Americanism Redux

May 16, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

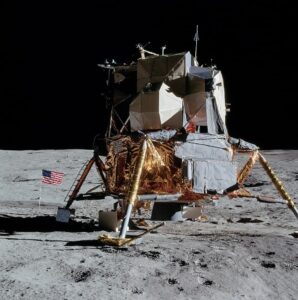

(it has landed)

No more drift, or glide, or float, or motion in air. No more.

Instead, on solid ground, the law has landed.

* * * * * * *

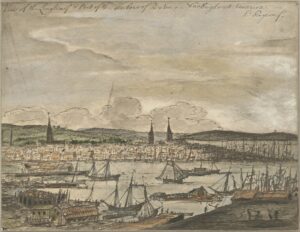

(where it landed)

Slightly less than a week ago, Boston’s residents read or heard read words of the Boston Port Act passed by Parliament and approved by King George III. The Act, fundamentally, says this: the community of Boston has three weeks (until June 1) to pay for the East India Company tea destroyed five months ago. If no payment is forthcoming, British imperial officials, backed by the power of the British Royal Navy, will close, shut, and seal up the port.

“May God most gracious behold our state!”, writes a Christian minister who lives near Boston.

This is “most ignominious, cruel, and unjust,” writes the Boston Committee of Correspondence in a “Circular” mailed out to the colony’s towns and villages, and to other British colonies. The Circular’s writer decries that no chance was given to present the colonists’ views, no opportunity offered to refute claims and charges. Information at hand suggests that other laws of punishment will also be passed.

“The single question then,” the Circular asserts, “is whether you consider Boston as now suffering in the common cause.”

The Circular’s writers, Samuel Adams among them, conclude: your liberties are as much in danger as ours are. So will you, fellow Colonies and Colonists, join us again in a suspension of trade with Great Britain until this new and horrific Act is repealed, like we’ve done before in the prior decade?

* * * * * * *

(the object of the show)

Today, 250 years ago, town officials in Boston prepare for the arrival of British General Thomas Gage, successor to the prior governor, the embattled Thomas Hutchison. Redcoated Gage will oversee enforcement of the Boston Port Act after June 1, along with any other new law enacted. The plans for Gage’s reception involve an array of British soldiers, some on foot and some mounted on horseback, escorts for Gage’s entry into the community. The plans also consist of a series of greetings and meetings.

In their own way, the reception plans are a colonial town’s version of the imperial government’s Port Act. They provide a degree of formality, a dose of officialdom, a dance choreographed between power owned and power sought.

Gage prepares, too. He’s ready to dance. Passenger on a ship from New York City that lands in Boston tomorrow, the redcoated general writes his speech and plans his conduct. His remarks and movements will be the imperial response to whatever gestures and symbols the colonists will have for him upon arrival and upon entry. He’s polishing words and thoughts as carefully as servants have done with his high black leather boots, his brass sword, his metal buttons on the scarlet red military coat.

Even distrust can have a ceremony.

* * * * * * *

(Fraunces Tavern)

The eyes of Isaac and Margarita meet, husband looking at wife, her touch and nod of her head showing that she knows the day will be long for him. Sighing, he’s out the door, today 250 years ago. Isaac Low is off to Fraunces Tavern on Pearl Street in New York City. He’ll be the chosen leader of an intriguingly named group—”the General Committee of the Fifty-One.” The number is the list of participants, including Low. The name harkens up British Parliament member and Scotsman John Wilkes, regarded as a staunch friend of public and private liberty, a hater of abusive kingly power, and associated in 1763 with “the Forty-Five” of his own infamous anti-king essay—the 45th in a series he’d written—and henceforth a code and tagline for groups committed to more freedom and less authority.

Isaac Low and the General Committee of the Fifty-One know the Circular and the Boston Port Act, and they are the first major assembly of people devoted to responding to their respective contents. New York is fast.

Low will be standing or seated at the front of the Fifty-One in a few hours from now. Some of the people in the tavern will be those who compared themselves to Mohawk Native warriors and urged tea protestors to dress in warrior garb. With them, Low will start the churn of finding consensus on what to do, why to do it, and when to do it as well as the not-what, the not-why, and the not-when, a task equally difficult. Group meetings about divisive topics can be hellish scenes.

Low’s been here before, a kind of living embodiment of what Boston’s Circular expressed. He had opposed the Stamp Act of 1765, supported collective colonial action in response, and endorsed the resolutions that eased tensions that near-decade ago. He’s also far more a Britisher at heart than a Wilkesian Forty-Fiver in nature, and in family immediate and extended he’s a believer in king, the king’s country, and all things feeding into the existence of kings. The troubles between empire and colonies are, to Mrs and Mr Low, obstacles to be removed in the name of continuity and continuance of a two-sided Britain connected by an ocean.

Low will lean hard on the better times of these past ten years for an updated resolution to today’s problems. And who knows—in those recent memories he may find the key to a happy toast at the tavern and a thankful smile at home.

* * * * * * *

(The Massachusetts of Maynard)

Stephen Maynard stands in front of a group, too. He’s wearing a smile of gratitude and satisfaction. Almost everyone in today’s town meeting of Westborough, colony of Massachusetts, has voted “yes” or “aye” at the call of his name. They’ve chosen him, “nearly unanimously” as a bystander judged it, to be the town’s “representative” in the hour-by-hour mounting fury over the Boston Port Act. Townsfolk of Westborough will rely on him as their shared mind and defined conscience for whatever else erupts in the foreseeable days and weeks ahead.

Maynard lives in a sort of permanent town meeting in his own home. He’s a father of ten children in a blended family—children from his deceased wife and children from his second and current wife—together with an enslaved family of father, mother, and child. In age, gender, race, roles, and more, his household is a Massachusetts in miniature.

Whenever the demand comes to meet with other elected representatives, Maynard knows how he sees the issue. It’s colonial rights first and most, imperial power last and least. He knows colonists opposed to imperial power had succeeded before and believes they can do so again.

* * * * * * *

(ends of the spectrum)

Two settlements, two places, two outlooks on improvement.

In crisply arranged Alexandria, colony of Virginia, a quartet of men have formed to help the small town improve. Robert Adam, John Carlyle, John Dalton, and William Ramsay have thought about it and have come to the conclusion that four steps are critical for their town’s future: one, decrease the tax on rum; two, increase the size of the town’s acreage; three, bring order and standards to the herring trade; and four, toughen the rules for hogs, geese, and goats caught running loose. Give us the ability to do these four things, they say to Virginia’s legislature, and watch us grow.

In vaguely named “Illinois Country”, a three-man committee speaking on behalf of investors and settlers seek improvement for an entire region between the Mississippi and Wabash Rivers. David Franks, William Murray, and John Campbell of Philadelphia, colony of Pennsylvania, are requesting acknowledgement from the Lord Chancellor of London and Earl of Dunmore, Governor of Virginia, of their lawful purchase and initial settlement—a handful of people, actually—in the prairie lands of “Illinois”. They emphasize that their work will “civilize” Natives living there while at the same time providing a strategic buffer between hostile Natives and more established British colonial settlements in the Ohio country. The trio adds that their project is within the “limits” but not the “jurisdiction” of Dunmore’s Virginia. Recognize us as having the ability to provide these things, they say to imperial officials higher up the hierarchical chain, and watch us flourish.

Ends of the spectrum they are indeed, a coastal town and a prairie region, on a day being lived by Thomas Gage, Isaac Low, and Stephen Maynard.

* * * * * * *

(her grave)

At night he hears her voice. His beloved Anna, dead for a year, torn from his life by God, torn in the way that a whip tears into skin when the enslaved are punished. Anna lost her life because her husband, Moses, had sinned. God saw the sin of Moses’s enslavement of black men, women, and children and God judged that Moses would never see his wife alive again. That’s how Moses sees it when he hears her voice.

Moses Brown of Providence, colony of Rhode Island, freed his enslaved people as penance for his wife’s death. Moses Brown surrendered his spiritual faith as a Baptist and took on the spiritual beliefs of Quakers, the sect committed to stopping enslavement. Moses Brown, today 250 years ago, is again meeting with members of Rhode Island’s Assembly, the legislature, to sew and stitch together a coalition that will vote in favor of a ban on the overseas slave trade that profits his brother John and, before, profited Moses.

Moses prepares for his next meeting knowing he may need to alter his bill’s language here, massage a passage there, soften a point anywhere, in order to gain the necessary votes.

Maybe, soon, he’ll have something to say to the voice, the sound that changed his life.

* * * * * * *

Yes, the law has landed and new sounds have started.

Also

(their logo today)

A second-generation business owner writes a letter in England. He is Thomas Longman, 44 years old, current owner and proud owner of Longman Booksellers, located in London. Longman worries about the Boston Port Act and its likely impact on his friends in Boston and the bookselling business network he has there. His letter is to a young man almost half his age and twice his weight—Henry Knox, a bookbuyer-bookseller in Boston, 24 years old and 250 pounds heavy. Knox is smart, quick-thinking, and a lover of reading. Knox operates a successful business transmitting Longman’s selections to the Boston reading marketplace. But Knox is increasingly as much customer as retailer—he’s becoming obsessed with reading the latest military how-to manuals and publications (nine years into the future, Knox will play a crucial role in assisting George Washington’s defeat of a military coup). Regardless, Longman fears for his friend’s well-being in light of the newly enacted Boston Port Act.

To some colonists who despise the new Act, Longman is the human face of an England-based business community that can help pressure imperial lawmakers into reversing course and repealing the law. Could history, after all, repeat itself?

* * * * * * *

(Louis XVI)

In the royal palace of Versailles, France a 29 year-old man wears a new piece of headgear, a crown. He is Louis XVI, grandson of the now-dead Louis XV, a fatality of smallpox. Louis XVI is intelligent, curious, and a hard worker when he sets his mind to it. He’s not as mature as his 29 years would suggest, easily given to semi-tantrums and a stifling self-doubt. He’s stuck in a five-year old marriage to Marie-Antoinette where he struggles to perform sexually and is considering drastic surgical measures to change the situation.

His position as ruler meant that no one had chosen him. His birth was his only claim to govern, his only footing in power. Beneath him—and literally, it meant below—the new king sat atop a French society stuffed into three categories or estates, the clergy, nobility, and a sprawling middle/working/peasant human terrain. Starvation was often the plight of people outside the nobility and clergy. For the privileged and the elite of this world, life was grand and sheltered. For everyone else, life was hard and rough.

Louis XVI would soon begin considering his next step. A recent trend of government reform that sought to reduce power in the provinces and tighten Paris’s control might be a good first-choice. Perhaps unwind that reform, loosen up central restraints, and edge toward some distant horizon of national improvement.

Today’s a good day to start.

For You Now

(Port of the Circular)

The river won’t wait. The river is alive and moving wherever you choose to enter.

I keep thinking about the single question posed in the Boston Circular. Will the rest of you join up? Aren’t we in this together? Can’t you see what’s coming?

Well, fair enough, three questions springing from one.

What does joining require? Moses Brown ought to be regarded here. His life exploded in his love’s death. In the exploding he underwent a change that he wants to spread to others after himself. He aims a single spear to stop a single aspect (international slave-trading) into the massive beast (enslavement in forced labor). His struggle isn’t uphill, it’s upmountain. Fighting as he goes, his ascent is the ability to gain agreement, one person and step at a time. He’s climbing as Quaker, by the Book of God. If he’s lucky, his brother will join him in scaling the rockface. Really lucky.

The myself of Brown’s nightmares are not the ourselves of the Boston Committee of Correspondence’s writing. It’s a high enough mountain by yourself but it’s a dozen Everests when you want a group, community, or nation to climb it with you. Can everyone cling to the same rope?

The Circular’s single question also invokes the re-tracing of flat ground. It states outright that reversion to prior protests and collective action is a good decision. People can find steadiness—comfort—in second use of a proven method. Nevertheless, the acceptance of that method inevitably requires expansion into other places and people outside Boston and Massachusetts. Have two or five or nine years changed anything elsewhere? Will the cause travel the same now in every mile that it did then?

If we see anything we see this thing—that agreement on opposition is not the same as consensus on solution. And if more laws like the Boston Port Act are also coming, the chances grow of pieces and fragments splintering and crashing down from above.

The law has landed and a river cuts through the rock of the canyon.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: which seems more cohesive and resilient to you now in a public and civic sense, the opposition to something or the solution to something. Will it withstand an additional change?

(Your River)