Americanism Redux

November 7, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

We’ve got to make sure about these elections. And check the clock on your phone about spring-forward and fall-back.

* * * * * * *

Today, 250 years ago, the people of Philadelphia in the colony of Pennsylvania learn of the strict process of election that will occur in the coming weekend. They’ll be voting for a “Committee” to have charge of local governmental authority between now and the coming spring when “the General Congress” reconvenes. It’s all about getting it right.

The procedures are clear. If ineligible voters are found to have attempted to vote, these violators will be publicly accused of the offense with their names published in newspapers. A set of instructions defines the geographic lines of voting districts, a panel of judges will oversee the process, two-dozen men will monitor the election of voting inspectors, and voting inspectors will receive and count the ballots by the end of the day of voting for sixty representatives to the “Committee”.

Specific, stream-lined, organized, and verifiable. That’s the appearance sought by the local government of Philadelphia and that’s the feeling conveyed in the announcement by local officials.

* * * * * * *

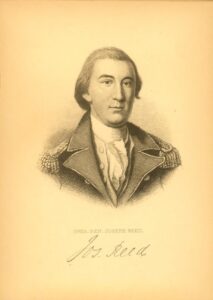

(Mr. Reed)

Joseph Reed of Philadelphia knows the deeper story of this “Committee.” He describes the new “Committee’s” primary task as having responsibility “to carry the Association (the economic boycott) of the (Continental) Congress into Execution.” He judges that it’s a necessity because “there has been a stagnation of Public Intelligences and Advices” since the Congress disbanded and left Philadelphia ten days ago. For all the enthusiasm generated by the Congress’s three final public documents, Reed senses a steep drop in public energy and activism within the colonial rights movement. Reed is deeply suspicious of the impact Quaker leaders in Philadelphia will have on the election. What’s true in Philadephia, Reed asserts, is triply true in New York City where “the great Cause is suffering” from a reversal of momentum and enthusiasm for colonial rights. Reed’s despair even runs into his private fears that his mailed letters could be vulnerable to theft and subversion. Trust and confidence are dwindling commodities.

* * * * * * *

(the waterfront of Yorktown)

Where we’re standing right now is historical ground, a historical spot. Just not yet, at least not forward yet. Instead, we’re veering back to almost a year ago and making history backwards. Our feet stand on historical ground now because of what happened then, not what will happen in the future. At least for the time being.

We’re at Yorktown, colony of Virginia, and we have our hands firmly on two chests of tea. Yes, tea imported from England and landed here at this Virginia port on a British vessel. Our provincial congress last summer was one of the first to vote to ban the stuff but evidently the captain of this ship doesn’t read the London newspapers. Or maybe it was never reported there.

Regardless, we’ve decided to toss the tea overboard just like they did up in Boston almost a year ago dressed as Native warriors. We don’t have our faces painted, we don’t have feathers tied to our hair, and we don’t yell in that shrieking style that is so signature to Natives in combat. We’re just heaving the stuff overboard.

The importer’s punishment will be a public apology printed in a local newspaper. The sea captain’s punishment will be to return to England with a cargo-less ship.

In seven years, nearly to the month, these same waters of York River will flow by as a British Army surrenders to American captors, while a military band plays “The World Turned Upside Down.”

Just not yet, as you know. Just not yet, as they can’t possibly imagine.

* * * * * * *

(Charleston Tea Party)

So, is this what full-circle looks like? It’s a few days ago in the first week of November, and yes, they’re at it again—another tea party almost a year after the Boston’s, except that we’re toward the southern end of the Atlantic Coast.

Say hello to fast-thinking and fast-talking British sea captain Samuel Ball.

Staring at the furious crowd around him, Ball says nervously, “No, not me, it wasn’t me, it couldn’t have been me!” He and the crowd are on the docks of Charleston harbor, colony of South Carolina. They’d learned his ship had seven chests of British East India Company tea, “the mischievous Drug”. Ball was envisioning hot tar on his skin, a rope around his neck, or set alone in a boat on the high seas when he blurted out that his assistant must have accepted the wooden boxes for a short time when Ball was away from the ship. Yes, yes, that’s it, my assistant, damn him, we were docked while still in London and I wasn’t there for a bit…there’s simply no other explanation….

The crowd pondered a moment as the terrified Ball watched eyes darting back and forth in the group. He’s innocent. He’s lying. He’s hard to read. He’s trying to trick us into accepting tea and undercutting what the rest of the colonies are doing. Then…

Okay, we believe you. Stand aside.

They break open the boxes and pour the tea into Charleston’s harbor.

Ball exhales. No other punishment. Barely hours later and by the looks of individual people who were in the crowd, you’d never know the event had even happened.

* * * * * * *

(Mr. Drayton)

Until yesterday, November 6, that is, 250 years ago.

William Henry Drayton is in Camden, colony of South Carolina, about 120 miles from Charleston. He picks up a gavel and whacks it down hard on the desk at the front of the courtroom. Whack! Whack! Whack!

What in God’s name is he hitting? Surely one whack is enough.

A visibly upset Drayton calls the meeting of the Camden district grand jury to order. As a newly appointed assistant judge, He barks out to the twenty-two person group and gives them a clear command: “By the lawful obligations of your oath, grand jurors, I charge you to do your duty; to maintain the laws, the rights, the Constitution of your country, even at the hazard of your lives and fortunes.”

Loud and clear, they hear him, and they get to work.

Talking, scribbling, talking some more, striking out and scribbling again, they work furiously to draw up, write out, and put forth three grievances: access to Christianity, wildly fluctuating entertainment prices, and Parliament’s power to rule over the colonies. Quite a trio. From there, they pound away with resolves and resolutions focused on consent of self-government and guardrails against unchecked power.

Drayton had been an imperial man a decade ago, a supporter of British imperial rights. Now, he’s whacking the desk for all he’s worth and unleashing a pent-up outrage among the twenty-two grand jurors of Camden. A ten-year River of time with all its bends and turns.

Also

(maybe near Quincy’s bearing)

Josiah Quincy Jr is in the middle of the north Atlantic Ocean, twenty-eight days at sea from Boston to London. He’s on a secret mission, a concealed quest. His goal is to offer whatever he can to help open the minds of British lawmakers that they might alter the Coercive Acts imposed on Massachusetts and, by extension of logic of implication, the rest of the British colonies in America.

While writing today, 250 years ago to his “dear partner of my life”, he laments the slowness of the trip as he approaches the British coast from latitude 49, 45 min north, Atlantic Ocean.

He’s using his time monitoring his health, combing through his thoughts, and staying alert to any American or European information he may encounter from passing vessels.

His final lines: “I think I was never better, if so well, in all my life.”

* * * * * * *

(where Burke represented)

Edmund Burke writes a speech for his voters in the English town of Bristol. He explains that he owes the voters everything, including his judgment. He’ll listen to their opinions, respects their opinions, and act on their opinions as their elected representative. But he also owes them an honest expression of what he thinks.

He also owes them a description of the legislative body to which they elected him. Here, he says, is that description: “Parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests; which interests each must maintain, as an agent and an advocate, against other agents and advocates; but Parliament is a deliberative assembly of one nation with one interest, that of the whole, where not local purposes, not local prejudices, ought to guide but the general good resulting from the general reason of the whole.”

These are the sights of the eyes and the thoughts of the mind of Edmund Burke, member of British Parliament and supporter of the American colonial rights movement.

* * * * * * *

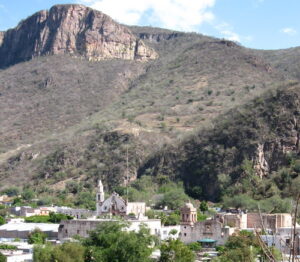

(before this mountain started shaking)

The stillness stops when the shaking starts. A loud roaring sound fills the air. Land rolls in motion up and down. Baked ground splits in zig-zag lines. Rugged mountains crack and rock slides begin. A severe earthquake strikes this already harsh world of extreme heat and rare moisture.

Local workers fear for their lives, an occurrence they normally reserve for their underground world of silver mining. Today, 250 years ago, this feeling is on the surface in the stone-and-mud huts where they live in Bolanos, about 250 miles east of the Pacific Ocean in west-central Mexico of New Spain.

In a later era when such measurements are possible, the upheaval of this day reaches 6.0.

Tomorrow, it’s back down beneath the crust of the earth to find silver for the wealth that fuels the Spanish Empire a universe away from these workers, the descendants of separate Native tribes long blended and long vanished. To the people who control them, they have life but don’t live life down in the mines.

For You Now

We’ve got time in two forms.

As our first form, we’re seeing the gap of time ahead. The gap is made by an event like the Congress in Philadelphia and the work it managed to complete, a set of three documents made from compromised viewpoints. That’s one side. But a gap needs a paired side—the far side—or it never takes a shape and stays as infinite, unbounded, and undefined space. So, the other side is England, London, Parliament to nail it down to a specific location. The work of the Congress is arriving as information to a destination, the object of the documents themselves.

It takes time to cross the gap. Ask Josiah Quincy Jr.

As our second form, we’re seeing the gap of time behind. This is not so much a physical proposition, not an exercise in moving from one point to another point as a substance of information. Our second form is less about distance of traveled space and more about distance of lapsed time. I’m referring to the Boston Tea Party in late 1773 and the still-occuring versions seen in late 1774 at Yorktown and Charleston. A recurrence of the original event brings with it a context, a setting, and a perspective, all drawn from linkage to the event in the earliest moment of birth. The two tea parties in more southern waters have surprisingly unique characteristics when set alongside the original in the cod-rich environs of Massachusetts Bay. Those uniquenesses can only be discovered with a knowledge of passed time.

Ask Samuel Ball if he was grateful for the crowd’s knowledge of Boston.

What do we do with our two forms of time?

The time gap ahead: from it will come the challenge of next.

The time gap behind: from it will come the foundation of now.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: fix your eyes on your smartphone and ask yourself which is more deeply altered by it—the time gap ahead or the time gap behind.

(Your River)