Americanism Redux

December 19, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

The storm’s not on the horizon/

The storm is not out there/

The storm that’s now arising/

Is the storm I’m about to bear.

* * * * * * *

(as newlyweds)

She lies in bed while he rides his horse.

Deborah Franklin, wife of Benjamin, dies 250 years ago this week in their home in Philadelphia. Well, technically, it’s theirs. In reality, she has seldom seen him these last years. He has written letters to her, and her to him, but the best that can be said about his husbandly writings is that he’s nice, genial, polite. But that’s it. They have separate worlds, different lives. She has lived for him and he has lived for everyone other than her. And now, the pair is a minus-one. She passes on, 3500 miles away from her husband.

As Deborah Franklin finishes the last hours of a sad marriage and somber life, Paul Revere smacks his horse with a chord. The sting on its backside breaks the animal into a gallop. Man and horse race north up the Post Road from Boston to Portsmouth in the colony of New Hampshire, mud flying from hooves and legs pounding the surface, hands gripping the reins and legs holding a balance. Revere carries written papers and an oral report of armed British naval vessels heading for colonial-rights supporters in Portsmouth. The presumed intent of the vessels and the men aboard them is militaristic, a furthered imperial enforcement of harsh imperial laws—ships will anchor at port, boats will transport Redcoats to shore, units will swarm onto land and into streets. It’s happening. It’s happening. He’ll warn them of the next in happening.

Arrangements for a woman’s burial begin. Arrangements for a man’s return commence.

* * * * * * *

(Clash site)

Over the course of forty-eight hours, spanning December 14 and 15, 250 years ago, hundreds of residents of southeastern New Hampshire flow into Portsmouth in response to alarms and calls of emergency. In each instance, two of the colony’s delegates to the recent Continental Congress in Philadelphia—where Deborah Franklin lay dying—have served as leaders of radical, militant action. On the first day, John Langdon leads a group that removes gunpowder from a British military post, Fort William and Mary. The group also rips down a British national flag. On the second day, John Sullivan leads many of the same people along with newcomers to capture sixteen British cannon and, for the first time, take control of a British national flag in the name of the protestors.

In each instance a handful of British soldiers fight back. On both sides are many wounded and injured but no fatalities.

By today, 250 years ago, a British naval vessel sails into Portsmouth to find a ransacked British military post, bruised and bloody Redcoats, and a town seething with hostility and in, as the colony’s governor states it, “an insurrection.” The silence in Portsmouth masks the biggest and most sustained armed clash to date in the imperial crisis.

The storm is now.

* * * * * * *

(like the sight in Boston harbor)

In the colony of Massachusetts, British imperial governor General Thomas Gage asks his superiors in London for “a sufficient force to command the country, by marching into it, and sending off large detachments to secure obedience through every part of it.” Why? Gage again: “They are trying to usurp the government; nominate officers and resume their old charter, and to raise an army on pay immediately.”

By today, 250 years ago, British Lieutenant John Barker stares out at Boston harbor, the same harbor where a year ago boxes of tea floated in the salt water and where local talk had focused on Native American disguises and war yells.

Barker observes, “The Harbor now cuts a formidable figure, having four Sail of the Line, besides Frigates and Sloops and a great number of Transports.”

Will it be enough for Gage?

* * * * * * *

(awaiting trial)

Tomorrow is his trial. William Ferguson sits in the jail operated by the British Army in Boston.

He is Private William Ferguson, of the 10th Regiment of Foot in the British Army. He is charged with attempted desertion. A jury of nine officers and soldiers will hear the case.

He’s sitting in his cell thinking about the statement he’ll be allowed to make in his own defense. Like many Redcoats in Boston over the past month, Ferguson has been drinking more alcohol each day. It’s loosening his grip on discipline and awareness. Decisions that before were sharp and crisp are now blurred and bleeding. Is he still the soldier he once was?

Everything hangs on his ability to speak persuasively in opposition to the evidence gathered against him.

Ferguson rubs his head and lies back on the thin cot.

The storm crashes in at dawn.

* * * * * * *

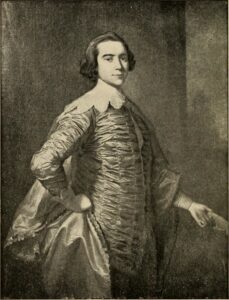

(a depiction two years after the essay)

19-year old Alexander Hamilton publishes his first public essay a few days ago. He’s writing in a New York newspaper in disagreement with “A Westchester Farmer” who had denounced the recent Continental Congress through a printed essay. Hamilton is not entirely sure who is the actual person behind the name “A Westchester Farmer”. It could be his college president, Myles Cooper.

Regardless, Hamilton defends the Continental Congress is his “A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress”. Hamilton asserts that the best approach for colonial-rights supporters is to embrace the Continental Congress and its decisions. Hamilton’s outlook effectively elevates the multi-colonial entity to a position of supreme collective authority in the struggle against the Coercive Acts.

It is this young man’s mindset, a federalist spawned.

* * * * * * *

(Valentine Peers)

In Alexandria, colony of Virginia, 18-year old Valentine Peers, an Irish immigrant, sits in a courtroom, today 250 years ago. He’s in front of the committee organized in Fairfax County to enforce and monitor the “Association”, the name of the policy and apparatus adopted by the Continental Congress; it’s the boycott of British goods to force a change in the British Parliament’s Coercive Acts.

Peers is a partner in a venture that has brought a ship—the Hope—to Alexandria. He purchased linen in Ireland and arranged from shipment of the material to Virginia for re-sale along in communities throughout the Potomac River valley. He acknowledges to the committee that, under the Association, the linen will be seized, sold, and proceeds from the sale will be sent to Boston to support people suffering from the Coercive Acts being implemented by General Thomas Gage.

Painful though it is to sell off his investment in the linens, young Valentine Peers is doing his best to follow the boycott’s procedures as he understands them. He supports colonial rights and pushes his linen investment into the middle of the poker table. Ante up.

But it’s going to be a long winter.

* * * * * * *

(Henry Laurens and a two-year vision)

Henry Laurens is just back to Charleston, colony of South Carolina, from an extended stay in England. He doesn’t know yet the full details of recent development locally in the imperial-colonial crisis. He does know that the current crop of indigo has been jammed up from exportation to England. It’s the result of the boycott and the Association.

Laurens is surprised that so many people in Charleston are openly supportive of colonial rights and opposed to imperial power. He sees “a Spirit and firmness beyond expectation.”

Because of it, Laurens projects “a Set of ragged patriots before the expiration of 1775 and in 1776 we shall begin to deck out Selves in Woolen Cotten Linen and Silk of our own manufacture.”

Interesting that Laurens sees a two-year frame of future-time as important in the current crisis. Give the thing twenty-four months, he believes, and we’ll see a clear turn of events.

* * * * * * *

(a mishap in his first moment of calling)

I’m in the future I wanted, thinks Philip Vickers Fithian. He’s taught school to the children of a plantation owner in Virginia to earn money and have a place to live. All the while, he’s been preparing to serve as a Christian minister and evangelist as his life’s calling.

Yesterday, Fithian delivered his first sermon in front of a congregation. It was at Deerfield, a Native settlement in the colony of Massachusetts. He described it as a “very full assembly.” The first words he heard himself speaking terrified him. He settled down and “preached however, without Notes, and with little difficulty.” The only problem was that someone told him after the church service that he flubbed a prayer—he said he was “desiring of God that the King may become a nursing mother, and the Queen a nursing Father to the Church.”

Aaarrrgghhh! How could I?

Just because it’s your life’s calling doesn’t mean you don’t make mistakes.

* * * * * * *

Also

(Edmund Burke, Parliament member and colonial lobbyist who’s heading to the coffee shop)

Benjamin Franklin, who doesn’t know he’s now a widower with the death of his wife Deborah, writes his first letter to Edmund Burke, a member of the House of Commons sympathetic to the cause of colonial-rights. Franklin invites Burke to come to Waghorn’s Coffeehouse in Westminster tomorrow. Franklin wants to meet with other colonial agents (lobbyists). Burke is also such an agent.

* * * * * * *

(a Jewish prayer for the dying in Prague, soon banned)

Yesterday, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria ejected people of the Jewish faith from Bohemia, Moravia, and Prague. Wielding the power of a monarch, she orders a group of people driven from their homes and communities.

She is the storm.

For You Now

(masses with messes)

Start with a truth. These people aren’t perfect. And forget perfect, sometimes, they aren’t even good, or decent, or acceptable.

For all the warmth, caring, and belonging that Benjamin Franklin displays in his relationships on either side of the Atlantic Ocean, he is relentlessly cold toward Deborah, his wife. For all his patience, insight, and broad-mindedness, he shows little or none of these qualities in his relationship with her. For all his openness to self-improvement and personal growth, he feels zero motivation to strengthen his bond with Deborah.

People are a mess, aren’t they? It’s not just Franklin. All of them in that era, like people in every era, are a jumble of strengths and weaknesses, ups and downs. Yet it’s this human reality of the mess of people when you see great things attempted, great change pursued, great risks run. Frequently, vast events like revolutions are discussed in terms of mass, the masses. I don’t know about anyone else, but I think we should emphasize mess over mass.

Which takes me to the two-day clash at Fort William and Mary in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. What an under-appreciated event. Strikingly so. We need a new chapter in the history of the beginning of the Revolutionary War. Chapter One ought to be Fort William and Mary, not Lexington and Concord. Yes, the latter sequence is a pitched battle and a rural version of urban warfare. Fort William and Mary, however, are the first direct attack on British military property with British forces inside (however small in number). The symbol of British sovereignty, the flag, is desecrated. There is bloodshed. And perhaps most compellingly of all, it is outside Boston and it involves two Continental Congress delegates as overt leaders (not disguised in Native garb) of the assaults.

This inclusion of open armed conflict is an addition of a new realm of the imperial-colonial crisis. Beyond protests and policies, we now see armed, organized, directed violence against a military position with a military goal in mind. The human reality of people-are-a-mess as an ongoing factor has entered the realm of warfare and organized violence, one of the most ferocious avenues of human activity. When war and revolution combine, the mess of people affects the situation every bit as much as the mass of people.

I just want to remind you of what we’re now seeing in Americanism Redux. We have protests. We have some issues that have moved to the forefront while other issues struggle for prominence. We have new entities recommending policies and enforcement mechanisms across the colonies. We have organized armed conflict in more than one colony. Throughout it all, we have an understanding of rights, shifting and imperfect though it may be, a foundation of new public and private liberties.

And next week is Christmas.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: are you like Henry Laurens, who sees the two-year future as a straight-line extension of the present moment?

(your River)