Americanism Redux

October 10, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Time is a river, and you’re at a spot in the current, 250 years ago.

* * * * * * *

Today, the massive oak and elm trees show the year with shades of yellow and red appearing amongst the aging leaves.

Today, talons wrapped around branches of the hardwoods, eagles wait and watch, beaks toward the water below.

Today, in the water and beneath the treetops, fish rise to the surface.

Today, yelling can be heard, and smoke drifts up from sounds of explosions.

The eagles fly away to quieter trees.

Bodies and musket balls splash into the water.

The fish follow the current downriver.

Today occurs the largest recorded battle of the year on the western hemisphere of the planet Earth.

It’s October 10, and the Battle of Point Pleasant is fought at the confluence of the Ohio and Kanawha Rivers.

* * * * * * *

(Hokoleskwa)

Along the Ohio, the sun dips into the trees on the western horizon. Dusk is coming.

Hokoleskwa, called Cornstalk by British colonists, lays down his war club. The Shawnee leader is exhausted. Fallen leaves on the ground cling to the end of the club. It’s sticky from a dark substance.

Hokoleskwa had been yelling in the smoke a few hours earlier. “Be strong!” “be strong!!” had been his loud call to them. He’s not shouting anymore. His force was too few, maybe 400 warriors launching a surprise attack on 1,100 enemy colonists. He had failed to gather as many warriors from other tribes as he’d expected, and the enemy had more men than he’d hoped. The plan was to use the river to block their movement, making the water a killing field while offsetting the numerical disadvantage. By afternoon’s end, he knows the surprise attack has failed. He spreads the word: retreat, fall back, abandon the ground.

The final acts are for survivors to find as many dead warriors as they can and cover them with a layer of leaves and brush and dirt. Fifty are dead; three times that number are wounded. One of the corpses covered up is Pukeshinwa, father of a young six-year old boy named Tecumseh and close friend of Hokoleskwa.

Hokoleskwa wipes the sweat from his face, cleans the war club, and slips into the forest with the survivors. In a short time he’ll return to the Shawnee village, tell his friend’s son of his father’s death, and inform the villagers of a great storm coming.

* * * * * * *

(the grandson, Clement)

37-year old George Vallandigham marches in the 1,000-man expedition led by Virginia imperial governor Lord Dunmore. The force is twenty-five miles away from the 1,100 men commanded by Colonel Andrew Lewis in the fight at Point Pleasant. Dunmore’s expedition is on track to rendezvous with Lewis and his men and drive toward the Shawnee villages.

Vallandigham is a husband, father, surveyor, and builder-owner of a ramshackle cabin on a trickling ribbon of water called Robinson’s Run, about a two-day hike from Fort Pitt. Staying alive is the best he’s been able to do; danger rises with every sun and hangs with every moon. It’s said you don’t live there, you breathe there. Vallandigham’s deepest wish is that the Virginian expedition will secure the woods.

He doesn’t know it yet but, one day, his grandson Clement Vallandigham’s opposition to the Civil War will so enrage Abraham Lincoln that the American president seeks the arrest, imprisonment, and either his execution or expulsion from the United States.

Today, though, George Vallandigham wants to know if war will continue and life can be more than breathing.

* * * * * * *

(from the school he started)

Colonel Andrew Lewis breathes easier tonight. He’s learning that the Shawnee warriors are quietly pulling back.

Lewis was surprised earlier today when he heard the shrieks and yells of an unexpected attack on his force’s encampment. He and his men were trapped against the Kanawha River. They might have panicked but didn’t, keeping calm as the Shawnee shot arrows and fired muskets toward their tents and campfires. The violence became man-to-man, hand-to-hand. Lewis had joined the fight, slashing with knife and hatchet, firing with musket and pistol. He’s soaked with sweat but not with the Kanawha’s water. Neither he nor his men had jumped into the river.

Lewis also showed his characteristic ability to think in the midst of chaos. He had the presence of mind to order a group of his soldiers down river to swing behind and counter-attack the enemy from the rear. The movement succeeded. The enemy retreated and left Lewis’s force in control of the battleground.

He doesn’t know it yet but, one day, Lewis will be one of the founding trustees of a school that will later become Washington & Lee University, with ex-Confederate General Robert E. Lee as its president after fighting against the American president who hated Clement Vallandigham.

* * * * * * *

One side flees homeward. They will think about their enemy’s next move, toward them, and what the possibility of utter and total destruction will mean. The other side halts and restores. They will plot a course westward, in pursuit, to demand possession of vaguely-defined lands.

Also

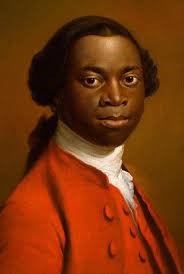

(Charles Ignatius Sancho)

45-year old Charles Ignatius Sancho is casting the first vote by a black man in a British parliamentary election. He owns property, qualifying him to cast a ballot. He’s been free since running away from an enslaver at age 20. The 2nd Duke of Montagu at Blackheath taught him to read and write and, afterward, Sancho opened a small shop as a free man. In addition to composing music, he also began writing in favor of abolitionism and is now well-recognized in the British anti-slavery movement.

His vote is a wall-buster.

For You Now

(Point Pleasant)

And so it came, a battle. From the tensions and individual clashes that had marked the upper Ohio River valley since spring, a formal battle was waged at last. Virginia’s British imperial governor and the people aligned with him had pushed hard against Natives. They believed a victory in battle would serve their side. Finally, one of the tribes would be pushed no more. Battle, and victory, happened.

The forces led by Dunmore and Lewis are yet to join together but the prospects for such a joining seem likely. From there, further success by the imperially-led Virginians has a similar inevitability to it.

In hindsight from the yellowing and reddening trees, the line feels and looks straight and clear.

But does this line and this moment connect to anything else that hasn’t happened yet, anything bigger? In this case, the British-imperial crisis rages along most of the North American coast while the Battle of Point Pleasant is being fought. Does the one connect or interact with the other?

At a future date, will we be able to look back to this moment and place and see some straight and clear line from then to now and from now to on-ahead?

Or will the line curl and turn into itself, a path leading nowhere except to its own termination, a destiny of destination.

All I can tell you is this: the river still flows by Point Pleasant.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: are you looking back to earlier in the year, to the spring perhaps, and seeing a clear and straight line from then to now?

(Your River)