Americanism Redux

February 29, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

This day is your gift. Your gift of an extra day, Leap Day.

We all know that time is a truly valuable thing in life. A Leap Day is like a few golden coins in your hand.

So, what’s your plan for the spending? An extension of the day before? A thing new and different?

Peek into their pockets. How did they spend the golden coins of their today, 250 years ago?

* * * * * * *

For him to know any greater joy than right now is impossible. Can’t be done. John Adams is likely at his happiest as a human being on this earth, today 250 years ago. Near Braintree, colony of Massachusetts, Adams is at peace at Peacefield.

(the aptly named Peacefield)

For a man with storms in his heart, that’s saying something.

At this moment, at Peacefield, he stands on his family’s homeground and homeland and homeplace from back in his childhood and even before. And now he owns it, today, having paid 440 shillings for fifty-three acres (thirty-five attached to the house, barn, and sheds with another eighteen in meadowed pasture). But his joy is not in the numbers. Much, much more for him are the memories made from emotions, passions, and feelings that come with the soil, the grasses, the rocks, and the red cedar trees that this sanctuary shares with the Holy Land. The sound of its modest water is music to him: the brook “beautiful, winding, meadering…always delighted me.”

How will he spend his gold coins of the day? He’ll answer joyously: “I must ramble over it, and take a View.”

Decades later, as clouds of another war and revolution darken far away on an American horizon, a restless fellow traveler, Henry David Thoreau, will write of an Adams-like love of “rambling in the woods” around Walden Pond.

* * * * * * *

Waiting for feedback from John Adams today is Mercy Otis Warren. She’s thirty miles away in Plymouth, colony of Massachusetts, from where her latest poem to John and his wife Abigail. She takes the Adams’s reviews, especially John’s, very seriously. She won’t seek to publish the poem if John replies with criticisms. Nevertheless, Mercy is hopeful and optimistic about his reaction to this poem that she wrote in honor of the Boston tea-dumping. She wants to celebrate that day from ten weeks ago when, in her telling, bravery, courage, and restraint appeared in a uniquely American way. Her words include: “The Heroes of the Tuskeraro Tribe,/Who scorn alike, A Fetter, or a Bribe,/In order Range’d, and waiting Freedoms Nod,/To make an off’ring, to the Watery God.”

(Mercy’s home in Plymouth, where she awaits feedback)

She places in the center of her poem the Native-disguised people of action, these persons and their dress fused as the moment’s central players. It’s her way of signaling the wholly un-imperial nature of protest and resistance. She also refers to the importance of women in endorsing the event before its occurrence. They are Americans, she suggests, the feathered men and the approving women.

How will she spend her gold coins of the day? The assent of John and then her poem formed in the joining of black ink, alphabet-shaped metal, pressed and folded paper, and finally in the hands of newspaper readers.

* * * * * * *

Abiel, pronounced Ab-bee-yul and the namesake of his father, wasn’t among the disguised Natives at Boston harbor but he agrees with the dumping of every shred of dried tea celebrated in Warren’s poem. Abiel Chandler Jr is 32 years old, a resident of Concord in the colony of New Hampshire. He’s husband to Judith Walker. They have a 6-year old daughter. He is a local tea protester.

People around Concord know him, like him, trust him. Abiel has done a bundle of work for Concord’s town government—earning money for surveying land for building a church and laying a road, counting people in the administration of local services, and teaching classes at the town school. Two days ago, his presence and reputation around town have produced an honor for him. The ninety-man Second Company of Concord Militia voted him “Captain.” That’s how militia units select their formal leaders, by vote.

(militia voters)

Today “Captain” Abiel Chandler searches for a book that he knows he must read. It’s a copy of the “A Plan Of Discipline For The Use Of The Norfolk Militia Exercise”, the 1768 edition. The book, written and published in England, is a how-to manual for volunteer officers like himself. He can read about how an officer salutes and behaves, the best ways to train men in marching as a company, and instructing his unit to serve with other companies in coordinated firing and maneuvering. The Concord militia practice for a day every six months or so, a required duty for males between school-age and elder-age. Normally, training-day is as much for socializing and partying as it is for volunteer-soldiering. But Abiel Chandler knows that the tea dumped by disguised Natives in Boston and burned by he and his fellow protesters in Concord has altered the normal.

How will he spend his gold coins of the day? A little extra reading time if he can find a copy of the “Norfolk”, which are suddenly being advertised for sale.

* * * * * * *

Speaking of “leaps” today, that massive, elevated rock ledge over there along the Chicopee River is called “Indian Leap” after a group of Nipmuc Native warriors jumped into the river to escape colonial soldiers almost a hundred years ago. And now, a few miles from century-old Indian Leap, a group of people vote with a loud collective “Yes!” and said that this rock and everything else around it is now theirs and they are now Ludlow—the people of Ludlow who have chosen to break apart from Springfield in the colony of Massachusetts and become their own new town. They are Ludlowians, hands raised to make it so, today.

(Indian Leap rock)

How will they spend their gold coins of the day? Writing the name “Ludlow” on town documents with a new spirit and excitement. And Indian Leap? Well, the past behind the rock won’t change but the future in front of it already has.

* * * * * * *

In almost every break-up there’s one who wants to and another who doesn’t. And if the break-up involves a disputed ownership and freedom in a place far away, the disagreement can get tense, bitter, hostile.

Must be England and its American colonies, right?

Try again.

Today 250 years ago, Zebulon Butler stands along the Susquehanna River. He is a native and resident of the colony of Connecticut two hundred miles east of his location. He’s also an ex-ranger from the French and Indian War, having spent a winter fighting in Native-like ways. With a small group of people around him, Butler declares that this place will be called “Wyoming”, which, he further declares, is an extension of Connecticut by way of “ancient” agreements and commissions. Not so!–according to the counter-announcement by the governor of the colony of Pennsylvania, John Penn, in a document he publicizes at the same time as Butler’s declaration. This is Pennsylvania’s land and not Connecticut’s, retorts Penn, as he orders local sheriffs and other authorities to seize Butler and his band. Penn states that the rogue group failed, among other things, to “…prosecute their claim before His Majesty in Council (that’s George III and his Privy Council and Cabinet in England), the only proper place of decision.” Back in Connecticut and still on this day of announcement and counter-announcement, a commentator known as “Connecticutensis” writes a newspaper report that urges readers to look more deeply into Butler’s interactions with Connecticut’s colonial legislature. The writer’s implied message: something smells bad there.

(later look at Wyoming valley)

How will these conflicting parties spend their gold coins of the day? By straining to peer into the minds of people aligned against them, their motivations of opposition, defiance, and protest.

* * * * * * *

The quarrels about a Pennsylvania river valley are the quarrels along the Carolina coast. Today, 250 years ago, sixteen people in Charleston, colony of South Carolina have served on a grand jury and are releasing their findings about Charleston’s quality of life. The difference between the quarrels of the two places is that the one is aspiring while the other is existing. The one is a town not built and the other is a town built and enduring.

The presentment from the Charleston grand jury is scathing.

Street lamps are smashed without anyone finding and punishing the perpetrators. There aren’t enough watchmen to patrol the streets and reduce crime. Speaking of watchmen, and constables, their wives are grabbing up liquor licenses and selling drinks with no regard for public safety. Public water wells aren’t the proper depth. Too much time is being allowed for mortgages and deeds to be recorded and fraud is rampant. Counterfeit money is everywhere. Stolen goods are for sale on every corner. A con man named Gordon pilfers money whenever he wants and all over town; he victimizes black and white alike. And free black people must start wearing a special pin on their jackets to distinguish them from enslaved black people. All in all, life’s a mess in the colony of South Carolina’s seat of government.

How will Charleston spend its gold coins of the day? On adding a new issue that transcends all of the griping for, as a newspaper described it, “every inhabitant of the Town or Country that can attend a General Meeting…is desired to do so by Nine o’Clock in the Morning, at LIBERTY TREE.” On handbills tacked to posts it was explained “every Man who has the Good of his Country at Heart, and who wishes to see those inestimable Rights and Privileges, to which the English Constitution has given him a just Claim (and which his Ancestors have hitherto preserved) is invited to attend…”

(Charleston’s Liberty Tree)

* * * * * * *

Ever met a person who just has it? The “it” factor: friendly, thoughtful outwardly and full of thought inwardly, striking in appearance, up-to-date on events, deeply-rooted in knowledge, has a great job and earns a good living, usually says the right things and does the best things. And who married a mate of similar worth.

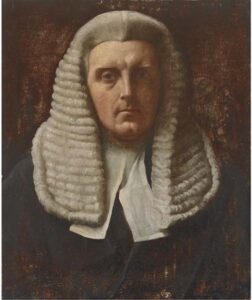

A person with the “it” factor. Richard Stockton.

(“It” is all over him)

Today, 250 years ago, Stockton has been named Associate Justice of the Supreme Court in the colony of New Jersey, his home. He’s 43 years old, six feet tall, thin yet strongly built, with sparkling green eyes, a member of the first graduating class of Princeton, possessed of a powerful legal mind, holder of a seat on the colony’s Executive Council, and wedded to Annis Boudinot, a beautiful woman who’s also one of the most prominent poets and writers in the British colonies, on a par with renowned Mercy Otis Warren and newcomer Phillis Wheatley. So impressive and so “it” is Richard Stockton that when King George III met him after the 1765 Stamp Act crisis, the British monarch nodded in obvious approval and admiration as they talked. Not many American colonists can say that.

How will he spend his gold coins of the day? For taking it all in, measured and modest, praying to do the best he can for the people of New Jersey with the gifts he’s been given.

Twenty-nine months later, he’ll sign his name at the bottom of the Declaration of Independence. Four months after that, he’ll be hauled away to a British prison as a war criminal, sliding toward death in defiance of a king who enjoyed his company.

* * * * * * *

The new day greets them as individuals with choices, into community with relations, of humanity with imperfections.

Also

The day leaps the ocean and lands in England, the mother country,…

…where the Cabinet of King George III has shut down one path that leads to judges and courts and legal rulings. Cabinet members are today in agreement that the colonial protests over tea will not be treated via the British legal system. No charges of treason will be levied and pursued. The decision leaves only two other paths available—either doing nothing in response or making the response entirely the work of Parliament, politics, and which is contained within political power. It’s not hard to guess which is likelier.

(no more talk of judges)

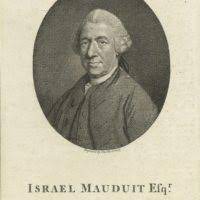

…where Israel Mauduit, an Englishman, public commentator, current member of the Royal Society, and former imperial lobbyist for the colony of Massachusetts, is frantically editing a series of articles featuring the stolen letters of Thomas Hutchison and Andrew Oliver, along with the text of the Parliamentary hearing where Benjamin Franklin was humiliated. Mauduit also rewrites portions of an earlier book he’d written, “A Short View of the History of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, With Respect to the Original Charter and Constitution.” Mauduit sees an eager London market for these writings because of British public interest in the colonial tea protests.

(he senses a reading market)

…where soon a Frenchman the same age as George Washington will be arriving after having formally been stripped of his civil rights in Paris over a contested inheritance. He is Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, talented watchmaker, harp instructor, opera composer, and all-round party-goer among French nobility. He’s also said to have poisoned wealthy women in order to gain access to their fortunes, though nothing substantiates such rumors. Beaumarchais is only days away from fleeing to England after his punishment. He’ll become captivated by the uproar over colonial tea protests. He will immerse himself in debates, conversation, speeches, and countless writings by people like Mauduit and others.

(about to discover his newest and latest passion)

The colonial rights movement will fire Beaumarchais’s imagination, leading to a time three months after the British imprisonment of Richard Stockton, when the Frenchman will order his covert French organization to secretly send weapons, ammunition, and other war materials to America in the war against the British. He will do so after learning that George Washington successfully led his troops across the Delaware River and captured British-allied forces as Stockton sits in military prison.

* * * * * * *

For this golden day it’s twenty-four hours more of reactions and plans, of perceptions and assumptions, all aimed at the western side of the Atlantic.

For You Now

Here’s the surprise—there was no Leap Day because 1774 was not a Leap Year. February 29 was the extra day they never had that year. You’ve got it and they didn’t. If today had added value to them it was the result of them adding the value. Maybe that’s the way we should live.

So what about your gold coins of Leap Day?

In particular circumstances I can hear myself saying: “if I only had more time.” Another hour? An entire day? Imagine what I could do in having more time to grapple with this problem or that issue, or to do this thing or that thing. “That’s how I would spend my new time.” Sound familiar to you?

What exactly is your focus on Leap Day—one of change or one of continuity? I’ll remind you that your answer reflects the fact that you don’t know the fact, you don’t know the outcome against which an added day seems like an added log, one more on the pile. It means the most when you don’t know the results. The extra day shines brightest because it flows to a future rather than fixes in the past.

Think of them 250 years ago. If it had been Leap Day, what exactly would be changeable in terms of the imperial-colonial crisis? What might Richard Stockton have done? Or Mercy Otis Warren, Zebulon Butler, and Charleston’s sixteen grand jurors? What would have been changeable in other aspects of their lives?

Everything locks into place and goes motionless when you know the outcome. You arrive at continuity from another direction.

My advice is to be grateful for not knowing and, from that spirit, savor the freedom of an unknown, undetermined, and unadorned future. Time yet lived is an undiscovered country. Leap the day to every day.

Hat tip to Bill the Quill Shakespeare.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider—can you pick a day that you spend heading into the future?

(Your River)