Americanism Redux

July 11, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Endcoming.

Is this a new word? Could be. The definition: an end that you see coming.

The now won’t last. The way you’re used to? It will be over. No doubt about it.

A profound change will set in. It’s only a question of when and where and maybe not much of a question at that. Don’t waste time wondering whether it will.

It will. Of course, it will. Not endtimes or anything like that. But something else. You’ll know exactly what I mean when you see it. Maybe you already see it and already know it.

Endcoming.

* * * * * * *

The body on the bed was once a life. That life influenced British settlers and Native tribe members across a large stretch of the central region of New York colony. That life claimed ownership of thousands of acres, lived in a wondrous house, led British soldiers and Native warriors in battle, and negotiated trade deals and land deals that kept British and Native interests in reasonable harmony and connection. That life was called Sir William Johnson, First Baronet. Life left Johnson’s body earlier today, 250 years ago.

Beside the bed is the inheritor of everything, including the title “Sir”. John Johnson is 32-years old, the only offspring of his mother and father’s common-law and unchurched marriage. John was already walking his father’s path in taking a common-law wife, a relationship he had ended not long ago. John had quickly re-married—formally, legally, religiously—this time to Mary Watts, whose father is an avowed supporter of the British Crown and the appointed leader of New York’s King’s Council.

There are more of father’s footsteps to follow for John. His dead father had affected the lives of individuals, families, farms, and villages from both the British and Native worlds. Makers of military strategy and economic networks had paid attention to his father’s opinions. People with massive egos and touchy pride had been soothed by his father’s words. The eastern Great Lakes and St Lawrence River valley alike bore the imprint of the once-living body stretched on the bed. In this region, where the dead body on the bed defined a large part of the era, the endcoming is here.

Sir John Johnson will start tomorrow as the new occupant and owner of Johnson Hall, built by his father next to Hall Creek, with the Adirondack Mountains a few miles to the northwest. Everyone who meets Sir John will wonder how, and if, he measures up. What follows the endcoming?

* * * * * * *

(Occom)

Samson Occom enjoys something of a day off today. He doesn’t have to strain his voice to be heard. He won’t have to exhaust himself in preaching, praying out loud, and keeping aware of who is listening to him, who is tuning him out, and how to capture the attention of the inattentive. Those three sermons yesterday left him worn out.

Today, this evangelist Mohegan Native is still in Farmington, colony of Connecticut, still spending time with his fellow Mohegan Native tribal members. He is away from yesterday’s pulpits and has “all Day, visited amongst them (and) found them well in general and well Disposed toward Religion.”

Occom greets them during these hours. They smile and take some moments to talk with him about their families and themselves. He smiles back and nods, gently slipping in his descriptions of the main points of the Bible, especially Jesus Christ. He answers their questions and listens to their reactions.

Person by person, each is an encounter, some are relationships, and in the brevity of such stops that comprise his longer journey, all are endcoming.

It will be onward again, further north and west into the Connecticut River valley, town to town, pulpit to pulpit, Native to Native.

* * * * * * *

(Paterson)

Along Occom’s planned route is an ancient mountain range slightly west of the Connecticut River. The range runs through the county of the same name, Berkshire, located in the colony of Massachusetts. Lenox is a small town in the county. John Paterson is one of Lenox’s newest residents, born in Farmington, Connecticut where Samson Occom is today resting up from his three sermons.

Paterson is 30 years old. He and Elizabeth have three children. They had left Connecticut, their colony of birth, and relocated to Berkshire County. Berkshire’s residents tended to regard themselves as separate from everyone else.

The Paterson’s move felt like an endcoming.

They’ve had a new endcoming.

John is back today with Elizabeth and the kids from a meeting three days ago held elsewhere in Berkshire County, at Stockbridge, a town known for a Native school and church. The meeting was the endcoming.

Prior to it, no county in Massachusetts had ever organized representatives from every local town for a county-wide convention about the imperial-colonial crisis. None. Now, there was one and the precedent was set.

At the Stockbridge convention Paterson and a group of sixty men voted to adopt Boston’s “Solemn League and Covenant”. The League is an aggressive model of action, designed to identify and punish people who refused to ban British goods and luxury items in counter-protest of British imperial policies. The League has proven divisive in the port of Boston but not in the county of Berkshire. The group of sixty is ready for it and with the county-wide convention voting yes, the muscle is there.

Endcoming.

* * * * * * *

(scene of the Essex County meeting)

As the Patersons gather at their Berkshire home, William Young in Virginia massages his aching hand. He’s been the clerk at a meeting of “the freeholders and other inhabitants”—note the two separated terms and the absence of the word “towns”—from Virginia’s Essex County. In less than a day at a county-wide event, participants have endorsed seventeen different pro-protest and pro-Boston resolutions. Yes, seventeen in a few hours. The math suggests most of the resolutions were haggled over, written, and approved beforehand. Clerk William Young scribbled everything down furiously for the formal record at the meeting.

Burrow into Young’s pages and interesting points emerge. First, the resolutions refer constantly to “it is the opinion of this meeting…”. The phrase hints of flexibility, pliability, adaptability. Second, a new aspect of economic reality appears; if British goods are boycotted and banned, then the door opens for local producers to raise prices. That must be avoided in the “opinion of this meeting.” Also in the economic realm, debt collection through civil courts by British creditors should be halted. Third, there is one “great law of nature” articulated: “the principles of self-preservation”. It is fundamental to everything else.

Maybe it’s not surprising given the fact that beginning six weeks ago Virginia was the fountainhead of support for Boston and Massachusetts. When self-preservation is part of opinion, an endcoming of imperial-colonial relations has been reached and something different is about to appear.

* * * * * * *

(Parkman’s house)

Samuel Parkman, a well-to-do preacher’s son, writes from his house in the epicenter of crisis called Boston. His location is Merchant’s Row near Fanueil Hall. He’s trying to deflect all the noise and fury and forecast into a near-term future. He starts with an acknowledgment that Boston and other towns haven’t “conformed” to the governor’s dismissal of the Massachusetts legislature. From there, he peeks out, noting people “expected there would be a Congress”, which is now coming to fruition. A deep breath follows. The Congress will meet, decide, and “pursue the Measures that would be agreed upon by that Body.” There, whew, said in such a manner, Parkman’s assumption is of a change for the better. Zip, whoosh, done. Wind turns to breeze when you hear a rhythm in the noise. Endcomings are homecomings.

* * * * * * *

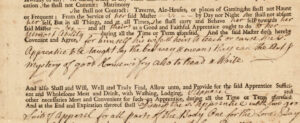

(the Overseers’ document)

A short distance from Merchant’s Row is a young boy named Robert Burgain. He’s had an endcoming this week, a definite point at which what he’s always known will be no longer and what he’s never known will become true. In a process monitored by Boston’s “Overseers of the Poor”, Robert is leaving his family to live for four years as an apprentice with Benjamin and Martha Eddy. This “poor child”, as he’s called, will learn the skill of maritime navigation along with reading, writing, and basic math. In addition to the knowledge, he’ll get “Two good Suits of Wearing Apparel for all parts of his Body, one for Lord’s Days and the other for Working Days, Suitable to his Degree.” These are the promises written on the paper that the adults hand back and forth to each other.

Who will see that the agreement holds up? Maybe the Overseers, maybe two judges who add their signatures to the document, maybe two witnesses standing close by. Or maybe it all depends on the Eddys and Robert.

Endcomings are hazy on enforcement.

* * * * * * *

(John Floyd)

During his endcoming of a few weeks John Floyd has aged several years.

Most of the young men with him left when news arrived that the Native Shawnee tribe was at war with the colony of Virginia. They grabbed canoes and left down the Ohio River to the Mississippi River. Two of his men have been killed by Shawnee warriors.

Floyd has kept a handful with him, determined to stay on and do the job of surveying that brought him here to Kain-tuck-ee. He’s notching trees and laying markers along the Elk Horn and Bear Grass Creeks a few days’ hike south of the Ohio River. Seven thousand acres for Patrick Henry, eight thousand for Colonel William Christian, three thousand for Alexander Dandridge, one thousand for himself, and some others.

Today, though, there’s a happy break in the worry. He’s sitting next to a large spring of fresh water, one of the largest he’s ever seen. Give it a name. Only one seems right after all the trouble these past weeks: Floyd’s Spring. Nothing like cool, chilled water, down your throat, soaking your face, from your self-named spring, as the locusts whine on a hot summer day.

Did you see something move over there, past the tree line?

Let’s finish up. In a few days, we’re heading back east, back to Virginia, as fast as we can.

* * * * * * *

Also

(Pasha is left)

Light-headed, his body unresponsive to what remains of his conscious thought, and then…collapse. Has his life ended? Guards carry the still-breathing body of Muhsinzade Mehmed Pasha from a small building in the village of Kucik-Kaynacarca (in modern Bulgaria).

The strain of defeat was too much, the burden of humiliation too heavy. His duty up to today, 250 years ago, was to serve as the primary treaty negotiator for Abdul Hamid I, Ottoman ruler for the past six months. There’s not much negotiating to be done, however, and that’s the problem. The Ottoman Empire is now surrendering to the Russian Empire after six long, bloody years of war. He had signed the treaty signed hours ago in this small community of a hundred people along the bleak, rocky banks of Tohma Stream with Russian officials eyeing him closely.

No one knows if Muhsinzade Mehmed Pasha will survive. No one knows yet of the massive shocks about to begin in the Ottoman Empire because of the treaty bearing his imprint. Russia now gains control of Romanian land and the Crimea Khanate, once belonging to the Ottomans. Russian officials can begin building a Greek Christian Orthodox church in Constantinople (Istanbul), unleashing pent-up Greek Christian Orthodox influence across the Ottoman capital city and beyond. The Russian reach will extend into the Ottoman Empire toward the Black Sea. Marked nearly by the weeks and months on the calendar, the vibrancy of the Ottomans starts a rapid descent.

The condition of Muhsinzade Mehmed Pasha is little changed today. His breathing is weak. He’ll be transported back to Constantinople on a stretcher. His wife Esma Sultan will be horrified by what she sees.

He’s at the endcoming. He’ll live for less than a month more, losing a life spent in the ranks of government and military within the Ottoman Empire.

* * * * * * *

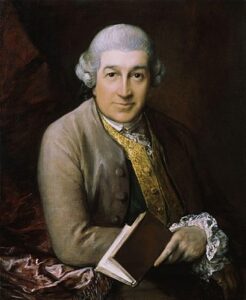

(the actor posing)

David Garrick is perhaps the most famous actor in England, today, 250 years ago, one of the most famous of his generation. He’s written a brief, one-man comedy skit to be performed on stage, an opening act for some longer, main-feature show. Garrick thinks the public mood is anxious and dark at the present moment and more laughter and humor should be available to the public. Hence, his skit entitled “Prologue” and delivered at a theater last night before the start of a play called “Couzens”.

A critic, though, didn’t like Prologue and wrote a negative review of it in a London newspaper.

The review outrages Garrick, who calls it “an impudent lying paragraph”. In retaliation, Garrick starts writing another skit another such act for performance later this month. He has decided his target: critics. He will make them the butt of every joke and the ass of every jab in this new show-opener. After the endcoming, the critics will leave him alone.

* * * * * * *

(modern Thurnscoe)

“In whatever things are lovely and of a good report,…”

They were Reverend John Green’s favorite words from the Bible and in his voice they will never be heard again. Yesterday, at Thurnscoe of Yorkshire in England, he died.

The same day, Sarah and John Detlaf leave London on a ship bound for the colony of South Carolina. John’s a tailor and together they seek a new life.

* * * * * * *

The endcoming is the turn from what you’ve known and done to something new and undone up to now.

For You Now

(the past road imagined)

The story of the American Revolution is so well-known that we forget that it was a day-by-day experience. 250 years ago today each word in that title—American, Revolution—is up for grabs, undecided, of traces without facts. And yet, we read the title cruising on a path traveled frequently, with the rough made smooth and the jagged made straight. Color and motion belong somewhere else. You can sip from a glass and not spill a drop.

Endcoming is a way to rip up the road, restore the living, and forestall the remembering. Ruts bounce you from side to side. Crookedness forces you to leave the seat and start chopping up the fallen branches. Downhill brings a speed you may not want that always weakens. Uphill slows you to an undesirable crawl on fuel that always depletes. When the storms come, the water splashes inside.

A reader can rightly ask me, “Isn’t everything potentially an endcoming as you’ve defined it?”

Absolutely, yes.

The control you’re able to find comes only from a connection between your internal self and your external meaning. That will help length become distance, motion become direction, and movement become journey. The coherence you assign to the past will feel more frequent in reality.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: where are our opinions rooted today? Where is their source? Recall that in Essex County, “the opinion of the meeting” was in the one great natural law, self-preservation and the principles flowing from it.

(roots on Your River)