Americanism Redux

March 28, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

(together, voluntarily)

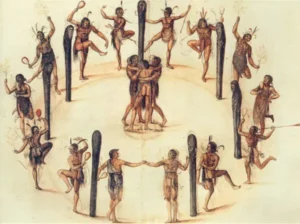

Do you belong? To a club, a group, some sort of collection of people outside your family? Together, you and they meet each other, see each other, spend a period of time with each other. You, and they, are joined for a while around whatever it is that brings you together. Belonging.

A famous observer of America and American ways once noted that “in no country in the world has the principle of association been more successfully used, or more unsparingly applied to a multitude of different objects, than in America.” These are the words of Alexis de Tocqueville, written around the time of the sixtieth birthday of the Declaration of Independence.

Boil it down from the mind of a French aristocrat for us now and you get this:

Voluntarily, they belonged.

Do you belong to others in a group now? And what is the voluntary tie that binds?

It’s today, 250 years ago.

* * * * * * *

(in the streets of Philadelphia)

Club roots run deep.

Today, 250 years ago in Philadelphia, colony of Pennsylvania, William Ball is a Baptist preacher who has a second job, or calling, or passion. It’s the voluntary club for which he serves as clerk: “The Society for Promoting Learning Amongst The Baptists,” organized in Philadelphia. The name is long but self-describing. Ball has decided the group needs to meet again. He submits a public notice in the town’s most popular newspaper. Let’s gather next week.

Subsurface point: every week there are newly published pamphlets, printed speeches, and written announcements about the imperial-colonial crisis and you’re at a disadvantage if you can’t read and have to rely on hearing someone else reading them to you. And how will you know if they’re reading or summarizing on their own?

Just a few cobblestone streets over from where the Pennsylvania Gazette is printed, another long-named and clear-titled club calls for a meeting: “The Society for the Relief of Poor and Distressed Masters of Ships, their Widows and Children” will be also be meeting next week. You’ll see them gather at the London Coffee-House.

Subsurface point: if something happens to our ability to use the port and its water-borne transportation, guess who will be hit hardest the first? The people whose livelihood starts and ends on the water.

The voluntary clubs are getting busy, though they can’t foresee the scale of trouble ahead.

* * * * * * *

(a common sight to Miss Devine)

Maybe she sees it or maybe she doesn’t. Hard to tell.

Unmarried and unattached, Magdalen Devine is one of Philadelphia’s most recognizable women. She owns an upscale shop of nearly unimaginable variety of inventory, which often means a kind of sixth sense for anticipating trends and seeing around troubled corners. Today, the sixth sense is full-on. For some reason she’s not sharing, she’s decided she’s done—closing down, selling out, packing up, leaving town. Off to London on the next ship, off as worshipper in a new parish in the Church of England. She’s been active in supporting volunteerism across Philadelphia, this community where every street intersection seems the site of a volunteer-group meeting. No more for her. She’ll be missed by the clubs and groups, the efforts and causes. The air is not right, according to Miss Devine.

They won’t see her again until after the unknown future war between England and the American colonies is waged and ended—she’ll return in the form of a will to be probated, its items dispensed among family, friends, and former volunteer-neighbors.

Perhaps some folks will volunteer to honor her memory.

* * * * * * *

(he’ll be looking for Colvin Ferry in three Christmas’s time)

About thirty miles away, along the Philadelphia-to-New York City Road, Patrick Colvin and Renselaer William want to form a volunteer group for a specific money-making reason. They’re in Trenton, colony of New Jersey, and they’re seeking to start of group of “subscribers” to their newest venture, the opening of a ferry service across the Delaware River in Trenton. They’re publicizing inducements to entice people into their group: lowest rates for a four-mile stretch of the river; right off the high-traffic Philly-NYC Road; and requiring only a hundred yards of actual ferry travel over the swift river current. Investors and customers are volunteers under different names.

No one knows that three Christmases from now a Continental General named Washington will be leading a rag-tag group of grizzled soldiers across these ice-choked waters. They’ll use the ferry and its operators for their own Gloucester-style boats, their frozen hands gripping oars and poles, powered by aching arms, shoulders, and backs. It will be a desperate, last-chance strike against the enemy. The code-phrase on that night: “Victory or Death.”

But that’s the future. In the present, the now, Colvin and William seek their volunteer-subscribers for the new ferry.

* * * * * * *

(where they hope to form the group)

Even in formal and legalistic entities, voluntary groups can rise and coalesce.

In the colony of Rhode Island, four men—Stephen Hopkins, Samuel Hopkins, Ezra Stiles, and Moses Brown—are quietly meeting with members of the colony’s legislature today and in the days ahead. Each of them speaks with one, or two, or three members at a time, talking about the need for a ban on the importation of enslaved African men, women, and children. The conversations are delicate, careful, measured, private. No one is commanded, directed, or ordered-about. The club or group they’re building is unofficial and unnamed—made possible if only for a while by interest, outlook, and an agreement to say and vote “yes” on a proposed ban in a legislative bill. It’s not necessary that the group’s members like each other, but it would surely help if they did.

The habit of volunteering outside of politics and office-holding is an important step in bringing this internal club to life.

* * * * * * *

(what Emistesego hopes to avoid)

A different pair of approaches to a related problem is taken today, 250 years ago, in the colony of Georgia. Interracial relations are the framework for the latest of a series of problems: a Native man has been murdered by a man native to the colony.

Leaders on both sides of the tensions have contrasting methods of building a voluntary base of support for their actions.

Emistesego is a leader among the Upper Creek tribes, the home of the murdered Native, Mad Turkey. Emistesego attempts today to continue to persuade Native members of the Upper Creeks to not take on a “warrior” attitude and seek to do violence against white Georgians. He’s urging them to stand down, to wait and see if white officials can offer justice for the murder. Emistesego knows his ability to succeed depends on persuading a handful of clan and family leaders within the Upper Creek villages. They’ll either agree or they won’t, likely for any of a hundred reasons. If he persuades them, they will persuade everyone else. That’s how the volunteerism will work, if in fact it works at all.

The opposite view is taken by the royal governor and chief executive of the colony of Georgia, James Wright. Wright issues today a “proclamation”—written with a swirling style and embossed with impressive figures—ordering a reward to a posse to track down Thomas Fee, Mad Turkey’s killer. Wright invokes his powers as the primary political official in Georgia to make his proclamation. It is total command-and-control, an unapologetic use of authority traceable upward to the British monarch and, ultimately, to God. At least that’s what the writing says.

On one side is to volunteer to refrain from war. On the other side is to volunteer to enforce punishment. In the middle is an unknown flow of actions, decisions, and consequences impossible to measure and impossible to predict.

They’ll become known in the fullness of spring.

* * * * * * *

(where Adams will meet his group, Treadwell’s Inn)

Give me a minute, I need to step outside and hear the birds singing in the sunrise.

That’s the wish of John Adams in his travels this week to Ipswich with his friend, Josiah Quincy. Such a request doesn’t seem to fit Adams with his serious bent, his visible ambition, his touchiness at the slightest slight. Yet it is him, inside. He loves the land and the creatures on it and every so often, this love slips free and wings into view.

He’s heading to a loosely arranged meeting of a few lawyers tomorrow at Treadwell’s Inn in Ipswich. He and they will be testing men seeking their credentials as new lawyers. They will quiz them on legal procedures, powers, and rulings. They’ll also be hearing from five candidates for new judgeships. Adams knows that a variety of personal interests and agendas separate the five men. He knows that one of them is endorsed by the “Liberty Men” while another is a fervent supporter of King George III and imperial power.

Tonight, though, Adams thinks about a credible report that a tavern owner has heard from England. Colonial rights leaders in Boston have received secret letters that they were to be punished for the recent anti-tea protests. It’s a serious threat that Adams believes “will keep their heads down.”

And how will such news affect the group of lawyers who have volunteered to help guide new members of their profession and new judges to the bench?

* * * * * * *

(dark times in Marblehead)

John’s cousin, Samuel Adams, has similar worries. He is deeply troubled by news out of Marblehead, colony of Massachusetts. He’s learned that the town has exploded in violence and threats of further violence over a strange blending of the tea protests with other local problems, namely, the new hospital built for patients taking smallpox inoculations. The hospital split the town in two—rich and well-off siding with having the new facility, while less-rich and less-well-off siding against it. Making things worse was a decision—voluntarily reached by a group of volunteers—to beat up a group of pro-hospital people. They adopted the tactics of Native-disguised tea protestors but used black paint on their faces and dressed in seafaring clothes and hats, likely because they precisely were seafaring men. Things were spinning terrifyingly out of control, and Adams had written to one of his proteges, Elbridge Gerry, that “the skillful pilot will carefully keep the helm, and so steer the ship while the storm continues, as to prevent, if possible, her receiving injury.” It’s far from guaranteed.

Adams hopes that Marblehead and other communities will embrace the all-volunteer effort being led by William Goddard in establishing a new “Constitutional” postal network. A clear and trustworthy system of sharing information might help discourage the worst instincts of angry people.

* * * * * * *

(Golden Ball Tavern)

Adams’s fears are realized in Weston, colony of Massachusetts. Isaac Jones owns the Golden Ball tavern in the town. He’s known to be supportive of imperial rights and a critic of the tea protests. British Redcoat soldiers regularly stay overnight at the Golden Ball. Today, a group of tea protestors and colonial rights supporters have gathered outside Jones’s tavern and home. They shout at Jones to show himself. No answer. More shouts. No answer. Enraged, the crowd crashed through the front door of the structure. They rampaged through the main floor. They hurled crockery against the walls and floor, the hardened clay smashed into a thousand pieces. Along a counter they spotted containers of alcohol. They drank the contents and shattered the glasses. Upstairs, barricaded in a bedroom, Mrs Jones clutched a baby in her arms and prayed for silence. The crowd soon tired of its work and left the ransacked Golden Ball.

They were volunteers, all.

Also

Parliament passes the Boston Port bill into law, awaiting the expected assent from George III. The port will now be closed and all traffic diverted to other nearby ports. In addition, debate begins in the House of Lords and the House of Commons as to the need for fundamental reform of governmental practices in the colony of Massachusetts. Debate revolves around the use of town-hall meetings, the lack of armed power available to the colony’s governor, and the allowance of judicial powers on a local level. Proponents of imperial authority spoke in harsh terms toward colonial protests and protestors. If colonial rights supporters could have heard the debates in real-time, they would have been stunned at the extent of severe change directed at their political culture.

* * * * * * *

(Catherine)

In Russia, nearly 15,000 men have joined with Emelyan Pugachev in resisting imperial rule by Catherine the Great. While Pugachev sinks further into alcoholism-based stupor and demands that his followers agree he was the resurrected Peter III, Empress Catherine begins setting aside more and more hours in her daily schedule to planning for ways to destroy Pugachev and his uprising. Recent reports that General Vasily Kar had failed in a military expedition against Pugachev confirmed that the challenge is significant.

* * * * * * *

(Louis XV)

In France, King Louis XV, in frail and failing health, has placed broad authority in his chancellor, Rene Maupeou. The chancellor has pursued governmental reform through the removal of local parlements and replaced them with monarch-appointed judges who, in theory, could be chosen for their professional and legal abilities. Maupeou also tried to overhaul the tax system to account for more proportional distributions. His reforms, however, were unpopular and were being dismissively labeled “Maupeou Parlements.”

* * * * * * *

Three monarchs, three empires, three nations and all writhing with inner strains and convulsions.

For You Now

(around the table)

You sit down at your next gathering of the club or the group. Conversation, perhaps some food and drink. You’re there with them for a reason. Catching up, learning what’s now, a thought or two on the time ahead. Together, a variety of things are possible, likely many more than you’d assume. Between now and next time, let’s keep an eye on these agreed-upon points.

We do it so often that we’re unaware of how special it is to come together as we choose and decide. We don’t know our own strength.

Time can turn, though, and make it a little harder, and then a lot harder. With pressures mounting, the club and group needs to know itself or believe that it does. The unknown spaces between us are increasingly assumed to be filled with dark substances that don’t hold up to friction. Doubt gets the nod of indictment and none of benefit.

Time(s) can still turn again, too, and the value of Tocqueville’s voluntary association may once more cast a brilliant light. The club and group that vanished becomes the club and group renewed and reimagined.

The thing will take time.

(Tocqueville)

Suggestion

(Your River)

Take a moment to consider: when you think of it from a civic standpoint, what is the health of your club-groups?