Americanism Redux

September 12, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

The land and the ground are so basic you’re seldom aware of them. You assume them. They’re always there. Always.

But the unthinkable can happen. And when it does, the land sways like the surface of the ocean. The ground shakes and cracks and roars. Earth quakes.

I feel an earthquake.

* * * * * * *

(Carpenters’ Hall)

Today, 250 years ago, you could say there’s an earthquake in Philadelphia at Carpenters’ Hall. They’re wrapping up Week One of the “congress” meeting to deal with the problem, crisis, and catastrophe upending colonial life, namely, the Coercive Acts enacted by Parliament against the town of Boston, the colony of Massachusetts, and, increasingly in the minds of colonists, the entirety of the colonial world.

The congress’s delegates are gathering predominantly as strangers. They do what strangers do when meeting: they’ve started forming first impressions of each other and are leaning on any relationships they already have in the Hall’s general meeting room. They’re also laying out basic ground rules for how to debate, discuss, and decide whatever it is that emerges from the collective effort. These first-week dynamics are understandable because they are timeless. We’d do them 250 years later today in 2024 as they were doing them 250 years ago in 1774.

Then, (and this is timeless too) an unexpected thing pops up and blows up Week One’s routine and formalities. Reports arrive in Philadelphia and at the Hall of some sort of attack and violence in Boston, with Redcoats blasting away with muskets and artillery at resident civilians. My God! Panic sweeps the Hall and the town. Soon enough, however, it’s realized the report is rumor sprayed from a drop of truth—British General Thomas Gage had a few soldiers seize containers of stored gunpowder. No violence, no battle, no bloodshed.

The whirling spiral of rumor does contain one additional fact: a careless move can raise underground tensions into a life-shaking reality.

The delegates choose to open the next session of congress with a special prayer. Has the tremor passed?

* * * * * * *

(one of the houses, part of the epicenter)

No. The Hall is not the epicenter today. Go elsewhere for that, further northeast, to southern New England, site of where thousands of people had responded to Gage’s “powder alarm” and where tremors are rumbling into truth.

The Episcopal church minister James Nichols is in Farmington, colony of Connecticut and he’s signing a pledge “never to do hereafter anything contrary to the inclinations and pursuits of the body of the people, provided such pursuits and inclinations are not contrary to the laws of God.” Nichols also promises to educate himself more on “political knowledge” and to avoid subverting the rights of British Americans. Onlookers congratulate themselves that the pledge was orderly and gracious. Okay.

In his new readings and self-learning, Nichols may need to familarize himself with the work of “Antidoulias”, writer of a controversial new essay in a Connecticut newspaper this week. Another of those compelling unnamed authors, Antidoulias tackles the subject of enslavement. He, or she, asks how Americans struggling for their freedom and liberty can be so blind in denying the same to others. Antidoulias narrows the subject to Africa-to-America trafficking of enslaved people. The trade must be stopped on both ends of the transaction. Left unsaid and unwritten in Antidoulias’s essay is the momentum from such action—is it a conclusion of reform or is it a commencement of reform?

In Boston, Gage and the town’s selectmen are arguing about the placement of cannon at the main road entering the town of Boston. Gage insists he was asked to do it, but the selectmen accuse him of planning to launch artillery fire against the community. In addition, a group of Boston’s “mechanics” has proclaimed victory over Gage in their refusal to provide any construction or supply services to the Redcoats. Argue, insult, and deride, it’s another day in the new life of Boston.

During two days of the past week in Suffolk County where Boston is located, a dozen or so men have squeezed into the homes, respectively, of Richard Woodward on one day and Daniel Vose on another to write, re-write, and finalize a document called the “Suffolk Resolves”. Shake, rattle, and roll.

The primary author is Dr. Joseph Warren. The doctor’s writing style is fearless, his vocabulary ferocious, and the agreed-upon content and ideas are perhaps the most inflammatory scratched onto parchment paper since the tea crisis began last December. The earth quakes with every sentence, every paragraph, every itemized resolution starting with the word “that”. Among them is this: “…that the inhabitants of those towns and districts who are qualified, do use their utmost diligence to acquaint themselves with the art of war as soon as possible, and do for the purpose appear under arms at least once every week.”

Beneath the houses of Woodward and Vose, the ground shudders. Muskets hanging on wooden pegs swing against the walls. Old swords rattle in their sheaths. Candlesticks tumble from windows. It’s the equivalent of an underground calamity.

Today, 250 years ago, a horse carrying Paul Revere gallops on rising and falling land in an emergency ride to Philadelphia. A knapsack bounces against Revere’s saddle, tied to the horn. Inside is a copy of “The Suffolk Resolves” that specifically refers to the “Continental Congress”, maybe the first use of that title to describe the gathering. An earthquake is about to rumble through Carpenters’ Hall. Can the structure withstand it? For the moment, the building is quiet. It won’t stay that way when they read Suffolk County’s call for war readiness and Revere rides off back to Boston.

* * * * * * *

(Dunmore, who never receives the return letter)

There are far more than one man on one horse in the Ohio River valley today. 1,200 men volunteering to fight against Native Shawnee tribes are on the march, led by Colonel Andrew Lewis of the colony of Virginia. The men live in Botetourt and Augusta counties in Virginia and Lewis has admitted they have surprised him. Lewis’s confession was about their conduct—they’re behaving well as they walk with horses, cattle, and wagons toward the confluence of the Great Kanawha and Ohio Rivers. The aim is to attack, or threaten to attack, several villages where Native Shawnees live under the leadership of Logan, push them off their hunting grounds, and parcel the land for themselves and Virginia. Further west, great plates of earth lay alongside each other, named later after the largest city in Spain.

Lewis is less pleased with his boss, imperial governor Lord Dunmore of Virginia. Dunmore is at the head of another military force of volunteers. The governor plans to converge his force with Lewis’s. He’s written an order that Lewis received this week, commanding him to change his route and march toward the Little Kanawha instead of the Great Kanawha. As many a commander will do in the future—garbled voices on the cellphone, don’t you know—Lewis acts as if he only half-understands the order, functionally disobeys, and sticks with his route to the Great Kanawha.

Lewis writes a letter explaining his decision. The courier will never succeed in finding Dunmore. The letter is undelivered.

* * * * * * *

(available later in the month)

Most people are living their lives apart from the coming earthquakes and the grinding earth-plates. Robert Hare and Company will be selling a new American Porter beer on Water Street near Carpenters’ Hall. A Continental Congress delegate or two—or ten—might want to buy a barrel of it for relaxation after those long meeting hours. Not far from Hare and his Porter is Charles Wilson Peale, angry over an unpaid invoice; Elie Vallette has still not paid Peale’s bill for painting a portrait of Vallette’s family. Alexander MacWorter begins to prepare to host the upcoming meeting of the “New Jersey Society For The Relief Of The Widows And Children Of Deceased Presbyterian Ministers”, or NJSFTROFWACOD, for short. He’s hoping that scheduling the charity group’s meeting to coincide with the start of the academic year at the College of Princeton will drive up donations to his cause.

And finally, in Charleston, colony of South Carolina, Richard MacGrath buries his head in his hands. He’s almost in tears. You can’t blame him. “The Difficulties and Perplexities of Mind he labors under owing to the Scarcity of Cash,” he writes in a public notice, “render him incapable of carrying on his business with the Spirit Agreeable to his wishes.” He’s decided to sell it all—everything about his art, craft, livelihood, and purpose of work-life. The master woodworker and cabinet-maker is going out of business. Every stick of wood, every wood-shaping tool, every finished piece of work, it’s all up for sale at heartbreakingly low prices.

By day’s end, his hopes and dreams will be nothing more than dust and rubble.

* * * * * * *

An earthquake can tremor for a minute and be done. An earthquake can roar for longer, over and over, and turn land into liquid.

Also

(it’s her)

Catharine Macaulay lives in London, England. She observes politics, reads history and classic literature, and keeps a range of relationships across governmental and civic activities. She knows things, and she…opines, as few can. It’s her unrivaled opinion that the Americans are wasting their time hoping for support for colonial rights against the tough new imperial laws. “The people of this country,” in her view, “are so dead to any generous principle in policy that they regard the Quarrel of the Government with the Americans only as it may affect their own interests. They will snarl a little if they meet with interruption in their commerce but I believe no evil short of the entire destruction of their property will produce an effectual opposition to their career of power.”

In other words, the American protestors are on their own.

* * * * * * *

(bottom right hand corner of the box)

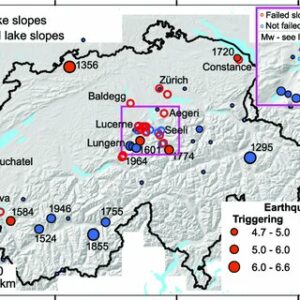

Today, in actuality, a major earthquake strikes central Switzerland. Churches collapse, stone buildings crack apart, chimneys topple over. A loud roar announces the upheaval of the ground, the land in raging tantrum. People scream and crawl-run-stagger from their homes. They seem disoriented in not knowing the source of the disaster, not knowing whether another disaster will follow, not knowing if it’s safe to go back inside, not knowing who is hurt or who is dead, not knowing that the act of merely standing up takes effort to overcome terror and the instinct to crouch and huddle.

The moment is unnatural.

For You Now

So much to say here and yet I don’t want to drown you. The River runs deep enough without me dragging you down.

I believe you understand why the earthquake seized my attention in this Redux research. The image fits. No elaboration needed.

Two points pound away in my mind and seek your reflection. They affect your citizenship and your leadership as we approach mid-September and nature’s change of season.

First, I’m intrigued by the thought of epicenters. We might think Carpenters’ Hall is the epicenter. Certainly, everyone in that moment believes it’s so. The “congress”—now termed “Continental Congress” by some folks in Suffolk County, Massachusetts—was the collective answer to the current problem. Gather delegates, gather outstanding delegates, I should add, and then we’ll see action and progress. We’ll get answers and we’ll see solutions.

But we know what we know and yet I want you to set that aside. From hindsight, we know the Continental Congress doesn’t accomplish that. I tend to think, however, that such a realization might have been accessible in their real-time, too, using insight in the present, living moment and foresight for the future ahead. The meeting at Carpenters’ Hall isn’t the epicenter because it’s artificial; we created it. No doubt the occasion is significant and an amazing feat—the multi-colony gathering of representatives is nearly unprecedented. Yet how long can something artificially made stay effective so as to overturn existing events? Not long enough, I’m afraid.

Which brings us to the second point. The true epicenter.

It’s in southern New England. The back-and-forth between soldiers and civilians, imperial officials and local officials, supporters and opponents and neutrals and the leave-me-alones, on and on—these elements comprise the quivering plates ready to grind into each other with explosive energy capable of shocking destruction and creation. They are ragged, ill-defined, defiant of containment and difficult to shape. They are the epicenter.

Yes, the decisions and events of this epicenter shift and move day-to-day, hour-to-hour in some cases. They’re having meetings, too, though in private houses rather than public halls. They’re drafting statements, too, with sparks practically flying off the page. They have first-impressions and relationships, too, each a potential resource for tomorrow’s action.

I think there’s real wisdom in knowing the genuine epicenter of the actual earthquake.

Lastly, I can’t help myself. Gotta do it.

Take a moment and raise a glass—pour some American Porter—in honor of Richard MacGrath on the final day of his one-man enterprise. As a fellow self-employed person, I feel for the guy. I’ll tell you something he might have said after the tears have dried: the food chain is mighty short for many of us. You’ve got a T-Rex on one end, a three-legged dog on the other, and not a helluva lot in between. And sometimes when you resemble a tasty-looking appetizer, you just can’t hobble fast enough.

Richard, here’s to you. Maybe that rumbling underground will knock the predator on his keester. We can always hope. Stay swift, my man.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: is there an epicenter to the turmoil of 2024?

(your Swiss River)