Americanism Redux

August 15, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

You let it in, brought it in, welcomed it in. Doesn’t matter, you chose and that’s fine. Completely okay.

The “it” is the current public political and governmental turmoil around you. You have a stance and a viewpoint and something to say about it.

Part of your life, by choice, opens to the whirlwinds.

* * * * * * *

Don’t do it.

If you go ahead and do it, you’ll be punished by law. By my order.

So declares, this week, James Wright, the colonial-imperial governor of the colony of Georgia. Wright outlaws the gatherings of private people bent upon expressing their grievances against the colonial government and the pronouncement of their intended actions in defense of themselves. Do this kind of meeting and suffer punishment, writes the bewigged governor.

Wright turns to you and your life, saying and asking at the same time: “Go ahead, make my day.”

* * * * * * *

(Peter Tondee, Dirty Harry with a quill pen and paper)

Oh really? That’s your statement? That’s your declaration?

Perfect. We’ll make your day.

So retorts, this week, Peter Tondee, standing at the entrance of his place of business, Tondee’s Tavern, in Savannah, capital of the colony of Georgia.

Tondee held paper and pen as he stood next to his tavern door. One by one, thirty invited men entered Tondee’s for the second organized “provincial” meeting. The men who walked by him were upset, disgruntled, and generally riled up about British reactions to the tea protests. They know they could be next in the loss of liberties and freedoms and they know they are now lawbreakers in the governor’s eyes.

Tondee makes a mark next to the name of each man on his sheet of paper. When he marked all the names as “present”, the outlawed meeting began. It ended a couple of hours later. Attendees voted not to pick delegates for the general congress in Philadelphia. They approved eight Resolves, prefacing each with a Latin adverb, Nenime Contradicente, or “without dissent”. The Resolves included denunciation of British laws against Massachusetts, assertion of colonial rights, and agreement with other colonies to lawfully—yes, lawfully, they want it known—defend those rights.

With parchment paper absorbing the ink of the Resolves, parched throats enjoyed free ale, wine, and punch at Tondee’s after the illegal and semi-secret meeting. Protesting is thirsty work.

Tondee turns to you and your life: “You want on the list?”

* * * * * * *

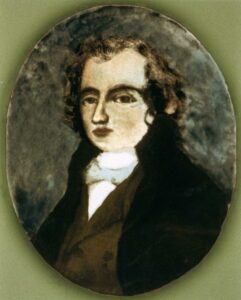

(the fine never paid)

John Penn, today 250 years ago, is as thirsty as any of the thirty men at Tondee’s—but it’s a long way to get a drink, actually, with South Carolina between the tavern and Penn’s new farm near Stovall, colony of North Carolina.

33-years old, John Penn is twelve years a lawyer out of his native Virginia. He’s participating in a Granville County meeting today in North Carolina, one of those Resolves-making gatherings so prevalent in colonies up and down the Atlantic Coast. This one, however, is unique.

Penn has an edge. His attitude toward British-colonial relations has sharpened to the cutting point. His ideas will draw blood if pressed close to the skin.

Not long ago, Penn had spoken out publicly against British King George III. That momentary outburst earned him an arrest and a local judge’s charge of treason and sedition. Friends and sympathizers on a jury watered down the accusation to a penny fine. Penn the knife refused satisfaction to the judge. The penny stayed in his pocket.

Now, today, 250 years ago, Penn slices off a chunk of revenge. The Granville Resolves he endorses states “that these absolute rights we are entitled to as men, by the immutable Laws of Nature, are antecedent to all social and relative duties whatsoever.” If they can’t be protected, if they are threatened and taken away, “a Compact exists that if violated can be rescinded…” It might as well have been seventeenth century philosopher Thomas Hobbes who’d written the words. After all, Hobbes said them first.

Satisfied, Penn rides his horse back to the farm outside Stovall. Hear that? Sounds like something jingling with the trotting horse. Maybe coins in the rider’s pocket.

Penn passes you and asks: “Penny for your thoughts?”

* * * * * * *

(Mercy’s count)

Count them. Five. Five sons. If it all goes bad and the knives come out, five of her sons are at risk.

Mercy Otis Warren of Plymouth, colony of Massachusetts, knows her sons are likely candidates for combat and battle if the current controversy with the British government goes too far and becomes war. Five of Mother Mercy’s boys are within the age range where they’d be expected to pick up a gun and head into the smoking fields and reddened crops.

Mercy adores her family and ancestors’ home in Plymouth. She loves Massachusetts. She cherishes a future where their lives could continue to flourish. She shudders at the thought this life could wither with new British laws and a frightened way of living.

But she aches in imagining her boys “who Buckle on the Harness and perhaps fall a Sacrifice to the Name of Liberty Ere she again revives and spreads her Cheerful Banner over this part of the Globe.”

With moistened eyes, Mercy whispers to you: “What if Woman Liberty needs a war?”

* * * * * * *

(followers of the sheepherder)

“Baaaa”.

“Baaaa.” The sheep bleat to the stout man with the long wooden staff.

He’s Israel Putnam, a veteran officer famed for his irregular fighting during the French and Indian War. Today, 250 years ago, Putnam spends the night with Dr. Joseph Warren in Boston. Warren refers to him as “the celebrated Colonel”. The sheep are Putnam’s donation to the people suffering under harsh British retaliatory laws, and he’s driven them here from his home in Pomfret, colony of Connecticut.

After supping with his sheepherder guest, Warren observes that unless a change occurs, “the people themselves will, in a few years, readily consent to throw off the useless burthens.” Perhaps the day is ahead when Putnam returns with a resource other than livestock. He’s capable of shifting overnight his life from citizen to soldier, from British colonist to American patriot, from farmer of sheep to commander of sons.

Warren asks of you: “Which do you need, the wool or the meat?”

* * * * * * *

(mark of the unknown writer)

“Z” has something to tell you about listening to the right person.

“Z” is the chosen pen name of an essayist whose article is in newspapers in northern New Jersey and southern New York. He writes that public funds at the heart of the imperial-colonial clash can be split into separate but equal categories. It’s an argument trotted out before—about six or seven years ago—whereby imperial power is used for duties on foreign trade and overseas commerce while colonial power concentrates on domestic taxes. That’s a potential compromise: the mother country has tariff-power and the colonies have tax-power. Z brings the tax/tariff split back as the basis for a resolution to the current situation; indeed, Z is interested in resolving problems much more than proclaiming resolves. Z urges readers to be steady in responsibilities and guarded in liberties.

Z warns that “we may in the heat and hurry of our spirits inflamed by men who perhaps are without consequence but in times of tumult and disorder, be involved in the horrors of a civil war, and to the ruin of our liberty be compelled to submit by force.” In other words, some nasty men will be leaders only in bad times. They’ll carry us into hell if we’re unaware. And hell is where we’ll be if we have to fight.

Z is curious: “Do you want to save the sheep from slaughter?”

* * * * * * *

(Smithfield today)

Has it come to this? My seven children, my beautiful house, my new long-awaited home.

Crack, the axe hits the tree. Crash, the tree hits the ground. Thud and thunk and plop, the stripped trunk is lugged on top of the logs already stacked and laid end-to-end as the walls of a fort.

Susanna Smith Preston watches today, 250 years ago, as her husband and a small group of men begin chopping down trees and hauling them into place around her plank-board house called “Smithfield” in honor of her family (near the campus of modern-day Virginia Tech University).

The log-stacks will go up seven, eight, maybe ten feet high. The fort around Smithfield is taking shape.

It’s an awful sign of war along the upper Ohio River valley in western Virginia and western Pennsylvania, between Native warriors from the Shawnee and Cherokee tribes and settlers like the Prestons at Smithfield and various units of volunteer colonial soldiers coming from elsewhere in Virginia.

Susanna is shaken, on the verge of tears. From the windows of Smithfield, beyond the meadows, out in the hardwood forest, she sees a darkness in the green.

Further into the green and deeper into the forest, Mingo warriors led by Logan sit at campfires, tightening bow strings and sharpening arrowheads. They wanted to avenge the murder of Logan’s family and the seizure of Mingo land. Logan had cried when his family was killed.

“Which will dry the tears,” a body-less voice asks you, “the leather shirt from the wigwam or the flannel dress from the house?

* * * * * * *

(stoned Lewis)

Colonel Andrew Lewis and three other colonial officers of Virginia have met this week at Lewis’s home (near modern-day Lewisburg, Virginia). Lewis learned that Governor Dunmore, governor of the colony of Virginia, is arming and organizing men near Williamsburg. Dunmore plans to lead them himself into the Ohio valley for a strike against Natives resisting colonial settlements in the region. At the meeting Lewis and his three comrades decide to begin their own assembly of temporary soldiers. They also choose where to march in anticipation of joining with Dunmore’s movement.

A colonial officer and an imperial governor are at odds in nearly every other part of the Atlantic seaboard. Not here, and not these two. They are aligned and preparing for war alongside each other. Facing west, with land to fight over, a place to conquer, a future to imagine on the O-ee-o and Ohio.

Colonel Lewis invites you to enlist: “Will you serve for King and Country?”

* * * * * * *

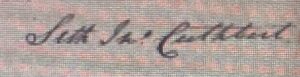

(his signature)

Seth Cuthbert worries about his mother. He’s in what he calls “Indian land” near Horse Creek, colony of Georgia. It’s hard to move her and the rest of the Cuthbert family toward Horse Creek. She expects to carry a lot of the family furniture with them, making travel by wagon or boat nearly impossible. Dealing with her adds to a future difficult to plan.

Seth can’t stop thinking about so many other things for the move—whether indigo will grow, whether people will be found for labor, whether he should try to be a broker for someone else, whether he be a wholesaler to other retailers. Whether, whether, whether.

No one else cares. All they want to talk about, according to Seth, is “Boston, Resolutions, and an Indian War.” Seth expects the latter of the trio will dominate; he sees war breaking out between the colony of Georgia and Native Creek tribes. Others agree—and that’s why the thirty men at Tondee’s tavern voted not to send delegates to Philadelphia. The colony’s focus should be on the Creeks.

Seth would like to know from you: “What do I tell my mother?”

* * * * * * *

(will-writer)

Peyton’s focus is his wife and children.

Before leaving as a Virginia delegate for the congress in Philadelphia, Peyton Randolph finalizes his will.

The biggest complication that he’s sorted through in the will is the people he has enslaved. Adults and children, male and female, they will be dispersed as Randolph decides. They embody a source of labor, the coverage of debt, the obligation of relationship. It’s a power any ruler would be jealous of and every tyrant would understand.

Randolph was the man marching at the head of the Assembly’s public parade back at the end of May, a shocking public protest of the governor’s dismissal of the legislature for its reaction to British policy against Boston. And now, before leaving for the special multi-colonial congress, Randolph chooses to get his earthly afterlife in order.

Hmmm. “Interesting timing, don’t you think?”

* * * * * * *

You open a door to your house. Air rushes in, fresh and alive. The stale is gone and so is the dust. Closing your eyes, taking deep breaths, the feeling is wonderful, yourself restored. You step outside and see the breeze has become a wind.

Reaching for the door, someone asks you: should it be closed, secured, or left as is?

Also

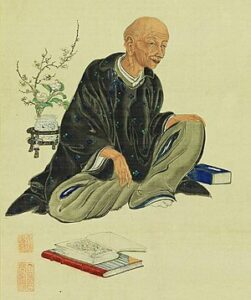

(Sugita Genpaku)

He’s done. Finished. After more than three years, after eleven different hand-written manuscripts, Sugita Genpaku of Edo (Tokyo) has completed his work, a bridge of new knowledge from central Europe to eastern Asia.

It’s known as “Kaitai Shinsho”, and it’s the first fully translated writing of a Dutch textbook on human anatomy, now available to scholars and specialists in the kindgom of Japan.

Genpaku taught himself the German language. He’d read the German edition of Johann Kulmus’s 1734 book on anatomy. He had followed the book’s material and, with other Japanese scholars, conducted dissections to verify the processes outlined in the book. Genpaku concluded that the traditional methods taught by Chinese tutors were flawed. He saw the Dutch approach to anatomy was correct and should be shared with doctors across the Japanese kingdom. His completed translation is the first step toward that new reality.

For You Now

So much swirling around us, it feels. There’s a part of your life where you’ve decided the new air is needed. And from the public conditions out there, you’ve let it in.

We’re seeing varying sides of the same story today from 250 years ago. They have let the air in as well. They’re determining how best to manage the flow. Not everything is perfect or even preferred, far from it, though some of it has a goodness potential in the minds of selected people.

I think the point best made here is that the opening you’ve offered is the opening the air enters. But let’s not mistake the choices for the completions. The opening is the path of direction, not the source of elements flying in. The opening is the encounter’s first part, not the experience’s full state. The opening is a beginning you see and not the end you’ll ultimately absorb.

By all means, enjoy the air. By all means, embrace the air. By all means, engage the thought and feel of air stirring the surface of waters you see ahead.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: in the spirit of Genpaku, where do we most need new knowledge?

(Your River)