Americanism Redux

August 29, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Are you feeling well? Fever or chills? Aches or soreness?

Tell me a number that describes your pain.

The baby, the child, the adult, each in a different condition and each in the care of someone who cares, or knows, or both. They have a number.

Today, 250 years ago, questions surround the health of the human body and the body politic

* * * * * * *

(Elizabeth grown up)

All of a day, Elizabeth Ann Bayley is all of 24 hours old in the well-kept family home in New York City. Mom and Dad are devout Episcopalians, of the Christian strain that observes elegant rituals and emphasizes reason and intellectualism in their worship. Elizabeth’s parents note the obvious about their baby daughter—she’s unusually small and frail, even for a day-old infant. Her father is a surgeon and he knows that a bad turn of luck with illness might be all it takes to stop this young life. Every cough, every sneeze, every cry of discomfort will ring alarms in the hearts of minds of Dr. Richard and Catherine Bayley.

They won’t know that in the years ahead she’ll cope with sickness and death not of herself but of her sister, mother, father, and husbands. She’ll forsake the family Episcopalian worship style for conversion to Roman Catholicism. And, 201 years into the future, on the eve of the Bicentennial celebration of the United States, Elizabeth will be the first American canonized by the Catholic papacy.

A life in full on a River of miracles.

* * * * * * *

(Liberty’s Mother)

Then there’s little Liberty. Compared to Elizabeth, Liberty Wright is an elder, having been born a full six weeks ago in Pepperell, colony of Massachusetts. Mom is Prudence, Dad is David, and the whole Wright clan is a burning ring-of-fire for American rights. And yes, that’s why they named her Liberty a month-and-a-half ago.

Mom and Dad are out of the house today, 250 years ago, standing in front of the “Publick Meeting House door” with lots of other townsfolks from Pepperell. Out of nothing more and nothing less than a blazing love of the American cause, they’ve found a 100-foot high “Liberty Pole” and today are sticking it into a deep hole in the ground. Not done yet. Next, they made a flag—bright red and deep blue—and up it goes on the Liberty Pole, “with ease.”

At the ceremony, they draft a five-item statement of life as it exists for them in the moment. Item One: civil liberty infringed. Item Two: charter rights taken by Old England’s government. Item Three: English liberties fleeing North America. Item Four: congresses appointed and appointing. Item Five: struggles very high.

The red-and-blue flag sits atop the Liberty Pole, birth pang of a new nation in Pepperell. Prudence Wright returns to baby Liberty, birthed in the home and living in the village.

* * * * * * *

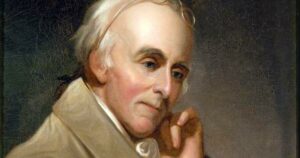

(Rush as an older man, in a consciously chosen pose)

If Prudence wants a doctor’s advice for her new-born baby, she could do a lot worse than Rush.

Dr. Benjamin Rush is a hard-working, studious, and patient-focused medical professional located in Philadelphia. He learned much of his medical knowledge from Dr. William Cullen of Glasgow, Scotland. Cullen’s care of patients favored dietary methods and drinking various natural concoctions to help the body heal itself. Rush added one thing to Cullen’s teachings: physical exercise. He would have emphasized all three to Prudence—proper diet, herb-based teas, and exercise. But he’s too busy and too far away for Prudence.

Today, 250 years ago, Dr. Rush is part of a private, informal, and perhaps even secret meeting six miles from the center of Philadelphia. Dr. Rush and thirteen other people are together in a house, where they’re planning “some information and advice,” according to John Adams, another attendee.

Simply put, the four-person Massachusetts delegation for the “special congress” in Philadelphia is talking with a handful of delegates from Pennsylvania (including Rush), New Hampshire, and South Carolina for a quiet but intense exploration of plans, methods, and strategies for the upcoming congress.

It’s the classic “meeting-before-the-meeting” where agendas and approaches are aired, vetted, and tested. Ever since Adam and Eve in the Garden or Cro-Magnons in the caves, there have always been people huddling in private before the big meeting.

When today’s private session ends in Frankford, Dr. Rush and Adams climb into a carriage and riding toward Philadelphia. Rush notes that Adams asks constant questions, dresses plainly, and seems uninterested in chit-chat.

* * * * * * *

(Ann, a daughter who lived)

Richard Cogdell of North Carolina shares some of the same reality as Rush. He knows someone from Massachusetts and needs a doctor more than he’d ever want to admit. His wife, Lydia Duncan, was born in that New England colony and together they’re coped with the horror of seeing five of their ten children die before adulthood. Through the tragedy, the Cogdell family is a miniature north-south alliance that has held up over time, an outcome that Rush’s meeting at Frankford hoped to emulate.

Today, Cogdell finishes a three-day event in New Bern, colony of North Carolina. He’s been one of 71 representatives at the colony’s first “provincial congress”. They hammered out 28 “Resolves”, including the designation of delegates to travel to Philadelphia for the “special congress”, though they’ll be days or weeks late for any pre-meeting meeting, opening meeting, and subsequent early-on meetings. The Resolves also denounced Parliamentary abuses of colonial rights, supported Boston, agreed with phased-in economic boycotts, and pledged to end the out-of-colony trade in enslaved people, again with phased-in timing. As of this point, the New Bern Resolves reflect a visible consensus among many colonists in many colonies. The now’s version of standard stuff.

A murkier reflection is true for Cogwell’s standing in the cause. Made over the years, he has a long list of offices and positions he’s held responsibly, from sheriff to soldier, lawyer to judge, legislator to local town council member. But—murk alert—he’s on record as having supported the imperial colonial governor in shutting down a local uprising among farmers in the backcountry, to the point of an actual battle, mind you, and he’s skirted the edge between propriety and misconduct in overseeing port inspections, another of his many jobs. And those five surviving children of he and Lydia? Well, he’ll push every single edge as far as he can in the name of their advantage.

Taken together, a slight discomfort appears here, though perhaps no more than a pebble in a shoe.

Not everyone defines good health in the same way.

* * * * * * *

(learn from the people who resisted him)

The printers of the Connecticut Courant newspaper are working on final details of the edition that hits Hartford’s cobblestone streets tomorrow. They’re slotting metal pieces into place, the words of the closing section of a special essay written. The conclusion’s lasting impression will be all the more memorable for the author’s refusal to add his or her name at the end of the Courant’s special essay.

Instead, the author chooses to conclude with one clear connection between the writing and the world in which the reader lives.

The author has written about Dutch uprisings against Spanish rule in the late 16th century, almost two hundred year ago. But it’s only in the conclusion that the author grabs the reader by the collar and shoves the point face-to-face:

“Innumberable were the Hardships of this People, until by their Firmness and Unanimity, under the Conduct of the Prince of Orange, they rose from Oppression, expelled the foreign Troops from their Provinces, and restored their ancient Forms of Government, proving to (Spanish King) Philip by dear Experience, how little the best Conduct and the boldest Armies are able to withstand the torrent of a stubborn and enraged People.”

Is the reader in a condition to rise to that challenge?

* * * * * * *

(Gage, as imagined today)

Thomas Gage is a British military general and not a doctor. Nevertheless, he’s doing the work of diagnosis in a letter he’s writing and sending to the Earl of Dartmouth, his boss in the imperial government in London. As royal governor, Gage is examining the body politic in Massachusetts, taking the public’s temperature and assessing the public’s gaze.

It’s not a pretty report.

Gage asserts to Dartmouth “it is agreed that popular fury was never greater in this Province (Massachusetts) than at present, and it has taken its rise from the old source at Boston, though it has appeared first at a distance (elsewhere in the colony).” The people here “chicane, elude, openly violate, or passively resist the laws as opportunity serves; and opposition to authority is of so long standing, that it has become habitual.”

Habitual.

Gage estimates that the situation is only slightly better in Connecticut and that together—Connecticut and Massachusetts—they amount to the pulse, the blood, and the bone structure of colonial opposition. He recommends that the imperial government focus on these two colonies and that he does “not apprehend any assistance would be given (to them) by the other Colonies.” As far as immediate treatment goes, Gage knows that he might need to march a regiment of soldiers into the interior of Massachusetts if conditions quickly deteriorate.

The general adds a postscript to this letter. Gage observes that unemployment has skyrocketed in Boston because of the port’s forced closure. He states that town leaders are using money donated by other colonies to pay for public welfare assistance—essentially, that’s what it is—by hiring jobless people to labor on repairing boats, cleaning docks, and whatever other make-work tasks can be created for them. Gage wonders if other donors in other colonies would approve of this sort of charity work through their money.

Aren’t they corrupting their own people, Gage asks with a snarl.

* * * * * * *

Health can reach a critical point where the challenge is knowing treatment from cure.

Also

(Cotugno)

On the same day that a future American saint is 24 hours old, the curia of the archdiocese in Rome announces the discovery of a miracle. Nearly two years ago several “Sacred Hosts” of the Catholic Church had been stolen in Rome. The relics and artifacts were found again but in a startling condition—there wasn’t any damage done to then, not a crack, not a scratch, not a smear. An investigation was launched into the explanation for the remarkable outcome.

Today’s conclusion: it was a miracle. Only God could have protected the items.

Part of the process of today’s announcement involved Professor Domenico Cotugno from the University of Naples. He was called in to assist in the investigation. An accomplished scientist credited, among other things, with the discovery of cerebrospinal fluid, Cotugno agreed with the assignment of miraculous to the protection of the stolen articles.

To Cotugno, the anatomical scientist, to say it was unprecedented and inexplicable was not saying enough.

* * * * * * *

(Dartmouth)

The Second Earl of Dartmouth is in London, England today 250 years ago. He has no knowledge of Gage’s letter with his name addressed on it. Indeed, he’ll know of its existence only when his mail arrives from Salem, colony of Massachusetts in four to eight weeks, depending on conditions.

Restated: that’s one to two months, on average, one way.

In this case, it would mean that Dartmouth’s first awareness of Gage’s information and opinions will be between late September and late October. Dartmouth can send his reactions back to Gage, then, at the soonest between early October and early November, arriving in Salem by a few weeks on either side of the year’s end. And that’s not including any other reactions and decisions, besides his own, that Dartmouth would need or want to include. If he needed others’ input and actions, Dartmouth will be lucky to get anything back to Gage before mid-January or February.

All told, call it a minimum of a five-month loop of here/to/there/and/back/again.

That’s roughly a half-year of time when anything can happen that no one predicted or no one forecasted or no one envisioned or no one desired.

It’s today, 250 years ago, and it’s the physical, objective, matter-of-fact environment in which the health of the American body politic exists and unfolds.

For You Now

Today is a day of deep breathing. Some of the content I find for these entries causes me to sit back and take a deep breath. I don’t think that’s simply a result of my nerdness as a history guy and an American-Revolution guy. Runs way beyond that.

We’ll be talking life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness until we’re blue in the face a couple of years from now. I want you to try and remember to recall Redux entries like this one when that time comes.

We’re on the strand of a spider’s web suspended above a dark, black, bottomless chasm.

That’s the nature of time we’re seeing in today’s entry. The ideas and ideals we’ll be commemorating, celebrating, and in some cases criticizing in 2026 must be understood—as best we can, which is dimly—in the context of time I’ve described above. Note what I’ve just written: time, not times, not the time, not any other way except to say t/i/m/e.

Time is every bit as crucial in this story as anything or anyone else. Time is the water and air of it all, nightfall and daylight, matter and anti-matter.

And time is in relationship to space (defined by your shadow) and distance (defined by the length between your shadow and every other shadow chosen at any given moment).

I fear I’m being the pebble in Richard Cogwell’s shoe right now. More irritating than enlightening.

The best I can do is to draw a triangle—one point has Liberty the Pole, one point has Liberty the baby, and one point has Gage’s letter to Dartmouth. And in the center is Pepperell? Boston? Philadelphia? Whatever it is, the whole thing projects from a backdrop of time as known and as an influence that almost defies imagining.

Like the spider web above the chasm.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: how are instant images affecting your sense of reality in the current environment of 2024?

(Your River)