Americanism Redux

September 19, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

(the green hints of first)

A campfire brings a rare feeling in the early fall.

Before frost and cold and icy breath, a fire of early fall is for warmth, not heat; for whispers and spoken words, not shouts and wild tirades; for support, not survival.

Next to a fire of early fall, you cover your arms, you wear a hat against the chill, you wrap fingers around a mug and sip a soothing drink. The coats and the gloves are for later.

Tilt your head slightly downward, set your eyes on the burning wood. Drawn by reddish-orange flames and whitish-orange embers, you’ll follow your thoughts. They’ll drift to a different place.

By the fire of early fall.

* * * * * * *

(Fithian)

This first fire of early fall is a “fine Fire”, observes Philip Vickers Fithian, the 27-year old teacher working as a live-at-home teacher on the plantation of Robert Carter III in the colony of Virginia. Fithian savors the moment as this “fire looks and feels most welcome.” He laments the effect of the fire on the Carter children. Both teacher and students react to it, but they are “garrulous and noisy.”

Regardless, Fithian absorbs the warmth, the glow, the aroma. The fire’s effect helps him think less about an illness that’s been hounding him.

Improving in these minutes before the fire of early fall, Fithian lets himself drift into thought. His thoughts bend first toward recollection. They bend back toward remembrance. Watching wood become coals and flames become smoke, he replays in his head the months at the College of New Jersey. Suddenly, the whole picture straightens out and makes perfect sense—the studying, the meals, the lectures, the practical jokes, the people, the parties and goofing-off. Fithian sees experiences melding to memory and time yielding riches. What a glorious time it was, he thinks.

The moon of this month is Harvest and Philip Vickers Fithian gathers the bounty of a season. Next to the fire of early fall.

* * * * * * *

(Kirkland)

Today, 250 years ago, Samuel Kirkland walks beside the fires and smoke of Oneida in west-central New York. He doesn’t know it yet but money is coming his way. He’s getting compensated for his work in finishing the construction of a small church.

Kirkland is a Christian minister and John Hancock, the Boston merchant so active in the colonial protest movement, is collaborating with Harvard College to pay Kirkland for bringing Christianity to the native Oneida tribe. Hancock writes a receipt for the money he’s paying to support Kirkland’s work.

Kirkland’s entire life is consumed with this evangelizing effort among the Oneida natives. He’s learned the Oneida language, identified important native customs, and familiarized himself with their food. He’s also devoted countless hours to understanding spiritual beliefs among the Oneida villagers. He’s especially attendant to the ideas and practices of Sganyodaiyo and Skenandoah, two key members of the Oneida tribe. The Oneida fascinate him.

Kirkland respects the Oneida and wants them to hold onto their way of life as Christian Natives. He knows that a host of groups are straining to push west, French, Dutch, British, and British settlers from the eastern colonies and from different parts of the British Isles. They covet a ridge here, a valley there, a parcel anywhere. As the natives see hunting grounds, the groups see acreage. As the natives see streams and rivers teeming with fish, the groups see mills grinding in power.

The money sent by John Hancock is a pittance next to the complexity of the life Samuel Kirkland is trying to live, in the thousand-piece puzzle he wants to complete with sixty pieces missing.

The tended fires outside Oneida wigwams dry the deer skins and fish taken earlier today. Samuel Kirkland has learned that the village fires serve many purposes, from food and clothing preparation to dancing and social conversation. Aside from the smoke, he smells the first and faint traces of falling leaves. It’s a skill he’s learned to cultivate.

* * * * * * *

(land of dispute)

Southwest of the smoke drifting above Kirkland and the Oneida wigwams is land where the colonies of Pennsylvania and Virginia clash over control and dominance. Six men, including John Penn, governor of the colony of Pennsylvania, are signing today a proclamation steeped in detail about maps, surveys, and boundaries laid down for the past thirty years in the western part of the colony. Penn and his group assert that these written arrangements mark the Pennsylvania-Maryland border. Separately, and also today, the imperial governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, scribbles a letter to British officials in London to denounce “the wild claim” made by the Pennsylvania government. Dunmore fails to include on his parchment that he is currently commanding one part of a Virginia-sponsored two-pronged military invasion of the upper Ohio River valley, the use of arms and armed power to set things right.

Two British colonies on a west-quest, rooted in starkly different aspects of British heritage, following divergent impulses in the violence of Native relations, and seeking wealth and influence according to trans-Atlantic definitions. They are separate rooms of a British house acting like mini-nations.

Smoke can signal peace through a pipe and smoke can reveal a dwelling in flames.

* * * * * * *

(walking toward the State house)

Fires were burning in the hearths of City Tavern in Philadelphia this week. Three days ago, town leaders gave their formal welcome to the delegates of the special congress meeting in Philadelphia. It was quite an event.

They had more than fifty delegates convene at City Tavern in the mid-afternoon. A quick ale or glass of wine was swallowed. The delegates then strolled as a group from City Tavern to the State House, where a contingent of religious ministers met them to offer prayers and blessings. A large dinner was then served with more than five hundred people in attendance, along with music and ceremonial cannon-fire. Thirty-three toasts were given and enjoyed; Toast One, Toast Two, Toast Three, and Toast Four honored the British royal family. First things first.

A day later, on September 17th, the toasts and the music were silent, the glasses and tankards empty, the dinner plates hauled away for cleaning. Paul Revere and his horse galloped into Philadelphia with a formal copy of the Suffolk County (Massachusetts) Resolves (click here) and its piercing language and blatant endorsement of war preparation. The delegates of the “Continental Congress”—fixed with the title from Suffolk County—voted unanimously to approve the hard-hitting Resolves.

The air of early fall had a strong smell of gunpowder.

* * * * * * *

(a crowd at work)

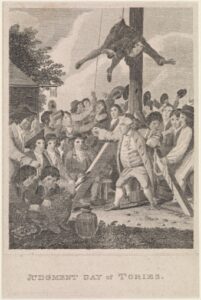

Crowds of protestors in two New England colonies were at the point of gunfire by today, 250 years ago. In East Haddam, colony of Connecticut, protestors confronted a handful of residents who supported British imperial policies and authority. Terrified, most of these surrounded residents openly agreed to renounce their views and to accept the colonial cause. Only Dr. Abner Beebe refused, and he was immediately seized and hot tar poured over his body, followed by a covering of poultry feathers, a show of public torture. In Concord, colony of Massachusetts, a similar set of protestors herded Daniel Bliss Jr and a few imperial sympathizers into a public mock trial. Most of the accused agreed to drop their opposition but some required more “humbling”, as observers called it. Whether they suffered physical torture, verbal assault, or mental abuse was not known. Suffice to say, they got the message in whatever form the bruising and scarring took.

* * * * * * *

(the uniform)

Scenes like these may be why British Redcoat Lieutenant Robert Mackenzie decides today to write from Boston to a long-time professional acquaintance, George Washington. He’s known Washington since the two of them served as officers in Virginia during the French and Indian War, Mackenzie as a Redcoat and Washington in a Virginia unit. Mackenzie recalls clearly that Washington’s greatest ambition in those years was to become a Redcoat officer himself. The guy thought of little else, Mackenzie remembers.

Perhaps that’s a memory Mackenzie is relying on in writing this letter.

Mackenzie writes his congratulations to Washington for his selection and participation as a Virginia delegate in the ongoing “Congress” in Philadelphia. The Redocat officer describes violence and intimidation that he’s seeing in Boston as part of the British military force stationed there. He emphasizes that radical leaders want total independence and nothing else. He hopes that with men like Washington meeting in Philadelphia at the Congress, “abler Heads and better Hearts” will reassert control over the protests and tamp down the imperial-colonial crisis. It better be true, Mackenzie warns, because British General Thomas Gage—whom they both know—is preparing strong British armed defenses around Boston and Massachusetts. Everyone knows who will win that fight.

Let the fire die down before the sparks ignite a bigger conflagration. Hope to see you again soon.

* * * * * * *

(kind of the idea in Norwich)

Someone living near Norwich, colony of Connecticut, has a fire-fighting idea. We need “an Army of Observation” raised strictly for the purpose of keeping the imperial-colonial fire from raging out of control. It would be placed wherever the chances are greatest for serious violence to break out, “near the expected scene of action”. “A preparation and readiness for the defensive or offensive may, and often has, prevented the necessity of execution….”

This unit would be a sort of pre-fire brigade, not so much stopping the fire after it starts but stopping it from beginning in the first place.

Only it can prevent forest fires.

* * * * * * *

Over the course of a single day, we’ve traveled a long way from the cozy fire of Philip Fithian to the desperate wish for Pre-First Responders.

Also

(Strawberry Hill)

Horace Walpole is turning 57 years old next week. He might have a quiet birthday dinner at his resplendent home called Strawberry Hill.

But for now, a week prior, he’s far from celebrating. He’s despondent.

He writes to a cherished friend about a dispute involving the friend and the friend’s nephew. Walpole urges caution, care, and every bit of delicacy that his friend can summon to heal the family breach. Walpole’s words show a deeply-felt appreciation for the value of love, family, friendship.

After proferring his advice, Walpole turns to news of the day. The conditions of nations fill him with dread and discouragement. It’s everywhere, he states, no nation is immune from corruption, malice, brutality. The age and the era seem determined to decline. And as to England’s relationship to the American colonies? Exactly the same. Awful. Hopeless. Descending in a bottomless chasm.

Walpole concludes, “Sorry from humanity for what I see, but as without power of remedying, without curiosity of knowing.”

Put another way:

I see the problems;

I see I have no ability to resolve them;

I see no reason to monitor them.

And thus, to family, to friends.

For You Now

I go back to the fire that so captivated Philip Fithian.

The wood burning in Fithian’s fire is undergoing a conversion. It is energy stored in the wood converting to energy released in the flames, the smoke, the heat, the sound and smell. This is the technical side. All true.

Still true is the fact that the wood once belonged to living. A tree was living, doing its versions of conversions, too, until cut down, stacked, and dried.

And here we sit with Fithian as he stares at the fire, a smoke-like series of thoughts drifting into his mind. He goes backwards into the past, though not far, a few years. This is where he settles for these minutes of reflection. He’s reassuring himself.

There’s a similar action happening when Robert Mackenzie writes his letter to George Washington. It’s the burning of a wick dipped into wax. With this fire Mackenzie drifts back as well, further, to almost twenty years. His reflection is a guided search, looking for a hook, upon which to hang a point presently made for futurely purpose. He’s persuading someone else.

We can look elsewhere for the fires of today. To the stone circles outside Oneida wigwams. To the iron kettle holding the hot tar poured on Abner Beebe. To the lanterns and brick-lined fireplaces of City Tavern and the Pennsylvania State House.

Some burn only once a year, and it’s early fall and time for the first fire.

Suggestion

Take a moment consider: where does your mind go in the first fire closest to you?

(Your River)