Americanism Redux

June 13, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

(within)

The deepest, inner-most workings of yourself are not where you spend every day. You can’t, it’s too exhausting. Those moments arise, however, when the depths, the core, the utter basics, are the only place for you to be to make sense of your existence.

Down there you’ll learn to flourish or to survive, to love or to hate, to embrace the greatest of all or endure the worst of everything. You’ll decide.

There are those days.

And weeks.

And months.

* * * * * * *

(Lucy)

The sound of her father’s angry words rang in her head. “No, not him, never him.” Lucy’s father, and mother too, opposed her choice of men to marry. They hated him, they hated who he was and the future he’d bring to their daughter.

Today, 250 years ago, 17-year old Lucy Flucker puts those words out of her mind. She plans for a secret wedding at the corner of King, Queen, and Cornhill Streets in Boston, colony of Massachusetts. That’s the spot where her future husband owns the “London Book-Shop”. In a small room above the books they’ll soon be wed against the bitterest objections of her England-loving family.

The London Book-Store is where they met. Lucy enjoyed Henry’s intellect and thirst for knowledge. Her parents despised what he read and talked endlessly about—military histories and military manuals that he sold to the public. They knew that Lucy and Henry were rabid supporters of colonial, American rights, and, truth be told, American independence.

Lucy knows that Henry’s reading differs from most people’s. He reads to do more than know or enjoy. Henry reads to apply, and he wants to apply his growing book-based knowledge of war and military affairs to the real-world life that unfolds every day with increasing darkness around the future Mr and Mrs Knox.

Lucy Flucker and Henry Knox are bound together by love and by a passion for the life they see coming. They desire to start their family in a new world free of stifling and frightening imperial authority. Lucy’s first break with authority will be with her own parents, who soon after today, 250 years ago, will disown her in a final blast of hateful words.

* * * * * * *

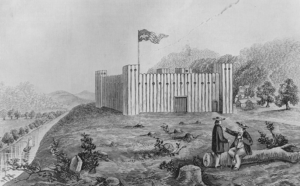

(walls where Betsy heard the sound, artist’s depiction of the event)

The sound of a hard thud (!) coming from the cabin walls. It’s the sound made when a Native warrior hurled an infant baby up against the rock-like wooden timbers. The baby, Betsy’s sibling, died in an instant.

Now a captive of Native Mingo warriors, 12-year old Betsy Spicer stumbles along a trail well-worn by animals and people. She sees endless woods, creeks, ridges, and ravines. She knows she’s nowhere near her home along Whiteley Creek, which flows into the Monongahela River north of Fort Pitt. She knows most of her family is dead, killed by Mingo warriors, revenge for the massacre of Natives perpetrated by Daniel Greathouse and many other land-hungry woodsmen from Virginia. She knows these warriors smashed the baby against the wall and tore the dress off her mother’s corpse. The sound from the wall and the sight of the dress will never leave Betsy.

Every next step is a willful act of Betsy’s life. Every prior step is a silent tribute to Betsy’s survival.

Above her, in the elm trees, the blue jays watch the group of rapidly moving Natives and captives. They fly from branch to branch, screeching and scolding as they go toward the waters of Beautiful River, O-ee-o.

* * * * * * *

(Fincastle)

South of the watchful blue jays, Captain William Crawford is on the junction made by Wheeling Creek flowing into the Ohio River. He’s supervising the completion of Fort Fincastle, built and named in honor of the governor of the colony of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, Viscount of Fincastle, the man who made Crawford a captain last month. Crawford and a hundred men rush to finish the project because reports of violence along the Ohio are spreading every day. Someone has said a family named Spicer was wiped out several days ago. Crawford responded by leading a party of men on horseback to warn white settlers up and down the river valley.

Crawford pays little attention to blue jays. It’s the vultures that catch his eye. He knows they may be circling the latest human body killed in the raging war. If it’s a white corpse, he’ll plan for revenge. If it’s a native corpse, he’ll plan for celebration. That’s been Crawford’s life since he first went into combat in this region back in ’55, in the French and Indian War.

Let’s get this fort done, Crawford tells his men, and we’ll plan our next move. Remember, we’re fighting to take this land for ourselves, Governor Dunmore, and Virginia.

* * * * * * *

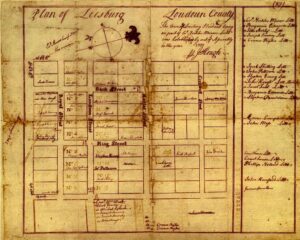

(early sketch of Leesburg, where the meeting will be)

240 miles east of Crawford and the nearly-finished Fort Fincastle is 40-year old Francis Peyton. He’s in Loudoun County in Governor Dunmore’s colony of Virginia and arranging last-minute details before he leaves home. Tomorrow is a special meeting called in Loudoun County to decide what to do in the worsening imperial-colonial situation. Peyton wants to leave things in order, including among the enslaved people living on his expansive farm.

Upwards of a dozen other counties are having versions of this meeting in the first half of June.

Peyton is a well-to-do planter who became a county judge and then one of the county’s elected representatives to the Virginia colonial legislature—which Governor Dunmore ordered to be dispersed, a series of events unknown to Crawford at Fort Fincastle on the Ohio River.

Peyton expects to be active in the upcoming event of “freeholders and other inhabitants.” He knows his neighbors; they’re eager to assert colonial rights, support Boston in its time of need, and roll back British encroachments on daily life and liberties.

But what of his contribution? What will the people there expect of him? Is his role to calm, or to inspire, or to guide, or to trail-blaze, or to analyze, or to…what?

And should he help the group align with the other dozen county meetings? With neighboring colonies? With colonies in far-away regions?

Answers don’t come quickly to such questions. You need time to explore deep within for a moment like this, time to sort through your abilities and experiences as a leader, what’s proven useful and what’s proven not. But for Francis Peyton, time seems scarce. The meeting is only hours away and monumental choices await.

* * * * * * *

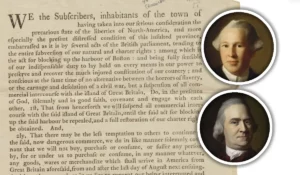

(a League sign-up sheet that set off the backlash)

Choices can be hard to make as the new reality of Parliamentary punishment begins to set in.

Boston’s turmoil spins around the “Solemn League and Covenant”. Using terminology of religious spirit, it’s designed by Samuel Adams, Thomas Young, and other members of the town’s Committee of Correspondence to impose and enforce a suspension of importation of goods from England and a potential economy-wide boycott of so-called luxury items as retaliation for the Boston Port Act. Violators—the people selling and using any good sent from Britain—would have their names printed in newspapers and, unstated but undeniable, likely the target of mob punishment, all at the behest of the Committee. So fierce are the counter-charges and accusations of neo-tyranny having moved from Parliament in London to the Committee in Boston that Samuel Adams adopts a new tactic. He convinces fellow members to soften the tone in public debates while restricting to private meetings their harsher rhetoric and plans for the League’s future power. Otherwise, the risk is real of being labeled the new bully next door.

On Philadelphia’s streets people are stalled in impasse. The town’s collection of artisans, craftsmen, and skilled workers feel a rising political power and want to help Boston through a vote held in a large public meeting. Blocking their path is the town’s existing culture that mixes Quaker theology and a merchant-flavored aristocracy. Also in their way are the Speaker of the Assembly, Joseph Galloway, and the colonial governor, John Penn, refuse to call for an official legislative gathering to consider options. George Clymer, a resident (and in two years a signer of the Declaration of Independence), notes a strong presence of self-interest in opposition to trade-based protests on behalf of Boston as well as a desire to achieve “Harmony and Perfect Unanimity” across the broader colonial response. Clymer detects an unreadiness in this community and surrounding colonies for a full plunge into the challenge and crisis. He predicts a new stage of intensity will be reached when all of Parliament’s laws go into effect and British Redcoats have been on the ground for a period. Clymer senses deeper dives ahead.

A basic human sympathy for likely suffering in Boston and Massachusetts marks the mood of southeastern New York and New Jersey. The feelings are one thing, the actions quite another. Beyond compassion, New York City’s residents are divided over the exact ways and pace for proceeding to respond to the current tensions via the colony’s legislature. James Kinsey, an elected legislator in New Jersey, expresses widespread opinion in the region when he states that rash action is bad action, doing nothing is unacceptable, and the best choices are a general congress producing a “United petition of the Colonies for Redress”.

* * * * * * *

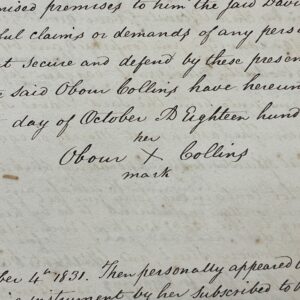

(Obour’s X, later in life)

Obour Tanner, a black woman in her early twenties, living in Newport, colony of Rhode Island, got good news today. Great news in fact, though, uh, not as great as it might have been. But still, a start is a start.

250 years ago today the legislature of the colony of Rhode Island approves a law opposed to enslavement.

“Whereas,” the law begins, “the inhabitants of America are generally engaged in the preservation of their own rights and liberties, among which, that of personal freedom must be considered as the greatest; as those who are desirous of enjoying all the advantages of liberty themselves, should be willing to extend personal liberty to others…in case any slave shall hereafter be brought in, he or she shall be, and are hereby, rendered immediately free, so far as respects personal freedom, and the enjoyment of private property, in the same manner as the native Indians.”

The less-than-great part of the new law are the sections after the preamble. Lawmakers tacked on a long list of exemptions allowing for enslavement and enslaved people to be in the colony. Enslavement will continue in the colony, together with change such as this law that gnaws at the practice around the edges. Continuity and change, together again.

First is first and this is the first such law enacted by an elected legislature in the British colonies. And it’s the first day of Obour Tanner’s life with this law on the books.

* * * * * * *

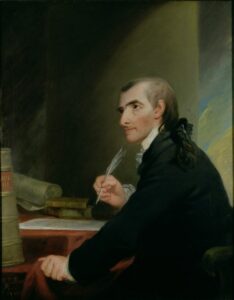

(parable author Francis Hopkinson)

Down the Atlantic Coast from Obour Tanner is Francis Hopkinson of New Castle, colony of Delaware. He writes a private story for his family’s use. It’s a parable, rather like some used by Jesus as recorded in the Gospels. Hopkinson (a future signer of the Declaration of Independence) creates a world where, a thousand years in the future, a father sends his sons away to live their lives. They prosper, but the father decides to tax one of the sons. The other sons oppose the tax on their brother but can’t agree on further action in resistance. The last line of Hopkinson’s family parable is this: “Harsh and unconstitutional proceedings irritated Jack and the other inhabitants of the new farm to such a degree that_____.”

That’s Hopkinson’s way of saying the future is unknowable, today, 250 years ago.

* * * * * * *

Blank lines are filled with the truths from the depths of life. Down deep they stay in silence, where existence lives before light, before surfacing.

Also

(George Bogle, after arriving)

George Bogle is 28 years old today, 250 years ago, and he’s on horseback in northeast India. In his possession is a document from the first Governor-General of the British East India Company, General Warren Hastings. Hastings has ordered Bogle, a Scotsman, to travel to Tibet to “open a mutual and equal communication of trade between the inhabitants of Bhutan (Tibet) and Bengal.” Bogle is to offer samples of British/Indian goods, collect information on local economic production, assess the roads and routes, and keep watch to secure particular breeds of cattle and pack horses along with rhubarb and ginsing. Oh, and art, don’t forget to grab any art that intrigues you.

* * * * * * *

(Spanish emissary, explorer, expeditionary)

Juan Jose Perez Hernandez is aboard a Spanish ship, technically a New Spanish ship because his origins of travel are in New Spain’s Mexico and California coasts. He is sailing north, passing along the rocky and forested coastline of modern-day Oregon of the Pacific Northwest. Like Bogle in India, Hernandez has orders; in his case, he is to establish a Spanish claim to the region before British and Russian explorers can prevent him from doing so.

* * * * * * *

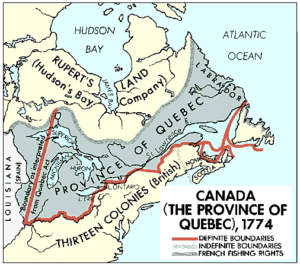

(the next change coming)

And in London, England, the British Parliament is in the final stages of debating the Quebec Act. The Act will expand the boundaries of Quebec or New France, now a British province after the French and Indian War, into the south and western areas of the Great Lakes region. Roman Catholicism will be extended throughout the area, British civil law will be the norm along with an allowance of some Canadian legal customs, and the French system of land ownership will be restored. Viewed as enlightened by many, it will also be perceived as cynical by some in light of its chess-like countermovement against the British colonies and their westward ambitions. Those in Protestant New England will see it as an endorsement of Catholicism and, worse in their minds, popery.

For You Now

(trio)

Three young women form a special trio for us today. They are Lucy Flucker, Betsy Spicer, and Obour Tanner. Everything that goes into today’s stories, from imperial-colonial relations to daily life, swirls around them.

Lucy makes a decision on her future. It will alter the course of her life.

Betsy copes with a decision—including an impulse of unfathomable violence—that others have made. Her life will never be the same.

Obour also copes with decisions that others have made. The difference for her is that a new decision has come along that has the potential to shift the direction of her life.

In each case the need arises for a person to probe her (or his) own basic ability to live, to exist, to be human.

Around them are laws, meetings, speeches, documents, and the doings of people in various positions and vantage points. Each of them and all of them can be adapted for insertion into blank space left at the end of the last line in Francis Hopkinson’s family parable.

Will the American Revolution provide them with the words they need?

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: what do you want people with a grievance to do?

(Your River)