Americanism Redux

October 24, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Such a big day. I know it is. Big, big day. Amazing.

But I wonder: is this how I’ll always think of this day?

* * * * * * *

(Carpenters’ Hall)

Today, 250 years ago, a month-and-a-half has gone by and the colonial delegates at the special Congress are wrapping up their work in Carpenters’ Hall, Philadelphia, colony of Pennsylvania. Just a few more hours now and the group of them remaining will begin the journey back home.

They’re cleaning up the final language in two documents, one a “Petition to the King” and the other “An Address to the People of Quebec.” Once finished, the documents will be sent to their respective addresses.

One other thing: a few days earlier, they completed and endorsed a “Continental Association” that listed in detail the unfolding of a broad economic boycott of England until the effective redress of colonial grievances.

In each of these documents the opening statement had the same frame: “We his majesty’s most loyal subjects, the delegates of the several colonies of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts-Bay, Rhode-Island, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, the three lower counties of Newcastle, Kent and Sussex, on Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, and South-Carolina, deputed to represent them in a general [used in 2 documents] (or) continental [used in 1 document] Congress…”

It’s a big, big, big day.

* * * * * * *

(Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address)

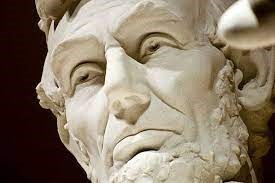

How big? Well, let’s fast-forward to the very first speech Abraham Lincoln delivers as President of the United States.

In his First Inaugural Address of March 1861 Lincoln states:

“…we find the proposition in legal contemplation the Union is perpetual confirmed by the history of the Union itself. The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed, in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774.”

In other words, Lincoln points to the work of the Congress by late October, 1774, 250 years ago in our real-time.

As we might say, he gets it.

Yes, it’s a big, big, big day and set of days.

* * * * * * *

(three documents of a big day)

The “Petition to the King” is straightforward in laying all the problems forced upon the colonies since the French and Indian War that ended in 1763. The purpose is to seek the King’s “interposition” to repeal and make better the various harmful actions taken by politicians who are either misguided, malevolent, or both.

The “Address to the People of Quebec” describes the freedoms, liberties, and rights of people in the British colonies and, by extension, available to people who are capable of recognizing and living in this natural and God-given state of being. This document reaches out to a place and people who had been longtime and wartime enemies to the British colonists.

The “Articles of Association” sweep across vast realms of daily life and include a mechanism of enforcement in following these broadly defined rules of resistance. Moreover, in a stunning context of revolutionary moment, the delegates from northern, middle, and southern colonies agree to end the external acquisition and trade of foreign enslaved people. So urgent in this point that the delegates elevate it to a position of prominence in the document.

Yep, it’s big.

* * * * * * *

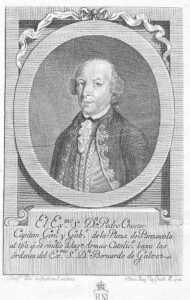

(Peter Chester)

So big, in fact, that the British imperial governor of the colony of West Florida, Peter Chester, decides to suppress the formal written invitation he sees just now at his desk. The Congress in Philadelphia had hoped to communicate with Assembly members in Pensacola, asking them to choose delegates to send north to Pennsylvania.

Chester wants no part of it and seeks to keep the Assembly in ignorance of events flashing and crackling in Philadelphia.

* * * * * * *

(Penelope Barker)

Today, 250 years ago, Penelope Barker works herself to the point of exhaustion in Edenton, colony of North Carolina. She’s been writing letters nonstop it seems, reaching out to women in and near Edenton for tomorrow’s big meeting. She’s sensing that a massive shift is underway in the colony; she’s helped make it so.

Upwards of fifty women are said to be gathering tomorrow to write, sign, and adopt a pledge to stop immediately the use of English tea and cloth as a sign of solidarity with the colony’s “Provincial Congress” convened three months ago. The tea and cloth are only first steps—from there they’ll expand the ban to every other article brought in the bottom of a British ship.

These women are influential, with personal and family networks of contacts that run across North Carolina.

Tomorrow, they’ll seize the day and make it big.

* * * * * * *

(his headstone)

Can you see the headstone? I can’t. Too many people here. Let this crowd disperse and we’ll get closer before the night falls. I don’t want to be at the Granary Burial Ground after dark. Too spooky.

Today, 250 years ago, you’re in Boston, with hundreds of people at this well-known cemetery. Fresh dirt marks the new grave. Chiseled into the stone is “William Molineux.”

He died unexpectedly two days ago. The crowd is here because he was a wild man—wild for liberty, wild for colonial rights and all rights, wild in the extent and extreme he would go to as a leader of the colonial protest movement in Boston since 1765.

Molineux was willing to threaten anyone, adult or child. He was willing to destroy property and, if need be, any person who got in the way. He was willing, and was one of the first, to encourage the adoption of Native disguises in the destruction of Boston’s tea last December. He was willing to hold a knife to his throat in public meetings and threaten suicide if he felt his harsh tactics were in danger of being softened or moderated.

And now, after sputtering his last words “O save my Country, Heaven”, Molineux is dead. Those who support him say British Redcoats put poison in his food or ale. Those who oppose him say he likely did what he’d threatened to do—commit suicide.

Some days are big because of the silence, of the sound not heard. The voice of Molineux is stilled, and that equates to a big day.

* * * * * * *

It is a historic day.

Also

(the tomb of Clement XIV)

Comte de Vergennes is the foreign minister in the court of French King Louis XVI. Vergennes writes a letter today to two Catholic cardinals affiliated with the French monarchy.

“There reigns among the cardinals a dull ferment which announces a most stormy conclave.”

Vergennes is referring to the boiling pot of conspiracy, back-biting, backstabbing, and backhandedness that is dominating a papal conclave now occurring at the Vatican in Rome.

A month ago, Pope Clement XIV was found dead. Reports, rumors, and everything in between have been flying across Europe that he was murdered. His enemies were many, that’s a fact, primarily because of the despotic way in which he declared that Jesuits were no longer part of the Catholic Church. At his order, Catholic officials are expected to root out the Jesuit order.

The conclave of twenty-eight cardinals to choose the dead pope’s successor has descended into two factions—pro-Jesuit and anti-Jesuit—and each of the two factions has split into a half-dozen smaller cliques and micro-groups.

On opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean, from Philadelphia to Rome, gatherings of people wrestle with the problems that have brought them together.

For You Now

I’ve frequently gone back to Lincoln’s First Inaugural in the work I do. His decision to land on autumn 1774 as the start of the “Union” in America is monumental. Lincoln is a word-nut, like me, and his linkage of American, union, and 1774 deserves study and attention. It also deserves action.

He invokes these words at a time when secession has hit top speed but actual fighting and violence has not. Remember that it’s March 1861, before Fort Sumter in April. Lincoln believes war is unlikely and that the rub of friction is in the fulfillment of the federal government’s duties, including delivery of the mail. We’re a long way from emancipation.

But it’s the things that happen after his speech and the things that happen after autum 1774 that grab attention and grow in memory. The cannon at Sumter, the bloody angle at Gettysburg, and the Second Inaugural Address will define the most important days. So too will the musket shots at Concord Bridge and along Lexington Road, the Declaration at a space across from Carpenters’ Hall, and the Constitution in the shadows of the same desks and chairs.

Understand that the colonies have had a “congress” before that produced a collective statement, action, and policy. That was in 1765-1766 with the Stamp Act protests. Indeed, I think they take some comfort in 1774 in telling themselves (some more than others) that they’re still following a model of those earlier years. Nevertheless, it doesn’t compare to the scope and range of 1774. The list of colonies is significantly larger, for one thing, and the names of “general” and “continental” Congress, for another, hint at their own down-deep realization that they’re stepping out of the shadows of ’65-’66. This is broader, this is bigger.

Things happen after That Very Big Day which are themselves still larger in scale and deeper in depth. That doesn’t mean, though, we should pass over that earlier day, once-heralded and now-forgotten. It has richness for us from its own accord, a secret truth we ignore at our cost.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: is there a day that once was important and now has been lost? And now before it’s too late, what can we gain from the day’s restoration?

(Your River)