Americanism Redux

May 23, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Displaced.

(an example of calmer displacement)

Displacement is what happens when a new thing shoves aside existing things. They either slide down your list of priorities, become something different through interaction with the new thing that does the displacing, or simply disappear entirely.

The first feeling of discomfort occurs in displacement.

* * * * * * *

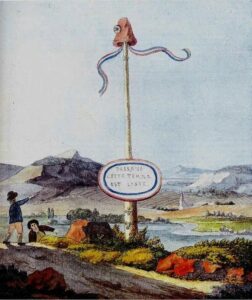

(a Liberty Pole as drawn by Goethe)

Welcome to Farmington, colony of Connecticut.

See the wooden pole in the center of town? Guess it’s height. Sorry, I’ll just tell you—45 feet, to the inch. We’ve done it in honor of John Wilkes, the Parliament member and Scottish writer of his “Essay Number 45” back in the early ’60s that championed liberty and civic freedom. A 45-foot tall pole is our essay, showing our love of liberty and freedom, too, both of which we exercised this week, a few days ago, when 1000 of us burned a copy of the Boston Port Act. Those flames ate it up. We then shouted our approval for five resolutions on behalf of Boston—that we’re in this together; that the devil has the British Parliament in his grip; that the Port Act is an illegal insult; that “pimps and parasites” are now in charge of the imperial government; and that “we scorn the chains of slavery…and till time shall be no more, that god-like virtue will blazon our hemisphere.”

Whatever else we were worrying about last week, last month, last year, forget it now. We’re standing in awe of the 45-foot Liberty Pole, standing alongside our Boston brethren, standing up to the dark forces in London bent upon destroying who we are. As of today, this is all that matters.

* * * * * * *

(City Tavern)

It’s a long way from Farmington to Philadelphia. Several days, in fact. Even further in other ways, which you’ll soon see.

It’s only a couple of days after the Farmington event when a related yet quite different event occurs in Philadelphia, colony of Pennsylvania. In the midst of the ongoing dispute over a Connecticut group’s effort to take control of a settlement in Pennsylvania, action unfolded in Philadelphia against the Boston Port Act. In popular City Tavern “a great Number of respectable Inhabitants” held an evening meeting to decide on a response to the new law.

A participant sat amid City Tavern’s soft light of burning wicks and burning logs and despaired about trying to guess what a collected body of people think and believe together in such a moment. Still, among the wine glasses and ale tankards, a general agreement could be felt and seen and heard. After grave nods of heads in support of Boston, heads kept nodding at the recommendation to craft a firm, respectful statement of grievances meant for sending to King George III, and that the best way to do that was to convene a general congress with representatives from all the colonies to hash out the wording. Head shook at the Boston Circular’s idea of banning the importation of British goods and the exportation of American goods to the British market seemed a step too far. Best left as a last resort. More nodding.

Glasses emptied. Chairs pushed toward the tables. The glow fades to dark.

No Liberty Pole. No paper in flames. No snarling about pimps and devils. Yes, Philadelphia is a long way from Farmington.

Good night, all.

* * * * * * *

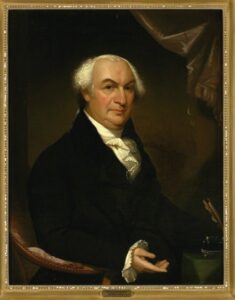

(Gouverneur Morris)

In between is New York City and another meeting of the new group called “the Committee of Fifty-One.”

The miles-wide range of opinion that showed itself in the first meeting is even more evident in the dialogue of May 20, a day ahead of Philadelphia and a day behind Farmington. Gouverneur Morris writes about the Committee of Fifty-One’s meeting.

To Morris “some daring coxcombs” have been driving hard to overturn British imperial rule for the past ten years. “Coxcomb” says it all: it means fool, jester, jokester. These people are a “mob” to Morris, and as mobs will do, he predicts a veering out of control and a careening toward the destruction of all order and decency in daily life. He blasts them for having the self-delusion to start actual debates about which form of government is best, democratic or aristocratic. Morris despises them and their talk. He’s thankful that a group of “patricians” have joined the Fifty-One. They’re the only thing preventing our being “under the domination of a riotous mob.” Sooner or later, he fears, the joke’s on us and not on them. Chaos kills.

As Morris jabs and stabs at the mob with his quill pen, one of those patrician-members of the Fifty-One, 29-year old John Jay (and future member of the three-writer team responsible for The Federalist Papers) uses a softer stroke to write his views of the meeting. Jay acknowledges “the common cause”. He also groans from attempting to offer clear analysis and make good decisions as events plunge ahead and time races forward. He wants to think.

Can the burden Jay carries contain the mob Morris fears?

* * * * * * *

(upper floor)

Today, 250 years ago, second floor of the capitol building in Williamsburg, colony of Virginia, a small group of men shake hands and signal approval. With Thomas Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee, and Patrick Henry among them, they agree to call for a “day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer”. In a couple of days they’ll introduce the call as a resolution to the colony’s legislature. There’s cleverness here—the resolution will raise the issue of the Boston Port Act among the colony’s legislators but not take a public stand of opposition and denunciation or, and this is an important “or”, require further choice of action.

Put a focus on it, give people time and space to think about it, and find a path forward to do something about it.

From Farmington River in Connecticut to the James River in Virginia, waters flow their own way.

* * * * * * *

(one of the community meetings)

And on it rolls, the crisis over what to do about Boston and the Port Act nailed on Parliament’s door. Over the past week, standing at 250 years ago today, a separate emergency community meeting has been called in each of the following colonies: Maryland, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina. Two separate community meetings have been held in both New York and Connecticut. Three such meetings have occurred in Rhode Island, a half-dozen in New Hampshire, and more than twice that number in Massachusetts. The newspaper Boston Evening Post prints several of the meetings’ statements.

This newspaper also features an historical description of colonial contributions to the expansion of the British Empire. Forget not—the Empire and its colonies have grown together.

* * * * * * *

(seeking freedom’s air in Chester County)

Ruth McGee sees growth in freedom, and she’s expecting a new gown, petticoat, and apron as part of her freedom.

These items, along with a pocket full of money and eight months of education, were supposed to mean self-sufficiency for her and her child. Her “Master”, so-called, Josiah Hibbard had promised to furnish all this at the end of her seven-year servitude with him. She does works for him over that period and he gives her the “freedom dues” at the end of that period. Except he hasn’t and he refuses. Worse yet, he had her jailed for a time. Now she’s out, denied what’s owed her, and unable to earn any sort of living to keep her child and herself going. Today, 250 years ago, Ruth convinces a sympathetic friend to write and file a “petition” on her behalf to the Chester County (colony of Pennsylvania) judges to use in seeking satisfaction from Hibbard.

The semi-parallels reveal themselves—Ruth’s petition as the colonists’ proposed petition, Hibbard’s stance as Parliament’s stance, and the Chester County officials as….well…what exactly? King George III?

Dependence, independence, and the rough ground between.

* * * * * * *

(seeking freedom’s air in Virginia)

The people listed in this week’s edition of the Virginia Gazette understand the plight of Ruth McGee and her journey from dependence to independence. There’s so many of them to account for that the printer has produced a special “Postscript” edition to list and describe them.

Thomas Smith is selling a boatload of Ruth McGee-like “indented servants” fresh from London, England. Must be almost a hundred to choose from. Bring cash, credit, or tobacco for exchange and you can get almost any skilled tradesman or tradeswoman imaginable, ranging from book-keepers to bricklayers. Pay him, sign here, and take them.

Bob and Bristol are enslaved men escaped from Surrey County. Bob is intelligent, confident, capable, and a spellbinding talker. Bristol will do whatever Bob tells him to do.

George, Joe, and Archer have similarly escaped as enslaved men, though from Warwick County. All three are affable, athletic, and friendly. They won’t hesitate to pass the time in good conversation.

Thomas Puttrell and Edward Duberg are indentured servants who have escaped from their contracted owners in Westmoreland County. They have experience at sea, have traveled extensively back and forth to Europe, and know a variety of skills and trades.

Betty is also on the run, an escaped enslaved woman from the James River valley. She knows how to help tend and maintain a tavern.

And Joseph Davenport, Hezekiah Ford, and James Brown have each announced their intent to leave the colony of Virginia in the coming weeks. They’ll depart, not escape, at the time of their choosing, unconcerned with people offering money for their capture and return.

Dependence.

The

Independence.

rough

Denial of freedom.

ground

Enjoyment of freedom.

between.

* * * * * * *

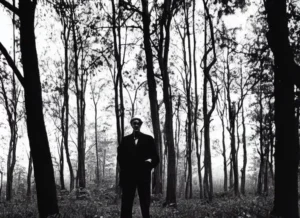

(modern position of Ryegate)

Today, 250 years ago, in Ryegate, colony of New Hampshire (in disputed ground), James Whitelaw and David Allan can’t decide what they’re happier for.

Is it the four acres of ground they’ve cleared with axe, pick, shovel, scythe, and plow?

Or is it the ten people from their Scottish homeland who’ve just arrived on horseback and in horse-drawn wagons, people who will now be their neighbors in this newly drawn town? Whitelaw and Allan welcome them with hearty handshakes, hugs, and slaps on the backs.

The scent of pine floats on a warm spring wind. Deer are seen less in these woods, though geese fly overhead. Soon, the black flies will be out. This band of Scots know that life was, is, and will be hard. They only want a chance to make it what they can.

* * * * * * *

It’s a day of displacing.

Also

(Church of Scotland)

Today, 250 years ago, half a world from Ryegate, the elders and ministers of the Church of Scotland send their happiest best wishes to King George III on the birth of his son: “The loyalty which we bear to our Sovereign, and a deep sense of the intimate connection betwixt the prospects of your royal family and the public welfare, increase our satisfaction.”

* * * * * * *

(George III will approve)

George III will read their declaration later today, or soon enough when he can spare the time. At the moment he has other duties to attend to—namely, giving his formal approval to two new laws of Parliament designed and enacted as part of the punishment/reform/reaction to the Boston tea protests. Added to the Port Act, they now make a trio of new laws that address the anti-tea situation in Massachusetts.

The new Massachusetts Government Act wipes out the colony’s special charter and replaces the elected upper council with a king-appointed council, expands the powers of the new military governor, General Thomas Gage, and allows town meetings to occur only with the governor’s approval. The purpose, as Lord North said, is “to take the executive power from the hands of the democratic part of government.”

The new Administration of Justice Act further gives Gage the power to shift the trial of any British imperial official accused of wrong-doing from a location in Massachusetts to a location in England or another colony. The goal, it’s said, is to ensure a fair trial.

* * * * * * *

(Francisco Garces)

Francisco Garces, the Franciscan friar, has asked two friars at the Cocomaricopa rancheria in the valleys of the Gila and Colorado Rivers, to copy out the last half of his diary. Here, there is no other way to make duplicates. Garces will use his freed-up time to write a letter to the Halchidhamas Natives. He hopes his words will convince them to continue keeping the peace with a half-dozen neighboring tribes. With such a peace, or at least the absence of formal war, Garces believes his chances at finding his own route to Monterey will be better. He’d prefer such a route to any claimed by the Spanish military officer Juan Bautista de Anza. Relations between the Catholic leadership and imperial politico-military personnel are often uneasy here in northern New Spain, and Native tribes look for every opportunity to exploit the tensions in their resistance to Spanish control.

* * * * * * *

(Rohilla warrior)

Natives in another region of the British Empire, the Rohilla, are on the move after a severe defeat by Awadh warriors in battle. The Rohilla are descendants of the Afghani Pashtun tribe who’ve entered the region (modern India) on a quest for control. The British East India Company views the Rohilla as threats to order and stability and, supported by British Governor-General Warren Hastings, funded Awadh involvement against the Rohilla. Having had their leader killed in battle a month ago, the remaining Rohilla have decided to withdraw into the northern plains of India to continue their struggle. It’s conceivable that members of the British military may be relocated here to crush the Rohilla.

The British East India Company. A British Governor-General. A series of clashes with aggressive Natives.

A sound of rhyme from an edge of empire.

For You Now

(but what if you can’t measure the cube?)

The Port Act is a reaction to Boston’s tea protests. It is also new action in Major Change. In landing on the ground, it displaces other things. The displacement spreads as knowledge of the action spreads. Everything and everyone in each new place of knowing will be touched and affected, one way or another. These effects will be counter-reactions as formed by thoughts, talks, speeches, writings, and more.

The River rounds a bend and new tributaries flow in with flooded waters. The bottom goes from clear to unseen and ripples become rapids.

The abundance of community meetings show unity of sympathy. From there, unity falls away, consensus drifts away. Phrasing like “the common cause” is heard frequently but without an abundance of common actions…with one exception. Everyone has reasons for agreeing to hold a formal meeting in a separate place attended by chosen people. That’s the exception, but is it exceptional? People will have the final say.

And then you have lives living life. Here again, the thread is people. Go back and re-read the stories in the Chester County petition and the Virginia newspaper’s postscript edition. They’re written as the River hits the bend. Down-river is where their writing will be read.

Hear the sound of water coming from where the future displaces the past.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: have we entered a Bend of “our common cause”? Are you, perhaps, already there?

(River displacing)