Americanism Redux

January 16, Your Today, 250 Years Ago, In 1775

Let’s allow an illusion. You’ve got your minutes and hours and days down to your own control, that everything you’re doing flows into a narrowly formed funnel over and over again. It’s fine to think it. Go ahead and live it.

Just know that up-top, where time runs, life doesn’t care.

It’s always everywhere, moving in and through and around any narrowing you think you’ve done.

* * * * * * *

One last time, today, 250 years ago, he picks up a worn leather cloth. He rubs it over the surface, giving a shine to the amber color and taking off the last flecks of dust off the surface. There, that ought to do it. He sits on his wooden bench and admires his finished product.

Work became craft and craft became art.

Today, Eber Stone lives in Guilford, colony of Connecticut. In one hand he’s holding a gleaming new powderhorn. Some days ago he began scraping off the exterior layers, from the back of the horn to the tip. Then, fastening the smoothed-out horn into a position where he could apply pressure and maintain precision, he began his markings, etchings, and carvings. He went a quarter-inch or half-inch at a time, always knowing the next curve or loop he wants to fashion.

Letters, words, numbers, lines. He topped it off his scrimshaw with his own statement of where his life is at this moment, today, 250 years ago.

“My day’s to come if God will lend/

My King and Country I’ll defend”

Eber’s next step is to measure the chord he’ll tie to the horn to ensure a natural fit around his right side, waist-high.

Finally, he’ll pour in the gunpowder and hang the horn on a peg in the wall.

* * * * * * *

Thomas Johnson flips through the last few pages of a small book. He’s in a chair, warmed by a fire in his home, in Annapolis, colony of Maryland, today, 250 years ago.

Interesting, he thinks. Clever, he thinks. I should try this, he thinks.

He’s reading instructions on the use of hemp in making rough fabric for cloth. Johnson knows how to use flax for the process. It’s the standard material. But he’s never experimented with hemp. Hmmm. Might be worth doing.

Everything is up for re-thinking because of the current imperial-colonial crisis over the British retaliatory Coercive Acts against Massachusetts and Boston and the colonies’ counter-retaliation of an economic boycott.

From his chair, Thomas Johnson senses new problems creating new opportunities through new techniques. He closes the book. Hmmm. Hemp here, cloth there.

He’s deciding to share the idea with someone he knows is always open to the business of newness.

* * * * * * *

George Washington doesn’t know it yet but he’ll receive a brief letter very soon from Thomas Johnson. It will be a blend of book report and business proposal regarding hemp.

What George Washington does know, today, 250 years ago, is that he’s having to endure one of life’s worst moments:

the disappointment of a dying friend.

Colonel John West IV knows that his own death is not far off. The doctors tell him that and, more meaningfully, he feels that himself. Sure, he’ll hope for the best. But deep down, he knows it won’t matter. It’s time to think about settling accounts.

For West, that means trying to provide for his only son. That’s why he wrote to Washington and asked him to take over the parenting of Roger. He wants Washington to raise him as a kind of foster-son.

An agonizing Washington writes today that he just can’t do it. He can’t see how to make it work. He admires and respects West; he recognizes the almost unmeasurable trust that West is placing in him in making the request. But, gulp, no, it can’t happen. So deeply sorry.

Washington imagines the pain on West’s face as he reads the letter of decision.

* * * * * * *

(Arnold home)

In New Haven, the colony of Connecticut, three young boys fill the house with their energy. In better weather they’ll go outside and burn most of it off. In the winter, though, they’re stuck within the four walls and those walls can press together sometimes on the two adult women inside with them.

Their mother is Margaret. Their aunt is Hannah. The boys know what the neighbors know—Aunt Hannah rules the roost.

Hannah Arnold is sister to Benedict Arnold, father of the boys and husband of Margaret. He’s often away on his mercantile business, buying, selling, and sailing goods between Long Island Sound and the rest of the Atlantic Coast.

Hannah runs the family apothecary shop and the Arnold family itself. She dispenses medicines and treatments in small quantities to customers. She pushes hard in keeping tight control over inventory stored in rows of glass bottles. She directs the upbringing of the Arnold boys. In all of it she puts more emphasis on results than relationships; on the bottoms of her shoes are usually her sister-in-law’s feelings. Hannah is also watchful of local protests and protesters, knowing that brother Benedict is a firm supporter of colonial rights and firm opponent of British power.

Sister updates brother upon every return home.

* * * * * * *

(William Franklin)

A member of another family steps forward in unmistakable fashion. Among the Franklins, Benjamin’s out-of-wedlock son William writes a speech that he delivered a few days ago to the New Jersey legislative assembly. William Franklin is the British imperial governor of New Jersey at precisely the same time his father is in England lobbying to change British imperial policy in favor of the colonies.

William Franklin publicly announces his opposition to his father’s views. Governor Franklin declares to the colony’s legislature that “you have now pointed out to you, gentlemen, two roads, one (William’s pro-imperial route) evidently leading to peace, happiness, and a restoration of the public tranquility—the other (Benjamin’s pro-colonial path) inevitably conducting you to anarchy, misery, and all the horrors of a civil war.”

In an act of leadership, William Franklin believes his duty to his followers, detractors, and undecideds is to state the case and the choice with plainness and clarity. The son and the good with the empire. The father and the bad with the colonies.

In the son’s view, that’s the choice.

* * * * * * *

The phrase on Eber Stone’s powderhorn has been recast in William Franklin’s public speech.

Also

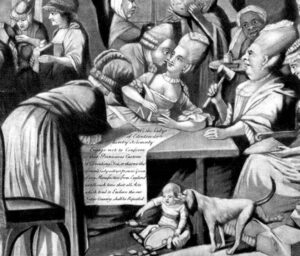

(the work of Philip Dawes)

You’ll see a kind of political pornography in today’s cartoon published in the Morning Chronicle in London, England.

Animal-faced people. A dog urinating while eating from the side of a child’s face. Racial stereotypes. A man lusting after a woman and on the verge of…doing something. Blank and stupid looks mark everyone else.

Drawn by Philip Dawes, the cartoon lampoons the women of Edenton in the colony of North Carolina in conducting their version of a “tea party” back in October.

It’s meant to convey Dawes’s belief in the imbecility of colonial-rights supporters, a very early version of “garbage”, “deplorables”, and “the 47% who don’t pay taxes”. Dawes hopes readers agree.

Today, 250 years ago.

* * * * * * *

(Walpole)

Horace Walpole is a wealthy, educated English aristocrat who likes to criticize everyone else. He’s in rare form 250 years ago as he invites a friend to visit him but please, Walpole begs, don’t talk politics if you come.

“I don’t want you to come and breathe fire and sword against the Bostonians.”

Not like “the inflexible Lord George Germain (a pro-imperial member of Parliament)”…

“or to anathematize (criticize) the Imperial Court and all its works, like the incorruptible Edmund Burke (a-colonial rights member of Parliament) who scorns lucre, except when he can buy a hundred thousand acres from naked West Indian native for a song”…

“I don’t want you to do anything like a (political) party man. I trust you think of every party as I do, with contempt…all perhaps will be tried in their turns and yet, if they had genius, might not be mighty enough to save us—from ruin or other I think nobody can, and what signifies an option of mischiefs?”, meaning every option is a bad one.

Walpole states that General Thomas Gage, currently imperial governor of Massachusetts, is being set up to fail and take the blame. Talks are already underway for British General William Howe to replace Gage, according to Walpole.

Don’t talk of any of this, Walpole advises his potential guest. Let’s just have a good time and leave the politicians to flail at each other.

* * * * * * *

(today’s descendant and namesake, of the business world)

In the vicinity of Horace Walpole is Edward Tilly, a London-based bookseller and printer. Tilly wants more than a good time.

“The Proceedings of the American Congress give great satisfaction, to all the friends of Civil and Religious Liberty in this Country (England).”

Unless the imperial government changes its course, Tilly continues, “a—the most dreadful of all Calamities—Civil War may close the Scene.”

If the people of England could vote on what to do, they would vote in favor of the colonists, predicts Tilly.

* * * * * * *

Not sure if Walpole or the cartoonist would agree.

For You Now

Wine pours into a glass. Give it a minute.

Okay, now I’ll pick it up for a sip, and for a conversation with our people in today’s Redux.

Eber Stone, what is exactly the meaning of your powderhorn phrase “My King and Country I’ll defend”?

Thomas Johnson, will your desire to innovate need to account for political changes?

George Washington, could anything make you change your mind about the child Roger West?

Hannah Arnold, do you have any worries about your brother Benedict’s character?

William Franklin, how many people do you think are still unclear about the stakes involved in the current crisis?

Philip Dawes, Horace Walpole, and Edward Tilly, how far will you go in asserting your viewpoint as the most accurate for today, 250 years ago?

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: is your life right now narrowed to a funnel?

(Your River)