Americanism Redux

September 26, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

An American original.

Living a life in a place, and a place that shapes the living of a life.

But the life needs birthing and the place needs making.

* * * * * * *

(beginning)

Elizabeth lays back in her bed. The sheets are soaked in sweat and linen cloth shows traces of blood. The blankets have spots of dampness from water spilled out of pots and cups. Exhausted, aching, and weakened, she has a loving look on her tired face. Next to the bed, Nathan reaches to hold the hand of his wife as she holds the living body of their son.

Today, 250 years ago, Elizabeth and Nathan name their son “John”.

Some of John is yet to be known through genes passed on by John’s parents. Some of John is already known by what’s happened during Elizabeth’s pregnancy. Some of John will be known through the environment of his family upbringing and daily surroundings. And finally, some of John will be utterly unknown and left up to him as to what and how and why he sketches in the unfilled spaces. All together, these are the some of John’s parts.

Linger a moment on the latter-some, the unfilled spaces. How much of them will be affected by the nature of the wider places around him, the town of Leominster, the county of Worcester, the colony of Massachusetts, the region of New England, the coast of British America? Each of these five will have their own motions and stresses, not much different from Elizabeth’s womb.

When everything is finished and we come to know the whole of John, what can we say will have had the strongest effect, the deepest imprint, the longest reach?

In his life John, born a colonist into a family of Yorkshire immigrants, will mature as an American and, like some of his nation, will move west, become a Christian missionary, and embrace a passion over possessions. He will be optimistic, generous, friendly, and restless. He will travel and be remembered wherever he travels for the seeds he plants, the nurseries he tends, the orchards he establishes. John became “Johnny” and Chapman became “Appleseed”.

But first, 250 years ago today, he is born.

* * * * * * *

(the Guards)

All of 14 years old—practically an elder statesman compared to baby John Chapman—Wanton Casey lives in the county of Kent, colony of Rhode Island. He’s excited today about the news of a local group now calling itself the “Kentish Guards.” Approximately thirty men of Kent County have decided to form into a military unit for preventing “the boats from the British fleet from getting into the harbor.” They have muskets, gunpowder, bullets, and insignia for their clothing. Within hours, Wanton Casey will join the Kentish Guards.

The Guards are a unit of volunteers acting on their own authority and legality. They carry on a tradition of unpaid, part-time, civilian-oriented, and town-based militia that has existed across the colonies for more than a century. But in their creation at this specific moment, they have no formal approval by the colony’s elected legislature. The plan is to seek such approval as soon as possible. In the interim, the Guards hold together in relationship to each other, and to the cause of colonial rights around which they have bonded.

* * * * * * *

(in Rye)

There are 63 people in Rye, County of Westchester, colony of New York who embody everything the Kentish Guards have vowed to each other to oppose.

The Rye folks are fed up:

“We the subscribers, Freeholders, and Inhabitants of the town of Rye, in the county of Westchester, being much concerned with the unhappy situation of public affairs, think it our duty to our king and country, that we have not been concerned in any resolutions entered into, or measures taken, with regard to disputes at present subsisting with the mother country. We also testify our dislike to many hot and furious proceedings in consequence to said dispute, which we think are more likely to ruin this once happy country, than remove grievances, if any there are. We also declare our great desire and full resolution to live and die peaceable subjects to our gracious Sovereign George the Third and his laws.”

We…declare…our…dependence.

63 signatures appear on the bottom of the document.

* * * * * * *

(John Bradstreet)

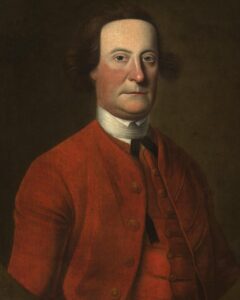

The Major-General is dead.

In New York City, John Bradstreet has died at age 59. He was a unique man, born Jean-Baptiste Bradstreet in the British colony of Nova Scotia. During more than thirty years in the British Army as a fully-employed professional soldier—a member of a “standing army”—Bradstreet had achieved the difficult balance of serving as a British Redcoat officer while retaining a workable relationship with British colonists who fought alongside him. He understood the need to adapt British methods to reflect American terrain and American skills, including the hard-to-find combination of canoeing, tracking, carpentry, and hand-to-hand fighting. (Bradstreet’s “bateaumen” would be forerunners of the men who transported George Washington’s beleaguered force across the Delaware River in late 1776.)

Bradstreet knew the ambitions of the colonists, recognized the presence and influence of the Natives, and navigated the backrooms and by-ways of imperial policy. Bradstreet possessed a voice and experience that are undeniably vital and increasingly missing in these days of crisis. He had bled on the soil and in the water.

Today, Redcoated pallbearers carry his coffin into Trinity Church in New York City.

* * * * * * *

(John Johnson)

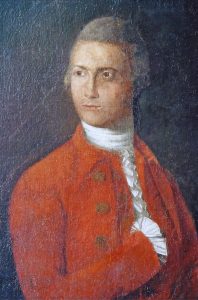

John Johnson, son of a man who was rival to John Bradstreet, sits at Johnson Hall in Johnstown, colony of New York.

That’s a lot of Johns in the span of person, building, and community, and you know what that means—influence.

John still thinks about his father, Baronet William Johnson, who had died a few months ago. William Johnson had amassed a fortune in land, currency, and political prestige as the dominant British imperial figure in the central and western regions of the colony of New York. His specialty was an unmatched ability to interact with Native tribes and leaders and political dynamics. He translated that ability into money and power and, of course, his baronetcy as Sir William.

John Johnson had inherited his father’s wealth and his father’s position. It is unknown if John Johnson has inherited his father’s skills in relationships with Native Americans.

John waits today for his first major conference with various Native leaders and tribes from the eastern Great Lakes and upper Ohio River valley. They’re traveling by horse, by canoe, by foot toward Johnson Hall. Among the travelers are many older Native leaders who remember Sir William and wonder about young John.

Beneath the altar at the Episcopal Church in Johnstown, the body of the baron rests.

* * * * * * *

(cooling)

You pick up a copy of today’s edition of Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser. Feels a little heftier than you’d expect. Ah, that explains it—it’s six pages today. A lot of news and stuff to print.

A glance at the front page. Done. You open it up to the inside pages. Page two, okay, a quick sip of coffee.

Now on to page three…hold up…what’s this?

Two short articles, one immediately next to the other.

The first is by “A Pennsylvanian.” The writer warns you that the coming election for the colony’s legislature may be the most important in our lives, maybe the most important ever in the history of the American colonies. Next year, 1775, will be a year unlike any other. We’ve got to choose our representatives carefully. We need to hand them temporary authority thoughtfully. We’re surrounded by enemies on all sides. We’ve got to protect the privileges passed to us by our ancestors and find a way to cut through the noise and dust to hear the cries of our unborn children and their children’s children.

Whew. This is truly a remarkable time to be alive.

And then the second article.

It’s “A Short Story”, unsigned and unattributed, about a Virginia enslaver with a defiant slave named Jack. Jack made friends with people who told him his enslaver was evil. Jack listened and decided they were right. He began a plan to train a dog to attack and kill his enslaver. The enslaver asked for advice from friends of his own, who told him to tell Jack that he would be deprived of food and clothes and whipped until the edge of death. Jack listened and decided his enslaver would punish him exactly as he threatened to do. Jack went back to work and, the writer asserts, “became the best servant in the province.”

Whoa. This is truly a difficult world for living.

You put down the newspaper and stare ahead for a few seconds. The coffee has cooled and bitter to the taste. Shove it aside and move on to the day of work ahead.

* * * * * * *

(they’ve given it up)

It’s about the cup of tea, right?

That’s what a small community of pacifist Quakers in Maryland are asking. They hope for an answer of “yes”, as they have stopped using tea in their homes, a signal of solidarity with the protests. But it feels as if events are passing them by. Aggression is growing among their non-Quaker neighbors who despise British policies. The demands for colonial rights first came with calls for a tea boycott, then an economic boycott, and then for punishment of all boycott violators. Many Quakers near Annapolis are nervous that the protests are sprinting toward raw violence and open warfare.

The gun has fired, the race has started, and the Quakers are still standing at the anti-tea starting line, waving their empty cups.

* * * * * * *

(where they’re working)

The special congress is in its third week of meeting at Philadelphia. Delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies attend. Their task, of course, is to define a colonial response to the Coercive Acts enacted by Parliament and with approval from King George III. Having absorbed the untrue rumor of violence by the Redcoats in Boston and the arrival of the radical Suffolk County (Massachusetts) Resolves, the delegates have reached a temporary outcome of sorts.

Delegates agree that “merchants and others” should be asked not to send new orders for goods and items to their counterparts in England, and at the same time they should delay fulfilling orders already made and ready for shipment to England. In addition, the pair of requests should continue “until the sense of the congress on the means to be taken for the preservation of the liberties of America.”

More work seems to be ahead for the delegates in Philadelphia in further decoding “the means to be taken”.

* * * * * * *

The pangs of birth.

Also

(modern Cadiz)

Lumber—there’s too much of it, so prices have dropped. Codfish—bad fishing so far, looks like the supply is low, which means if demand is there, the price will go up. Same thing but even more so for various grains—farmers had a poor growing season in France and Italy, translating into skyrocketing prices for the staples of cooking and eating, such as wheat, Indian corn, and kidney beans. This is the latest market information gathered and presented by the business partnership of Bewicks, Timerman, and Romero in Cadiz, Spain. They’ve written it all down in a letter addressed to Aaron Lopez in Newport, colony of Rhode Island. Lopez will receive the information in about six weeks. He’ll have to start looking frantically for any wheat, Indian corn, and kidney beans he can find. Prices, like profits, can change.

* * * * * * *

(Adam Smith)

Adam Smith is in Kirkaldy, Scotland, writing his second book, with a shortened title of “The Wealth of Nations”. He writes:

“The real price of every thing, what every thing really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and the trouble of acquiring it. What every thing is really worth to the man who has acquired it and who wants to dispose of it, or exchange it for something else, is the toil and trouble which it can save to himself, and which it can impose upon other people. What is bought with money, or with goods, is purchased by labor, as much as what we acquire by the toil of our own body. That money, or those goods, indeed, save us this toil.”

Gotta get them beans.

For You Now

(“objects may appear…”)

You look back and things seem so clear. It’s the value and the danger of hindsight.

Elizabeth gives birth to John, and the delegates in Philadelphia are in the midst of their own birthing process of a new nation. That’s how simple and obvious it looks to us now, 250 years later.

You and I know it’s the complete opposite of that, or at least we should. We know it from our own lives where the present’s link to the future is anything but clear and the present’s tie to the past is often mysterious. That’s intuitive. And yet we somehow lose our grip on this truth whenever we glance backward into time, into the past. The view in the mirror seems so clear.

This is one of my primary motivators for doing Americanism Redux.

Look at the rest of the story of this day and week 250 years ago. The truth of life’s chaos and complexity, of the hundreds of small things with large meaning and vast potential, is everywhere. You see it in Wanton Casey, in the Rye Declaration of Dependence, in the twin burials of two imperial figures, in the invisible thread that runs from the writing desk of Adam Smith in Kilkaldy to the mercantile house of Bewicks, Timerman, and Romero in Cadiz to the meeting tables of delegates in Philadelphia where a collective economic boycott is under debate.

That isn’t just a River you see. That is the swirling set of trillions of drops of water amalgamated together into a moving, molding, and often rushing force.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: how much of your life is a reflection of a place?

(Your River)