Americanism Redux

February 20, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1775

(microscopic)

Sometimes you don’t know until you look closer. Really close. When you do, you’ll often see things that are, up to that point, unseen. So it is with this.

A very close look and it becomes clearer—seventeen months before anyone declared any nation independent, the British colonies had formed into a union.

That Union is of themselves, those people in each colony who believe and know it is true.

Today, 250 years ago.

* * * * * * *

(notice the left hand)

The Second Provincial Assembly in the colony of Massachusetts is functioning, fundamentally, as an elected body of revolution. They have voted earlier this week that “we are convinced that the union now established throughout the several Colonies” demands constant communication.

The Committee of Correspondence, first organized two years ago, will see to it that such communication occurs. It’s a duty to the union.

* * * * * * *

(one of the members)

Joseph Warren, a Provincial Assembly member, beams with confidence in the gray light of the Massachusetts winter. He expects a triggering event by the Redcoats any week now, and “I trust the event, which I confess I think is near at hand, will confound our enemies and rejoice those who wish well to us.”

“I am of the opinion that if once General Gage should lead his Troops into the countryside, with a design to enforce the late Acts of Parliament, Great Britain may take her leave, at least of the New England colonies and, if I mistake not, of all America.”

Today, Warren is exuberantly pro-Union, the real government of the here-and-now colony of Massachusetts.

* * * * * * *

(another of the members)

Another member of that same Provincial Assembly is John Adams. Today, he’s publishing in a newspaper the fifth installment of his fake-named Novanglus essays, his series of rebuttals to the pro-imperial rights writer, Massachusettensis (his close friend, Daniel Leonard).

Adams writes of the virtues of ordinary people voting on issues basic and important in their lives, of the workable existence of “three branches” of the government, of the destructiveness of elected officials who have evolved into corruptive and power-hungry officeholders. He reconstructs how ten years of problems and wrong-doing have led to today’s revolutionary situation. He seeks to put into context the occasional violence and disorder that have occurred.

For him, the Union is succeeding.

* * * * * * *

(ground level)

On the ground in the Union operating for Warren, Adams, and 300,000 residents of Massachusetts, two conditions have emerged.

First, one of every five people in Boston (15,000 population) is living one meal at a time. They lack food and other necessities of life because of the British blockade of the port of Boston. The only thing preventing public starvation is a stream of donations from supporters of colonial rights who live in other colonies and communities. Churches have been especially vital in food donations. A government-organized entity has been managing the flow of food to the needy.

Second, it’s reported that the “propertied class” of Boston and surrounding communities are strictly opposed to starting a tax that will provide revenue to pay for military forces that would resist British Redcoats. Rumors are everywhere that anyone who pays such a public levy would be subject to property confiscation by British General Thomas Gage and his armed forces.

How the young Union can respond to such challenges isn’t immediately clear.

* * * * * * *

(their majority says ‘no’)

The New York Assembly has voted NOT to thank the colony’s delegates who participated in last fall’s special Congress in Philadelphia. It’s a solid majority that wishes to express its dissatisfaction with the economic boycott and the rest of the pro-colonial rights program.

* * * * * * *

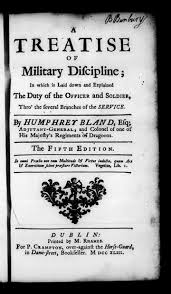

(popular book)

Organized units of volunteer militias in the colonies of Virginia, Maryland, and the three Delaware River counties that comprise Delaware are reading and practicing how to load, fire, march, and maneuver as soldiers. Humphrey Bland’s “A Treatise of Military Discipline” is the standard resource book for the county-based units in the three colonies. They convene at least once a week and often more frequently to master the training.

Separately, sixty miles north of Philadelphia, gunsmith Johann Christian Oerter in Bucks County, colony of Pennsylvania is a popular craftsman today, 250 years ago. A Moravian immigrant, Oerter makes by hand a “long rifle” that is elegant and deadly at the same time. A man skilled in the use of the rifles can load as often as twice per minute (though once is more likely) and hit a small target 250 yards away. Oerter will need a week to make a rifle to your order. But the backlog is great and growing, a result of rising demand.

Most of the volunteer militia are using muskets, not rifles, and because the interior of the gun barrel is smooth and not spiral-tracked like the rifle, the best range is sixty yards.

* * * * * * *

(Stephen)

Some of the most skilled riflemen served with Adam Stephen in the recent Virginia-sponsored military expedition that seized Native lands along the Upper Ohio River. Stephen is writing Virginia’s Assembly to urge them to make immediate payment to those soldiers who served in the expedition. Stephen’s advice is that these are unpredictable times and the abilities of men who know how to fight could again prove useful very soon.

Many of the men who served with Stephen are of a decidedly different background and lifestyle than those training with Bland’s manual.

Everyone knows the subtext of what Stephen is insinuating.

* * * * * * *

(the county in yellow)

In Virginia’s Hanover County, a meeting of delegates chosen by residents has agreed to recommend a poll tax to pay for the soldiers who served in the expedition along the Ohio River, the war called Lord Dunmore’s, named after the colony’s imperial governor.

It’s another example of a simmering issue plopped in the laps of a colonial assembly governing in the fog of winter, of an ended war, of steaming-hot tensions that might boil over in New England and pour down to the Chesapeake Bay.

* * * * * * *

(a quaint place in Bethel)

Nicholas and Henry Davies are bullish on the future. The father-and-son team have laid out the plans of a new town, Bethel, west along the James River, in Amherst County, below “the great mountains.” The prospects are good for reasonable access to numerous grains, beef, and pork. To have a viable community, the Davies men are hoping for a blacksmith, a shoemaker, a weaver, a cabinetmaker, a cutler, and a wheelwright to purchase or rent land from them. Also, if anyone has a talent at mining, Bethel could be an ideal location—a chance to strike gold, if you will—as deposits of tin, lead, and copper are nearby. Or if your gifts run to brewing, linen-production, or rope-making, a factory can be built to crank out the profits.

Get to Williamsburg, colony of Virginia as soon as possible and ask for the Davies father-son duo. Take the first step toward a new future.

When you think about it for today, 250 years ago, Nicholas and Henry Davies are issuing a call first heard in this region, at a place called Roanoke. Join with us, go with us, claim with us a new beginning.

It’s a call that’s been sounding ever since.

* * * * * * *

The new beginning is unfolding in a way no one predicted. Not only is the beginning in a place, but also in a union of places. Not only in a life where a few have banded together, but also in a world where the bands have bonded together, making a new whole.

Also

(North)

The label is “conciliatory”. It’s a conciliatory speech and offer and proposal. Lord North, prime minister of George III in the House of Commons and Parliament, has brought forth a plan to ease imperial-colonial tensions. To North’s way of thinking, as well as that of Parliament’s majority and the King himself, the possibilities are bright.

Boiled down, here it is:

The British imperial government pledges not to seek further revenue from the British colonies if said colonies, singularly and separately as entities, will agree to raise a share of the cost of common defense and of the support of local government.

There you go.

* * * * * * *

(Johnson)

The influential writer, critic, and commentator Dr. Samuel Johnson has published what many have been waiting for—his public analysis of the current imperial-colonial crisis. It’s entitled “Taxation Not Tyranny”.

In it Johnson supports existing British policy and rejects colonial arguments in favor of political change. Johnson lampoons colonial logic as equivalent to having the community of Cornwall seek imperial reform. He blasts the colonists for simply doing everything they can to pay taxes and notes, with dripping sarcasm, that they don’t seem equally motivated to address enslavement as a problem.

Johnson’s essay is another tool that Lord North can use in defending the imperial approach, even if the essay’s author would oppose the “conciliatory” strategy now adopted by a vote of 274-88 in the House of Commons.

* * * * * * *

(de Vegobre as an older man)

23-year old Louis de Vegobre lives in Geneva, Switzerland. He’s been teaching and learning at the same time. The teaching: he teaches math to John Laurens, visitor from the colony of South Carolina. The learning: Laurens teaches him about the imperial-colonial dispute.

De Vegobre is all on fire now for colonial rights, though he’s never been to the New World. He’s also passionate about his friendship with Laurens, who has left Geneva.

De Vegobre has written two letters to Laurens with no reply. Is a third time too much? Is it over-the-top? How far do you push communication in a friendship?

Can a relationship survive the distance?

It’s a question between friends like it’s a question between parts of an empire.

For You Now

We were a Union before we were a Nation.

Abraham Lincoln asserted this, and so do I. My work in Redux has shown the total accuracy of the point.

What isn’t as easily shown, because it’s gotten even less thought and attention than the fact of Union itself, is the implication of the point.

I think we should do much, much more to better understand the significance of Union First/Nation Second.

You can see the through-line from 1774-1775 to Lincoln and the Civil War of 1861-1865. There’s a reason Lincoln’s military was called the “Union” Army during the conflict. It’s further reason why the oppposing force was rightfully the “Confederate” Army. It was more than the fact that the opposing army fought on behalf of the Confederate States of America. It goes to the heart of the truth that Lincoln’s military was the Union-ized Army, perhaps more accurately than the “United” States Army.

We’ve lost hold of the lessons that can be gained from knowing that the Union was alive and alert in early 1775, before actual extensive bloodshed at Lexington and Concord and well before the Declaration of Independence.

The Union needs to stand on its own, teetering and hesitant though it is, before the Nation can exist. The Union feels its flesh and bones, before the Nation can continue. The Union takes its first shaky steps, before the Nation can endure.

The reality of today, 250 years ago, is the reality of Union-izing.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider this: what’s the difference between a Union and a Nation?

(Your River)