Americanism Redux

January 24, Your Today, 250 Years Ago, In 1775

Two tracks, two lines, two paths.

For now, they are apart. They run separate. Day by day, though, they come closer together. They’ll touch, join, blend. What happens then?

Something will change. One of them will change.

* * * * * * *

(look for the Phillips family)

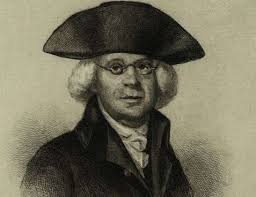

William Phillips is a merchant in Boston, colony of Massachusetts. 53 years old, he has been a stalwart supporter of colonial rights. He’s been at the forefront of meetings, debates, and discussions. He’s cast votes in decisions and signed signatures on resolutions.

He walks the cobblestone streets of his beloved town and sees nothing but misery. The Coercive Acts seem to be strangling the place, a slow death by choking off community lifeblood and individual livelihoods.

Today, 250 years ago, Phillips walks into his home on Beacon Street. There, with his wife Abigail and their two children, he holds a single thought in his head. He sees Abby, and then William, named after himself and daughter Abigail, named after his wife. The children’s names reveal the family’s culture of symmetry, order, and balance. The family likes it when the world fits together.

So it’s all the more jarring when William Sr reveals the thought in his mind: “A Storm seems to be gathering by the conduct of some of the Officers of the (British) Army towards the inhabitants.”

Storms and order misfit. Those lines don’t blend.

* * * * * * *

(Thomas Johnson)

Thomas and Ann Johnson live with their seven children in Annapolis, colony of Maryland. They’ve worked hard as husband-and-wife to build wealth for their family. For the past eight years they’ve been steady supporters of colonial rights, especially as related to their home colony of Maryland. They’ve been vocal and involved. Now, however, they’re thinking more about how Maryland connects to other colonies, Massachusetts foremost among them. Their views of the world have widened.

The Johnson family is examining a new investment opportunity. It’s in western Virginia, the acreage along the upper Potomac River. The Johnsons believe that the Virginia legislature needs to invest in clearing the navigation of the Potomac River further inland. But the current crisis between the British Empire and British colonies have gummed up the works, derailing any chance to spend money to improve western access via the Potomac River. So, the Johnsons are holding off on any investment in land purchases. As Thomas Johnson says, in this political environment everyone wants to borrow but no one wants to lend.

* * * * * * *

(a heating-up commodity)

Military consultant Charles Lee continues to advocate for his plan for military organization in Maryland. If supporters for colonial rights in Maryland can finally be persuaded to adopt Lee’s plan, it will give legitimacy and influence to Lee, the former officer in the British Army who served in the French and Indian War. He might then translate that new-found prestige into further power with other colonial governments. As the threat of war grows and crystallizes, a leader with perceived military ability will gain in stature and authority.

If war is reality, Charles Lee strides forward.

* * * * * * *

(nephew and uncle are here)

John Benezet is one of 81 delegates starting a meeting in Philadelphia, colony of Pennsylvania, today 250 years ago.

The group sits down to hammer out their position, approach, and strategy for the current crisis between the British colonies and British imperial government. They’ll likely be here a few days. The meetings will be intense.

Benezet is a Quaker, nephew to one of the most influential Quakers in the colonies, Anthony Benezet. As Quakers, John and his uncle are struggling to walk a line so thin that it’s nearly impossible to see. They want to support colonial rights through “lawful action” without descending into violence. The economic boycott of British goods and services now underway is about as far as they’re willing to go.

Yet even the boycott has implications that run much farther than might have been anticipated. Quakers like John and Anthony Benezet are now beginning to explore how to overturn the nature of Pennsylvania’s economy to make it self-sufficient and self-contained—to slash economic ties abroad and stimulate local production of everything from sheep to nails, from barley to copper kettles.

War is not the only whirlwind tearing at the roots of economic life in Pennsylvania.

* * * * * * *

(thanked for before and chosen for next)

Stephen Crane is in Trenton, colony of New Jersey, seated in his chair and listening to Quaker members of the New Jersey Assembly express their belief in peaceful protest and change.

Crane’s a veteran of the Continental Congress that met last fall, one of the delegates from New Jersey. He’s upset at knowing the Quakers will not approve participation in the next Continental Congress planned for May in Philadelphia. To them, a second Congress likely will mean a step closer to war. They want nothing to do with violence.

Crane stays in his chair as the Assembly takes up two separate votes. The first is to thank Crane and his fellow delegates who represented the colony last fall in Philadelphia. A majority say “aye”. The second is to choose the same team of representatives, Crane included, to return to a second “Congress” in the spring to tackle whatever form the crisis has taken. Again, the majority say “aye”.

Crane shifts in his chair, wondering about the future. Four months from now seems like a long time. He can’t know if the spring will change the proportions of supporters, opponents, and neutrals in his native New Jersey, though he’s certain the Quakers won’t budge.

He also can’t know that four generations from now, his great-great grandson will be born, the author of “Red Badge of Courage”.

* * * * * * *

(at Cartright’s)

These meetings are everywhere! In the county of Albany in the colony of New York, Abraham Yates Jr calls a group of people to order in Cartright’s Tavern. They’re seated around stout wooden tables with tankards of ale and cups of hard cider. In between sips and slurps, the topic they’re chewing on is the organization of a New York provincial convention. The goal is to produce a new legislature that is aligned with last fall’s Congress in Philadelphia and the next one coming in spring.

Yates’s meeting at Cartright Tavern is the first of several popping up across Albany County and other sections of the colony of New York. Like the Yates meeting, they’ll have attendees, factions, arguments, understandings, misunderstandings, debates, and resolutions. These meetings are the furtherance of gatherings that have occurred over the past seven months.

* * * * * * *

(a later version of the early man)

These are the days of days for John Adams, of Braintree in the colony of Massachusetts. The lawyer and relentless supporter of the colonial cause writes a letter that he dispatches on a boat sailing to London, England. It’s his hope that the letter will find its way into print in a British newspaper operated by a colonial sympathizer. Likely it will.

In the letter Adams is at his best, full of blistering heat and dazzling clarity. He states that the answer to the current crisis is so very easy to see—a return to the imperial/colonial status of 1763 when British authority largely left the British colonists to themselves. To do otherwise, to force 3,000,000 people 3000 miles away to do the bidding of a central power is insanity. And to do so while the central power sinks in debt is madness multiplied.

Adams celebrates the success thus far of 3,000,000 “free white people” in setting their own course. In Massachusetts, he declares, “four hundred thousand people are in a state of nature, and yet as still and peaceable at present as ever they were when government was in full vigour…The town of Boston is a spectacle worthy of the attention of a deity, suffering amazing distress, yet determined to endure as much as human nature can, rather than betray America and posterity.” Some thirty years ago a similar sort of public spirit prevailed during a previous war where everyone British fought side-by-side, Adams recalls, “but I remember nothing like what I have seen these six months past.”

Adams turns from writing his letter to writing the first installment of what he suspects will be a series of public essays printed here in Boston. He adopts the name of “Novanglus” to blast out a ferocious written response to the pro-imperial author known as “Massachusettensis”, actually a close friend and fellow lawyer, Daniel Leonard.

Adams begins this opening performance as Novanglus by attacking the ability and credibility of Massachusettensis’s logic. Next, Novanglus writes of the “revolution-principles” of “Aristotle and Plato, of Livy and Cicero, of Sydney, Harrington, and Locke”. They wrote of ancient virtues that current Bostonians are putting into practice resisting the Coercive Acts, here and now. “If they die, they cannot said to lose, for death is better than slavery. If they succeed, their gains are immense. They preserve their liberties.”

John Adams roars into the wintry night, his ideas and attitudes spanning the cold Atlantic Ocean.

Also

(Pittsburgh’s name-origin)

He was a hero, his praises sung. They loved him in those prior days of the old war. Statues were made to honor him. Forts and towns were named to revere him. He was William Pitt, of the House of Commons and a key member of George II and George III’s inner circles during the French and Indian War of 1754-1763. The colonists in America loved the man because he saw worth in them.

A few days ago, sporting a newer name of Earl of Chatham, elevated in rank and status to membership in the House of Lords, ill and feeble, he stood up in Parliament and spoke on behalf of the colonists. Through wheezing breaths he urged his fellow politicians to recall the British Redcoats stationed in Boston with General Thomas Gage. With a gaunt face he spun sentences and delivered oral flourishes to persuade his political audience.

It was all to no avail. The final vote revealed only one of every nine men in the House of Lords expressing for his proposal. Stopped, denied, defeated.

Today, 250 years ago, the weakening Earl of Chatham is still recovering from the exertion of his desperate plea.

For You Now

(lawmaking)

Go back to my introduction of today’s Redux. Two lines. We’re seeing one very bright line today, the same we’ve been seeing for weeks and weeks. It’s the line of legislating, of (new word alert)…legislaturing. Of law, of legis, as the Romans wrote it.

John Adams is one of its creations. The recurring action of convening people in a legislative setting, placing them in a legislative posture, invoking their legislative skills continues today. Adams shares arguments and insights in writing that he’s developed and refined in countless meetings and dialogues. They’ve been used to produce resolutions and written statements. Adams and hundreds of other pro-colonial rights supporters up and down the Atlantic coast have Assembled and from Assemblies stated their points and built their cases.

The leadership and the collective culture of a legislature and assembly are unique. And that’s what has been promoted, elevated, rewarded.

Small wonder, then, that for an American Union which is also in creation, the legislative molecule fills up the DNA strand. The public legislature and civic assembly is everywhere on the strand of Continental Americanism. Lay bare the surface and pull back the skin and you’ll see it sparkling, a defining life force. It’s why about a dozen years into the future (1787), the draft Constitution will emerge as a legislature-first document structure.

But at the moment in 1775, the prospect of war that William Phillips has crystallized for us in today’s Redux could change all that and will certainly affect all that, as people like Charles Lee can demonstrate.

Wars are a group enterprise but not a group endeavor. They give rise to solo commanders, to executives, and in the same dozen-year time span forward, to an Executive Branch with the responsibility for war-waging. Legislatures legislate. Executives execute. War resets the balance.

Thus, 250 years ago today, one line is plainly visible and alive. A second line is coming into view and gaining an ability to live. At this rate and at some point, the balance changes.

(empty for now)

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: in today’s moment, is the balance rebalancing?

(Your River–not the same after the coming-together, like the OH and MS)