Americanism Redux

June 6, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Life has more than one level.

(a levels view)

Big and large, middle and medium, small and tiny. A hundred others, too.

From level to level, things can change. An outlook, an action, a decision, each varies as the levels vary.

It pays to know the level you’re seeing.

* * * * * * *

(Connecticut State House, a level in Hartford)

Today, June 6, 250 years ago, the legislature of the colony of Connecticut is doing more than embracing the idea of convening a general congress to consider responses to the Boston Port Act. The legislators in Hartford go further to become the first legislature to vote to empower the Committee of Correspondence to select the people to represent Connecticut at the gathering. The legislative vote stops there. Now what? Who should be selected? What instructions do they need? When and where is the meeting?

On a large-group level like this one, a single decision produces more questions.

* * * * * * *

(A county’s seat of government, Dumfries, in Prince George County, a level)

On the same day as the decision at Hartford, a group of people gather at the town of Dumfries, Prince George County, colony of Virginia. They’re having a meeting smaller in scale than the Connecticut legislature’s but bigger in intensity and specificity. They write and approve a set of six “Resolves”.

To start, they declare that taxation can only occur with consent of the people, a right given to them by the “Constitution”, a term they didn’t bother to explain or feel a need to explain. In addition, they recognize that Boston’s suffering is in “the common cause”, a phrase heard from elsewhere and inserted here. Also, since the legislature of Virginia has been disbanded by Governor Lord Dunmore, those people holding elected political offices in Dumfries and Prince George County will take over responsibility for all government locally. The newly constituted county government will begin an economic boycott of goods from Britain. The county’s judges will refuse to conduct any trials by jury as long as the Boston Port Act is in effect. Finally, as the sixth and last resolve, the written record of the Dumfries meeting will be sent to Philadelphia and Annapolis for publication in newspapers. All six Resolves written, all six Resolves approved.

Held and done on this county level, the meeting adjourns.

* * * * * * *

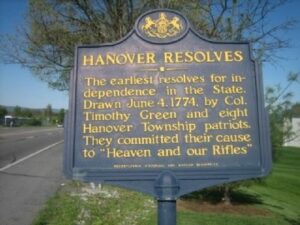

(Hanover, a town of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, a level)

Two days before the events at Hartford and Dumfries, the townspeople of Hanover in Lancaster County, colony of Pennsylvania, have formed a body called “the Associators”. They have taken on local military duties in a colony known for its official preference for Quaker pacificism. The Associators have boiled things down even further from the goings-on in Connecticut and Virginia. For them, the resistance and opposition to the Boston Port Act is all about this: “that in the event of Great Britain attempting to force unjust laws upon us by strength of arms, our cause we leave to Heaven and our rifles.” Done. Time to go home.

See you around town. That’s our level.

* * * * * * *

(the Parkman parsonage)

The Reverend Ebenezer Parkman of Westborough, colony of Massachusetts reaches for his Bible rather than his gun. He’s distraught over the rapid unraveling of well-being in Massachusetts caused by the Boston Port Act. With the imperial law now in force, “May God be pleased to Sanctifie this His holy dispensation of Providence to this whole People,” he writes. “I take,” he continues, “some special Notice of the sorrowful Frowns of Heaven upon the Land, and upon the metropolis of this province in particular, in solemn devotion.” Parkman knows that one of the biggest fears of the people in Boston is of “the (military) Forces expected to block them up.” Local myth and memory run deep about the evils of standing armies and a ruler’s paid killers.

* * * * * * *

(Greenough, he writes, not Greenwood)

When Nathaniel Greenough of Boston reads about the sympathetic and somewhat pro-imperial letters signed and sent to the hated ex-governor Thomas Hutchinson, he doesn’t reach for a gun or a Bible or anything else. Greenough’s first reaction is to grab a quill pen, scribble down a statement, and sprint down the street to the printers of the Boston Evening-Post. He asked them to publish his statement in today’s edition of June 6, 250 years ago. He declares to the public that one of the names signed at the bottom of the pro-Hutchinson letter was “Nathaniel Greenwood.” Nathaniel Greenough wants everyone in Boston to know Greenough is not Greenwood! That’s someone else, so don’t start yelling and screaming at the wrong man. And oh, by the way, Greenough’s store is selling a new round of “English goods, suited to the season.” Come early, buy often, heedless of the spending level.

* * * * * * *

(media coverage)

Greenough’s written plea for people to read the newspaper carefully is printed alongside articles, essays, and reactions to the Boston Port Act. The Evening-Post’s June 6 edition is stuffed with this material because readers are talking and thinking of little else at the level where daily living and the new law collide. The media coverage is nonstop and wall-to-wall.

Page 1 has a feature “Q-and-A” article about the Boston Port Act, ending with a call for an economic boycott of British goods (like those sold by Greenough). Another piece describes the recent death of Thomas Hollis in England, descendant of an ancestor known for resisting oppressive British rulers.

Page 2 includes “A Friend To Mankind” writing about the virtues of the recommended general congress as a “firm band of brothers”—a Shakespearean phrase that seems to be catching on—while residents of Marblehead have submitted an article denouncing fellow townsfolk for any part in the pro-Hutchinson letters. “A Countryman” writes from the Green Mountains to announce that he and other local landowners there will refuse to pay quitrents, or annual land fees, to British officials in support of Boston.

The June 6 edition of the newspaper is one of many signs of turmoil, shock, fear, and boldness in Boston and beyond.

* * * * * * *

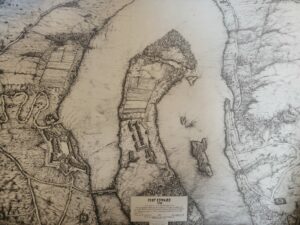

(Ft Edward)

John Cochran lives in the lakes-and-rivers region of the upper Hudson valley. He rents land to tenants near Saratoga, colony of New York, not far from an old, dilapidated British military post called Fort Edward, relic of the French and Indian War when the fighting was for the British King and British Nation.

Cochran is hesitating over his next move—to sell or not to sell? In his opinion “circumstances in the country have changed” and he can’t quite see his best course of action. He’s seeing immigrants from Scotland frequently moving into the area. He knows what he needs: insights from someone who understands the trend of factors affecting land prices. Such advisors and such advice are priceless in normal times.

And these aren’t normal times, which makes their worth even greater.

* * * * * * *

(Crown Point)

Further north in the same region, John Reid attempts to serve the role of advice-giver to newcomer Allan MacDonald. MacDonald is the leader of Scottish immigrants recently arrived at Crown Point, another decrepit British military post, this one located on northern Lake Champlain. Reid shares a range of advice about drawing on credit, finding farm tools, and acquiring weapons. He urges the Scottish immigrant to get his group of men, women, and children working together as quickly as possible. Identify the best hunters and fishermen in the group as well, he adds, so they can supplement food quickly during the summer months.

Reid warns about a particular threat—people from New England who might try to scare them off their land. Find the right balance between ignoring them as bullies and treating them kindly. Reid calls them “cowards” who are all show and no substance. He asserts that if they cause too much trouble, “Regular soldiers”, the Redcoats, can be called upon to keep order. Reid states that the “Yankees” view the Redcoats “with fear and dread.” The spector of Redcoats, Reid implies, will quiet them down.

These are the same military forces now re-locating to Boston to enforce the Boston Port Act and any other new imperial laws forthcoming.

* * * * * * *

So many levels, ranging from Hartford the colonial capitol, to Prince George the colonial county, to Hanover the colonial town to acreage near old British colonial forts.

Also

(their fear is he’ll live where he wants)

On June 2, King George III approves the Quartering Act, the fourth in the series of imperial laws designed to restore order in Boston and Massachusetts after the tea protests.

This new law is different in an important way.

The person serving as royal governor has new powers to ensure proper housing and logistical support for British military forces. The British military’s needs take first and overriding priority over everything else locally.

And here’s the thing:

It will apply everywhere in the American colonies, not only Boston and Massachusetts.

Yes, everywhere.

The British Army and Navy will get whatever it needs to be an effective force of enforcement. No questions asked. In a world where people are either living or fearing to live under new intrusive laws.

For You Now

(levels, a different view)

The levels tell their own stories.

Higher up, as with the Connecticut legislators, you see a collective decision to do something that looks a lot like themselves—convening in a congress to talk, think, negotiate. Go down the scale a bit and you see a sharpening and crystallization of action—the ideas that animate us and early steps taken based on the ideas. All the way down to the ground and the gain is in the simplicity and pinpoint of approach—pray and shoot.

If you try tracing a line to connect these levels, you’ll see surprising turns and not as much length and straightness as you’d expect.

Don’t forget the remarkable coincidence of two men separated by hundreds of miles and discussing separate issues referring to the same thing. Ebenezer Parkman near Boston comments on Bostonian fears about military enforcement while John Reid near Crown Point, New York comments about New Englanders’ fears of Redcoats.

That’s a sign of something that runs very, very deep in a collective attitude, identity, and mindset, a trait beyond the levels.

And they don’t even know about the Quartering Act yet.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: when you think of the American nation’s direction, is there a level of life you’re observing closely these days?

(Your River)