Americanism Redux

November 14, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Both a boulder and a ball roll. The similarity ends there. It’s 250 years ago—let the bouncing begin.

* * * * * * *

He was sky-high, up on a cloud in his excitement. It’s his time of the year and it’s a special year all by itself!

Reverend Ebenezer Parkman dates his years differently than most people. For him the year begins now, toward the middle of November rather than the start of January. That’s because it’s when his own church, the First Congregational, was first organized and opened for worship in Westborough, colony of Massachusetts. And now in this year of 1774, this “New Year” is also a half-century of existence, or the “Jubilee” as he calls it. It’s an occasion for celebrating.

Didn’t last long, though. Barely a day later and today, 250 years ago, Parkman is hearing from his friends that people in Westborough snarl when they say his name.

Why, for heaven’s sake?

Get ready to be shocked, Reverend Parkman.

Earlier this week, in a recent public town meeting, Parkman was asked to speak to the group. Remember, he’s been somewhat cautious in getting into position as a full-throated supporter of colonial rights and the current protests. Remember also that the imperial-colonial crisis is on everyone’s minds and hearts. Parkman would have added “souls” to that as well. So, in stepping to the front and beginning to speak to the town meeting, Parkman decided to start his requested remarks by reading a passage of Scripture from the Bible. Seems like a not-too-surprising choice for a pastor to make in a crisis that begs for God’s guidance, mercy, and wisdom.

Well, evidently, not everyone agrees with that, not by a long shot. Parkman’s open reading of Scripture was a jolt to the meeting’s attendees. They disliked hearing it and disagreed with his decision to read it. And the meeting was over—at the always important meeting-after-the-meeting—they’d discussed it among themselves and concurred that Parkman had overstepped.

Parkman had no idea of any of this until his friends told him.

He’s left to wonder about his community’s collective understanding of God in this momentous period, in this catastrophe-grown-from crisis. Are we God’s people? Or are we something else? As a Christian minister, does he speak inside the church or outside in the public square?

It’s a rough start to Parkman’s year of Jubilee.

* * * * * * *

(the wharf at Mt Vernon)

Tie the rope off right here. Let’s get out of the boat and we’ll head up the bank to the house from the wharf. Prepare yourself for a walk up the steep incline. But it’s worth the effort, the house looks more gorgeous with every step we take. We’ll stop at the top and turn around for an amazing view of the Potomac River. We’ll let someone know we’re here at Mt. Vernon and would like to speak with him.

Philip Richard Francis Lee is 27-years old and he’s just walked with two other men from a vessel secured at George and Martha Washington’s wharf on the Potomac River. Lee and his two comrades are the officers in a group calling itself the “Prince George County Independent Company”. They and approximately fifty men in the county have banded together into this volunteer military unit, ready to do what needs to be done in case of emergency, which everyone assumes will pertain to the imperial-colonial crisis.

The unit is all of seventy-two hours old.

Lee’s trio wants the unit to serve under the command of Washington within a formal Virginia military structure. Lee also wants Washington’s advice on “the fashion of their uniforms” and to share with him the “company motto” they’ve created.

They’re like a team, with common clothing, a slogan, and even a flag to rally beneath. Having Washington’s blessing will be a finishing touch to an act they hope brings honor and victory, though what either will look like no one really knows.

* * * * * * *

(Morgan)

Daniel Morgan isn’t at Mount Vernon but he does know George Washington. They served together in the French and Indian War, Washington as an officer and Morgan as a wagon-driver.

Also, Morgan isn’t now standing on Virginian soil, though he is a Virginian colonist. And he’s not with a new unit of volunteer-soldiers but instead with a semi-new unit of volunteers who’ve been in service for about two months.

Daniel Morgan is the captain of militia from Frederick County, gathered up to serve in the armed expedition organized by Lord Dunmore, British governor of Virginia.

Morgan and his men didn’t make it in time to fight Native warriors from the Shawnee, Delaware, and Mingo tribes at the Battle of Point Pleasant two weeks ago. The combat accomplished what Dunmore had hoped—it forced the Native coalition to leave the upper Ohio River valley where many Virginians, Washington among them, had secured thousands of acres of land. Colonel Andrew Lewis and his Virginians had waged that battle and forced the Natives to withdraw from the field where the Ohio joined the Great Kanawha River.

Today, 250 years ago, Morgan’s men are near the juncture of the Ohio and Hocking Rivers, not far from Fort Gower. A man only recently self-taught to read and write with any effectiveness, Morgan is still thinking of a meeting he had a few days back, a meeting that produced a document, a document that declared a commitment, a commitment that he knows could amount to a last will and testament.

* * * * * * *

(where the fort was)

It is a remarkable document created at Fort Gower.

The Virginian officers who had served under Dunmore were at the fort along the edge of blending waters. This was the place where, after “three Months in the Woods”, they first learned of the troubles afflicting Boston and Massachusetts as well as the meeting of colonial delegates in Philadelphia. “It is possible,” they acknowledged, “from the groundless Reports of designing Men, that our Countrymen may be jealous of the Use such a Body (this army) would make of Arms in their Hands at this critical Juncture.”

We know some people may not like us.

“That we are a respectable Body is certain, when it is considered that we can live Weeks without Bread or Salt, that we can sleep in the open Air without any Covering but that of the Canopy of Heaven, and that our Men can march and shoot with any in the known World.”

We have bonded together in a dark place.

“Blessed with these Talents, let us solemnly engage to one another, and our Country in particular, that we will use them to no Purpose but for the Honor and Advantage of America in general, and of Virginia in particular. It behooves us then, for the Satisfaction of our Country, that we should give them our real Sentiments, by Way of Resolves, at this very alarming Crisis.”

We can be relied upon.

After creating this striking opening statement, they stopped writing and began talking about the “resolves.” They fixed on two of them.

One was a declaration of allegiance to King George III that was superseded by the “liberty…interests…and just rights” of America. If these three things were threatened, they would defend America, though “not in any precipitate, riotous, or tumultuous Manner, but when regularly called forth by the unanimous Voice of our Countrymen.”

The other was a declaration of respect for Governor Dunmore and the fact that he “underwent…great Fatigues of this singular Campaign from no other Motive than the true interest of this Country.”

We keep our powder dry.

The officers signed their names and pledged to publish the document in a Virginia newspaper, this work done inside the walls of Fort Gower, in the woods of the Ohio valley, in the region west of the Appalachian and Allegheny Mountains.

* * * * * * *

(Neahwa Park in western New York)

He won’t wear the long pants favored by white men.

Neahwa is a member of the Shawnee tribe defeated in the Battle of Point Pleasant. Tall, muscular, with long dark hair and knife-sharp eyes, he is one of four Shawnee warriors who have consented to be hostages to the Virginia soldiers. The four warriors are a type of insurance policy. They will be safe, unharmed, and well-treated so long as the Shawnee tribe observes the conditions of the treaty they signed after losing at Point Pleasant. Among the conditions are a pledge of the Shawnee to not hunt anymore east of the Ohio River.

Outside Fort Gower, Neahwa is doing his best to adapt to the life he’s living for whatever time he is with the Virginians. He wears shirts like they do, eats like they do, drinks like they do, and so on.

The only thing he won’t do is wear long pants like they do. He’ll only wear his breechcloth, a traditional garb of the Shawnee. Nope, captor, wear your own damn pants.

* * * * * * *

(people on the line)

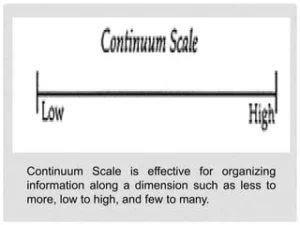

Today, 250 years ago, a white man and a black man are on the run. They live on different points along a continuum of forced labor in the British colonies. They’ve never met and they never will meet.

The black man is Peet, with no last name. He’s 27-years old, five-and-a-half feet tall. On his face and neck are jagged scars made by a knife, likely in an attack or fight. He wears a large red coat and thick long pants. His life belongs to someone else, until it’s not. Believing the “not” will never come, Peet has escaped in the colony of New Jersey.

The white man is James, last name of Bell. James Bell is 40-years old, a miner, from Yorkshire, England. He has no distinguishing features. He wears a dark blue coat and is carrying a large set of small bells, perhaps in relation to his name. His life belongs to someone else for a period of five years or so, stipulated in a contract that outlines what he owes and is owed in the arrangement. He is unconvinced the agreement will be honored and thus he escapes in the colony of Maryland.

At one end, the worst end, of the Forced Labor Continuum is the total loss of freedom and liberty for an indefinite period of time. Moving away from that end, the loss continues but in intervals is reduced, limited, and curtailed. The amount of time when freedom and liberty are denied reduces, too. Men, women, and children can be found at various points along the Forced Labor Continuum. It’s a phenomenon that spans the colonies, the continent, the earth.

Also

(in his happier days)

People in London, England who follow the doings of Parliament are still talking about Thomas Bradshaw. He’d been elected to the House of Commons from Saltash, lost re-election, and then won back his seat through a special petition. A member of the entourage surrounding the Duke of Grafton, Bradshaw had become engulfed by debt and suffered lately from severe illness. Despair and hopelessness are said to haunt him.

A few days ago, Bradshaw put a pistol to his head and pulled the trigger. Dead by suicide.

The smoke from the shot has dissipated, but the incident spreads a cloud of nervousness over some corners of Parliament and the imperial government. Whiffs of unpredictability drift in the wind.

* * * * * * *

(Trinh Sam)

A hundred years of a loose, uneven sort of peace comes to an end tonight, 250 years ago. The latest ruler of the Trinh family—Trinh Sam—has decided final details of tomorrow’s attack on the Nguyen family’s fortress in Hue. For the past three hundred years, the two families have clashed over control of the region known as Vietnam. The Trinhs rule in the north, while the Nguyens rule in the south. The struggle had quieted in recent generations.

Until tonight.

For You Now

We know a war will begin in the colonies soon. It marches toward us with inevitability. With it also comes an assumption of linear motion, moving from there to there to there. Neat, clean, orderly.

Today’s entry shows you in full form the brokenness of it all, the shatteredness, the misfitting pieces and ill-shaped parts that actually mark the flow of time in the river of their lives.

The unpopularity of the public reading of Scripture stuns Ebenezer Parkman.

Philip R.F. Lee’s new unit of volunteer soldiers look to George Washington for approval and support.

The two-month volunteers under command of a British governor in the woods of the Ohio valley set their own conditions and definitions for helping beleaguered colonists in Massachusetts.

Three men—white (James), black (Peet), and native (Neahwa)—encounter a change in the liberty and freedom of the life they want to live.

A civil life surrenders on a British island and a civil war renews in a Vietnamese jungle.

Suggestion

(Your River)

Take a moment to consider: what’s the biggest recent jolt that will be forgotten twenty years from now?