty and walks the cobblestone streets to relax, he gets nothing but turned backs and cold shoulders.

A British regimental officer explains it: “The people are very troublesome here (in Boston), but won’t meddle with us openly, which is the sincere wish of us all, that we might get the business over, for we are kept in suspense, harassed, and fatigued, without any prospect of having the business settled.”

Pickler and his comrades want to “settle it” once and for all. Let’s have the “meddle”, the fight, get it done, wipe the table clean for the reset.

Further up the chain, General Thomas Gage, newly installed military governor of the colony of Massachusetts and Pickler’s highest ranking commander on American soil, looks around and sees this: Boston’s mobs make the rules and enforce the rules here, a condition that “by Time (has) acquired a Firmness that I fear is not to be annihilated at once, nor by ordinary Methods.”

So what is Gage saying? Is a “meddle” an “ordinary Method” or not? What’s a Pickler to do?

The answers are out there, at the juncture.

* * * * * * *

The reactions of many colonists around Pickler and Gage is the result of planned action. Today, July 4, 250 years ago, this sort of planned action is in various stages of implementation across scores of communities in the British colonies.

People angrily opposed to the Boston Port Act and other of the Coercive Acts are identifying residents supportive of imperial power and willing to undermine any resistance to imperial authority. These imperial sympathizers are being named. After naming, the next step is physical and mental intimidation, rather like that shown toward Private Pickler. The aim is to wear down the sympathizer into acceptance of the pro-colonial rights stance, or to drive them out.

To label them as mobs, as Gage has done, is to discount their ability to organize, to plan, to execute, and maybe most of all, to adjust at the juncture.

And almost every community has something like this, whether for Redcoats like Pickler or imperial supporters…

* * * * * * *

(not on Adams’s list)

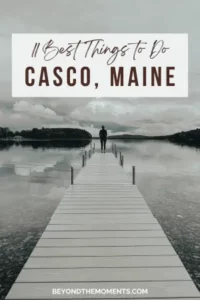

…like Jonathan Sewall, who lives in Casco, in the far northern portion of the colony of Massachusetts (now Maine).

Today, 250 years ago, John Adams is in a carriage rumbling his way north toward Casco and Sewall. Adams and Sewall are close friends. Adams know he’ll be seeing Sewall in a week or so. Adams is “riding circuit”, meaning he is traveling to serve as attorney in court proceedings at various northern towns up the Atlantic Coast from Boston.

Adams hates these duties. They give him all too much of a chance during the travel to sink into his own thoughts about his lack of success, lack of standing, lack of stature.

But today, what he hates more than anything is the conversation he’ll likely have to have with his friend in Casco. Sewall is a die-hard supporter of imperial power, authority, and custom, a “Loyalist” through and through. Adams dreads their exchange, knowing as he does that he and Sewall are as opposite as they can possibly be regarding the Boston Port Act, the Coercive Acts, the tension-turned-crisis-verging-on-catastrophe state of imperial-colonial reality. Will Adams find any sliver of common ground with his friend?

It’s a juncture that John Adams knows is coming.

* * * * * * *

(Bryan Fairfax)

Bryan Fairfax reads a letter from a friend of his deceased father. Fairfax is in, yes, Fairfax County, colony of Virginia, which shows the influence of the family name in this area. Fairfax the younger wants to win election to the colony’s Assembly, or legislature, in an election that Governor Dunmore slated for several days from today, July 4.

Fairfax has attempted to explain to his deceased father’s friend his frustrations of trying to seek votes as a moderate candidate. The condition, it seems to Fairfax, doesn’t allow for cautious, prudent statements and policies. Can’t we pin our hopes for overturning the Boston Port Act on another formal appeal to British imperial authorities? To their reason and good graces? These are the questions that Fairfax asks, the positions that Fairfax wants to take, if elected.

If his deceased father’s friend has any say in the election outcome, Fairfax will, and should, lose. George Washington knew the elder Fairfax and for a while as a younger, up-and-coming man wanted to emulate William Fairfax, Bryan’s father. Washington responds to Bryan Fairfax today, 250 years ago, with an outburst that can almost be felt from the parchment it’s written on. Washington is incredulous that Fairfax still has faith in written appeals to the British government. Washington believes the time has come for punching back through collective action. The “general congress” should prepare the blow.

For now, at the juncture, the boxing ring is empty.

* * * * * * *

(one of the virtues)

“A Planter”, perhaps someone known to Washington and Fairfax, tells the reading public in the colony of Maryland that the “present fashionable toast is ‘liberty and property’, and a good toast it is, however, it ought not to go before, but ought to follow what liberty and property depend upon, industry and frugality.”

To talk about following in the future is to project a juncture.

* * * * * * *

These paths run apart though parallel in July’s long and wide daylight. Under the blinding sun, however, a slight convergence is in play, when the spaces shrink, as the gaps narrow and tighten. As darkness arrives sooner, a first touching will begin when the juncture is here. But not today.

Also

(Rokeby)

61-year old Matthew Robinson-Morris is about as eccentric as you can get.

A former member of Parliament from Kent in England, he’s opposed to fire, drinks gallons of beef-tea along with buckets of water, and wears a beard so long and thick and broad that you can see it when you stand behind him. He’s also known as Lord Rokeby.

Rokeby has kept a strong interest in public affairs. He counts himself a strong advocate of the British colonies, a “tried and true Whig” who believes in limited government, the elected legislature’s supremacy over the king and executive, and individual rights.

He’s the recent writer of a pamphlet and essay that so popular that colonial bookshops and booksellers can’t keep up with the sales. It’s his “Considerations on the Measures Carrying On with Respect to the British Colonies in North America”. He has had multiple printings already to satisfy reader demand. Rokeby uses plain, straightforward language to build his argument that British Prime Minister Lord North’s ridiculous policies had created the existing crisis. Listen to the colonists, Rokeby advised, and act on their concerns.

Agree with Rokeby and he’s a daring truth-teller. Disagree with Rokeby and he’s a raving lunatic. Maybe the juncture will sort it all out.

For You Now

The juncture isn’t now, there’s no question about that. If it was, if today, you’d know it. The telling would be obvious.

So today has the moments you expected and a few you didn’t. Today might also have had moments that suggest the juncture is moving closer. Perhaps you can see a bit more clearly the things you believe will be involved in the juncture at its later date. If so, you’ll be watching closely as the paths and trails unfold ahead, tracing toward the juncture. You’ll be all the more startled, as if from nowhere, a new track appears to become part of the juncture.

I’ll wager that you might think of the Declaration of Independence as the juncture for people in 1774. Not really. Their juncture, for those who are immersed in it, is about two or three months ahead, to the proposed “general congress”. The Declaration is still a couple of years away.

The point I’m making is that in real-time, in a person’s present, the juncture looks different than it does in hindsight.

Now, with you immersed in your today, how best to link to the juncture?

Awareness and patience can help. If you keep aware of the world around you today, your chances grow of recognizing at least one connection significant to the future time of togethering. Follow the example of Gage here with his understanding of new conditions on the ground.

Don’t assume that when you see one connection you must see more just as quickly. Impatience will drive you to cram additional key points into the wrong mold. Hold off for a brief spell—let the points you think you’ve discovered come to a fuller state, and then see if any of them constitute the next connection. The time that Adams had in his carriage gave him the chance to filter this thoughts and emotions on the upcoming talk with Sewall. A conversation had instantly would have involved bigger risks of impulsiveness and vindictiveness, of ties burned more than broken. Patience is a magnifier, bringing an abundance of other advantages.

When a juncture includes an event with new possibilities, use your creativity and imagination to anticipate unusual outcomes and effects. Thomson’s perception of Carpenters Hall illustrates such a step, as does Washington’s rejection of Fairfax’s stalled action and Wilson’s re-ignition of his original written work.

Finally, understand that a element of inexorability is afoot. That’s not determinism, that’s not fate or fate-ism, that’s not the killing of individual choice. I’m referring to the reality of a juncture where a) the distance between things reduces at the same time that b) the overall number of things that might be reduced is diminishing. By the time of the juncture (we’ll call that c)), these once-numerous-now-superfluous things will have worn, fallen, or faded away.

Only the juncture is left.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: what one thing from today do you think will almost certainly still exist when, in the future, a juncture occurs with other significant things?

(Your River)