Americanism Redux

September 5, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

(this is the Pepperell flag, perhaps for American Moment holiday)

America, listen to me. Start a new celebration, commemoration, memorialization. Add it to the 4th of July.

Do it across the first five days of every September. Beer and barbecue, wine and quiche, makes no difference to me. It does make a difference which flag you fly. It’s shown here. Go back to last week’s Redux to understand why.

Use this set of days to honor the true shining moment of you, of us.

The shining Moment of America, a few special days in early September 1774.

* * * * * * *

The people who’ve known him since childhood will tell you all about it. He’s remarkable—intelligent, thoughtful, caring of others, willing to help whenever needed. By now, at age 20, he’s still the same but with the added gifts that a life lived well has brought to him—he has taught himself to work with iron, chisel and lay stone, process grain into flour and really “is capable of doing almost any Sort of Business.” Even the way he walks draws people’s attention—confident, casual, engaging. With all of these talents and attributes, he’s “in the character of a Freeman.”

Billy, or Will, they call him. “Freeman” might be the name he likes the most.

He’s out and living and alive, a one-man American Revolution answering to no king and no enslaver—including the one chasing him who’s paying money for his capture—somewhere along the valley of James River in the colony of Virginia, his future born around the same time as the baby Liberty in the town of Pepperell, colony of Massachusetts (see last week’s Redux).

I wish I could have known Billy/Will.

* * * * * * *

(where Isaac Bee learned)

Maybe, in the woods, Billy/Will encounters another American Revolutionary, Isaac Bee, graduate of the Bray School for black children in Williamsburg, colony of Virginia. Bee is 19 years old and “thinks he has a Right to his Freedom because his Father was a Freeman, and…will endeavor to pass for one”. This Bray grad excels at reading and writing and if he feels safe enough to have a campfire at night, you might find him reading a copy of the latest essay by Phocion.

* * * * * * *

(modern version of who is to be warned against)

“Phocion” is another one of those adopted pen names. Taken from ancient Greece, he was “The Good” in those days, a deep believer in modest living, good soldiering, and reputed to be the most honest member of the Athenian Assembly.

Fast forward to the moment of Freeman and Bee in the Virginia woods, and you might see them reading a newspaper with essays written by a 1774-writer who writes as “Phocion” to say that the real problem in the imperial-colonial crisis is the king and all things kingly. In addition, Phocion states, ” ‘Tis truly amazing to reflect on the late revolution of American liberty; a revolution which man not long be doomed to stand alone, for fate seems big with the change of empire.”

In the eyes of Phocion, between stars above and campfires below, the world might just be catching on.

* * * * * * *

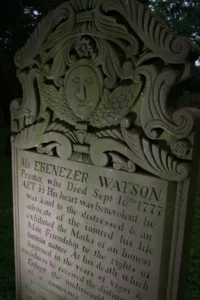

(the publisher’s grave)

Ebenezer Watson publishes the “Connecticut Courant” newspaper and today, 250 years ago he’s in a hurry to find as many books about the current imperial-colonial moment as he can for advertising in the Courant. As of today, the day before printing the latest edition, he’s got multiple printings of four different “crisis” books to sell to subscribers. Chances are good that they’ll be snapped up by eager readers. People can’t get enough of crisis these days.

* * * * * * *

(the astute John Penn)

A descendant of the founding family of Pennsylvania—Penn-named, if you will—John Penn is the current lieutenant governor of the colony today, 250 years ago. He is smart, insightful, a sharp observer. Penn is a reliable source for understanding current events.

Here’s his latest thinking on September 5’s opening morning of the special congress meeting in Philadelphia: “From the best intelligence that I have been able to procure, the resolution of opposing the Boston (Coercive) Acts, and the Parliamentary power of raising taxes in American for the purpose of raising a revenue, is, in a great measure, univeral throughout the Colonies, and possesses all ranks and conditions of people…general, however, as the resolution is to oppose, there is great diversity of opinions as to the proper modes of opposition.”

Re-read Penn’s analysis. He’s in the American Moment.

* * * * * * *

(Cadwallader Colden)

Penn’s imperial political office-holding counterpart in the colony of New York is Cadwallader Colden. Colden’s view is a bit different. Colden believes the worst days of violence and intimidation are over and that “the populace are now directed by men of different principles, and who have much at stake.” They are propertied, he says, and not prone to “burning of effigies or putting cut-throat papers under people’s doors.”

Still, a parting thought seizes Colden’s mind: “I hope I am not deceived in thinking that the people of this Province (New York) will cautiously avoid giving any new offense to the Parliament, but great numbers are so fluctuating, that some unexpected incident may produce bad effects.”

Great numbers fluctuating, in the American Moment.

* * * * * * *

(across this land)

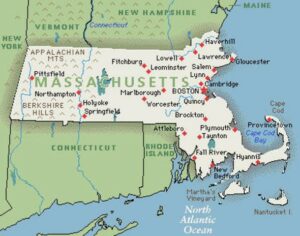

East of Colden’s New York, in the colony of Massachusetts, the same gnawing fear races from village to village. Rumors fly that British General Gage is about to launch a military operation with Redcoat units. Reports call for the colony and surrounding areas to organize a 40,000 to 50,000-man military force to counteract Gage and defend colonial rights.

* * * * * * *

(Oliver house)

Seriously? How would you find that many volunteers? Here’s a real place to start right now: the house of Judge Thomas Oliver in Cambridge, colony of Massachusetts. He and his family are staring out the windows of their home and see, by the judge’s estimation, somewhere between 3000 and 4000 people, with one of every four carrying a sword, a hatchet, a club, a musket, or a rifle. Oliver’s wife and children are emotionally unraveling, like you’d expect—screaming, crying, tremoring, praying, slinging to one another while reaching for him and begging that he signs the paper that’s been carried to their home’s front door by a group of five “Committee” men. The paper is a declaration of resignation from the Council of Mandamus that British Redcoat General and Governor Thomas Gage has dictated, illegally in the opinion of the thousands.

In a mixture of rage and terror, debating with himself and trying to calm down his melting-down family, Oliver finally scratches his signature on the parchment document. From somewhere inside himself he notes “that in justice to them, observe, that, during the whole transaction, they had never invaded my enclosures.”

The crowd, the mob, the assemblage, the potential pool of armed volunteers—pick your term—breaks up and leaves the yard surrounding the judge’s “enclosures”.

20 of the 36 Gage-selected Mandamus Councilors have now resigned. It’s the American Moment.

* * * * * * *

(much like the men he’ll be guiding)

Matthew Arbuckle sits at Camp Union near the Greenbriar River. Around him are cattle, horses, wagons, barrels, tents, and hundreds of men. The smoke drifts through the air. Campfires.

Arbuckle is a “captain” in the volunteer force of men raised by Colonel Andrew Lewis and authorized by the British imperial governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore.

Arbuckle is the first white man to have hiked the full length of the 100-mile long Kanawha River valley, hiked and survived, that is. No one among the Virginians knows this land as well as he does. That’s why he’s received the honor of serving as chief scout, guide, and vanguard officer for the 500 volunteers who leave tomorrow to invade Shawnee lands in the Ohio River valley. It’s part of Lord Dunmore’s drive to seize the land in the King’s name, the colony’s name, and the governor’s name.

In his own private war, for a purpose that only he knows, facing west.

* * * * * * *

(where the waters divide)

The Appalachian Mountains divide where the waters flow. East they rush toward the Atlantic Ocean where the latest empire teeters on the brink of implosion. West they roll toward the Gulf of Mexico through empires gone, old, and new alike.

The River of the American Moment.

Also

(the subject of talks)

Two British political commentators in London write letters for friends in America. They inform them that the British government is in talks with General Jeffery Amherst about leading a contingent of Redcoats across the Atlantic to America. Similar discussions are underway to engage both European and Native American military support to fight American protestors.

The commentators urge protestor-colonists to take a three-part approach: 1) unanimity is your greatest strength; 2) show a willingness to repay the British East India Company for lost property, meaning, tea from last December; and 3) stay silent when it comes to harsh criticism of the British government.

Follow this tripartite strategy, Americans, and you’ll get out of this current crisis in the current moment.

* * * * * * *

(their leader)

A small group of Spanish settlers led by Antonio Gil Ibarvo offers thanks to God on the banks of the Trinity River, today, 250 years ago. They have a new town called Nuestra Senora del Pilar de Bucareli. In a few days they’ll begin building wooden houses around a planned plaza and church. Spanish imperial officials in San Antonio de Bejar have granted them a ten-year exemption from taxation.

* * * * * * *

(the baby’s future handiwork)

Today, a baby cries in Toulouse, France. Growing into childhood, Charles Brocas will show a talent for drawing. His most famous painting will be:

“The Death of Phocion”

(viewable in 2024 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin)

For You Now

(let’s add one for the first five days of September)

Abraham Lincoln said in a speech that he’d researched and studied it and had decided that the American nation’s true founding was in 1774 with the outcome of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

A long-forgotten historian from the 20th century with the perfect name of Page Smith (yes, Page!) wrote that the year 1774 was the “purest” of the entire American Revolutionary period because war had not yet brought its tragedies and trade-offs.

I’m standing on the shoulders of Lincoln and Smith to offer an even tighter spin on things—the first five days of September 1774 comprise the American Moment.

Here’s what I mean.

It’s September 1-5, 1774 and almost everyone in the colonial world is talking, debating, contemplating, reading, or writing about rights, liberties, the roots of both, the loss of each, the state of nature, the rise of government, and on and on in political philosophy. See the door to a tavern or church or shop? Go inside and you’ll immediately find yourself immersed in politics, political thought, political action, all wrapped around self-government.

They’re also looking back for lessons and insights from ten years ago and the Stamp Act furor, a hundred years ago and the Glorious Revolution, a half-millennium, a full millennium, and longer ago from Magna Carta and Rome, Greece, and Judea. Phocion is back.

Nearly everything about governing ourselves is on the table, from options to possibilities, including for a surprisingly vibrant fraction of the populace the end of enslavement. There’s a rise in the use of the word “freedom” in ads seeking the capture of men, women, and children fleeing forced-labor conditions or bondage. Ask Issac Bee, or Billy/Will Freeman.

People express themselves as individuals and in groups, apart and in community. There are the religiously devout, the skeptical, and the unbelievers. Men, women, children. One race, bi-racial, multi-racial.

They’re emerging from homes and docks for meetings and gatherings. They’re hearing listening to speech-makers and resolutions read aloud, voting on final drafts, and choosing representatives for larger conventions.

And speaking of larger conventions, thousands of people are looking to the delegates starting their work today in Philadelphia. They trust them. They have faith in them. They are relying on the special congress to change the empire and the imperial status quo.

In small groups, the congress’s delegates travel from town to town on their way to Philadelphia. At each stop they’re greeted with cheers, clasped hands, words of hope and encouragement. We’re counting on you and we know you can do it.

The back-biting hasn’t begun. The lies haven’t started. The broken promises and double-dealings are yet to happen. The naked self-interests are concealed. Jealousies, rivalries, and betrayals are out of sight. Better angels are center-stage and bitter demons shoved to the wings. Politics and parties don’t seem to exist in these first five days.

Yes, some violence has occurred, as have threats and vengeance. The Olivers will tell you that. But overall, bloodshed is absent. The Olivers will tell you that, too. Fighting and war-making are in the distance, across the Atlantic or the Appalachians.

For these few days in early September, a raw idea of self-government glows in the fire. In the time ahead, it will be removed, hammered, plunged into water, and extracted hissing and steaming. Fired, pounded, cooled. Over and over and over again.

We’re doing that still.

I ask you to pause in our times. Stand back, wipe your brow, and remember to smile through the sweat. Celebrate, commemorate, and memorialize the American Moment of September’s first five days.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider—what lesson should we take from the first five days of September 1774?

(a forge on the river)