Americanism Redux

November 21, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

You know it because you live it. Others know through living, too. And pretty much across the board you and they have the same feeling.

Here it is:

—the problem is so big right now that it’s likely this turns out only one way:

—war:

—that’s the reality for you and me if we were alive today, the 21st of November, 3rd week of November, cusp of late November:

—250 years ago.

* * * * * * *

(Ipswich)

Well, it was a helluva meeting.

Zero. That’s the number of attendees at the Ipswich town meeting who voted AGAINST a set of actions in support of the recent special Congress that met in Philadelphia. Zero. One hundred percent unanimity (ever been in a meeting like that?) behind the economic boycott and the outreach to the people of Canada. Mouth, meet money.

But there’s a lot more to it. They also were one hundred percent in favor of beginning to enlist men in a local military unit AND to draft a contract for building “a house for the Encouragement of Military Discipline.” Blood, meet guts.

The family of Michael Farley attends the meeting. They’re ecstatic at the outcome and the one hundred percent unanimity. When the new military unit convenes, they’ll be in the front row. When the new building goes up, they’ll be first inside, ready to fight, ready to serve, ready to teach, ready to learn.

* * * * * * *

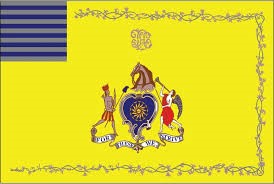

(their flag)

Strutting their stuff in Philadelphia, that’s what the new “Light Horse of the City of Philadelphia” is still doing today, 250 years ago. This most innovative community in North America has seen Abraham Markoe—a Danish immigrant, born in the Danish colony of St. Croix in the Caribbean Sea—organize the cavalry unit earlier this week. He sees war on the horizon and wants to fight British rule. He’s a successful landowner and merchant in the town. Markoe’s equally wealthy friends and colleagues are paying a steep price to join the new unit, furnishing horses and all equipment. Markoe and his peers know each other well as members of numerous social organizations. They’re turning social ties into military bonds.

* * * * * * *

(Warren lives at X)

Joseph Warren, living in Boston, has spoken to people who’ve left an impression on him. He’s talked with some of the Massachusetts delegates sent to the special Congress in Philadelphia, which had adjourned last month. They’re “in high spirits on account of the union which prevails throughout the Colonies—it is the united voice of America to preserve their freedom, or lose their lives in defense of it.”

Warren sees that same spirit in 260 members of the “Provincial Congress” gathering in Boston to govern the colony of Massachusetts as they deny and reject British authority. They are “an Assembly of Spartan or ancient Romans” in their ardor, zeal, and steely determination. Warren hopes that Boston “can live without Government until we have some further intelligence of what may be expected from England.” But this uneasy stability can’t and won’t last forever, and Warren worries that “disputes and quarrels often arise between the (British) Troops and the inhabitants.”

His somber conclusion: “It is barely possible that Britain may depopulate North America (in a war), but I trust in God she never can conquer the inhabitants.”

* * * * * * *

(the grave of Dade)

Across the colonies letters are spreading that are identical in outcome but different in wording. Townshend Dade, a Christian minister in Alexanderia, in the colony of Virginia, has such a letter sitting on his desk today, 250 years ago. The letter-writer asks Dade to contact people about a meeting that will occur to crystallize local participation in the upcoming anti-British economic boycott. Dade will distribute the information via churches in the town. Dade has a rather poor reputation here—he’s accused of frequent drunkenness and sexual advances on married women—but he knows he should comply with these instructions. He doesn’t want to risk offending the letter-writer, George Washington.

Scores of other towns up and down the Atlantic Coast are arranging similar meetings, though hopefully without Dade-like shadows complicating the news.

* * * * * * *

(the doors will be locked here)

Check the box and on to the next task, and the next, and the next, and the next. Box-checking is all Robert Carter Nicholas is doing these days. He’s the treasurer of the colony of Virginia and also an active supporter of colonial rights. He’s in the middle of the biggest pile of work he’s ever seen—the upcoming economic boycott of British goods will keep him up at nights with all the headaches of enforcing the thing. The boycott was the result of the recent special Congress that met in Philadelphia.

One checked-box has nothing to do with the boycott but deserves attention nonetheless. Nicholas marked it as “done” a few days ago. He sent a letter to a Christian minister about the final closing of “the Negro School” in Williamsburg, colony of Virginia. Its only teacher and administrator—Mrs. Wager—had died a few months back. The school still has money in its account, though not enough to stay open. Nicholas inserts into the envelope a note, a “check” if you will, worth 11 pounds, 17 shillings, and 2 pence, British currency. Account closed and school shut.

And far much more is ended as well. Nicholas’s letter points to the lack of a market of donors, a lack of motivation to help, a lack of urgency in reversing the fortunes of this particular school.

A boycott is coming. Behind it, a war is looming. Above it, futures suspend as the present unfolds. Inside of it all, the black children in need of education will no longer learn at Bray School.

* * * * * * *

(a leader’s problem)

Speaking of suspensions, Matthew Tilghman in Annapolis, colony of Maryland, is increasingly nervous today, 250 years ago. He’s the formal leader of a “Provincial Assembly” called in Maryland to help govern the colony in this suspended state between rejected British authority and not-quite-known next-step to replace it, reform it, or, God forbid, revolutionize it.

The nervousness of Tilghman comes from the fact that he’s not seeing many designated members of this “Second Provincial Assembly” (the first was four months ago and fully attended) arriving for the session.

Is momentum for colonial rights in a state of suspension altogether in the colony? Is it something else?

Tilghman will need to decide, as a leader, what to do if more members fail to show up in Annapolis.

* * * * * * *

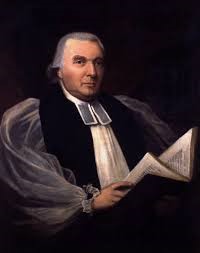

(the farmer-minister)

A Christian minister-posing-as-Farmer has written a long essay for sale in print shops and newspaper offices throughout the northern colonies. The first edition hit the shelves five days ago. Perhaps “A Farmer”—who is Reverend Samuel Seabury in reality—can shed light on the extent of momentum. Maybe Tilghman will be a reader.

Seabury’s “Free Thoughts on the Proceedings of the Continental Congress” is powerful.

Farmer-Minister Seabury denounces the Congress for having betrayed British colonists in this critical moment. He blasts the decision to use a far-reaching economic boycott as a tool for lowering imperial-colonial tensions. They’ll do the opposite, according to him. Item by item, provision by provision, Seabury pounds his argument home.

He also rips the Congress for having suppressed alternative views and dissenting opinions. “The arts and stratagems used on this and some other occasions, during the session of the Congress, together with the caballing out of doors, and the unfair dealings within, will fill up more pages, than are comprehended in the present Letter to my Fellow-Farmers.”

“Finis”, he writes.

* * * * * * *

(our view of the purchased island)

Here’s my money, I’ll buy the island. I like the look of the land. I can make a go of something here. What to do first? Let’s start with a tavern. Gotta get timber and workers. I need to name this place, though. How about my name?

Today, 250 years ago, Samuel Ellis buys an island adjacent to Manhattan Island in New York City.

Ellis Island, where a tavern sits for a while and, generations on, more than twenty million immigrants will land.

* * * * * * *

(terror)

Around midnight, in the last minutes of today, 250 years ago, a group of men are terrified.

Mouths filled with the taste of salt water, clothes soaking wet, bodies cold to the bone, and worst of all, unable to remember any other time in their lives as awful as this moment, they hear the roar of night-black wind, angry explosions of lightning bolts, the crash of ocean waves against their wooden vessel, the cracking and splintering of the tall masts that would power them back home to Salem, colony of Massachusetts.

The men of the brig Polly pray they can survive to see the dawn.

* * * * * * *

The war of weather on the ocean recedes. The war of people on the land is yet to begin.

Also

(the monarch in military regalia)

King George III writes to Lord North, his prime minister in Parliament. “New England Goverments are in a state of Rebellion,” he judges, “(and) blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this country or independent.” George III has been mulling who to assign military command over the effort to crush the rebellion. He has a person in mind: “Major General (James) Gisborne is the best qualified for the particular Service.”

Gisborne had political connections as well as some experience with colonial issues in Ireland, another site with discontented people.

* * * * * * *

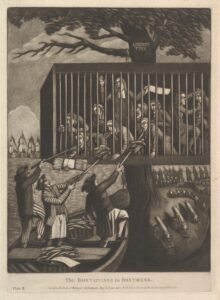

(Dawe’s work)

In London, political cartoonist Philip Dawe has published another scathing drawing of the imperial-colonial dispute. His ridicule of the protesting colonists leaps off the page.

He places ten men, dressed as Puritans, into a cage suspended in a “Liberty Tree”. They are force-fed whole, uncooked fish and cry out for help. One of them stands as he wails, holding a quotation from Psalms in the Bible. In an attempt to help themselves, one of the men holds out a bundle of “Promises” tied up together. British Redcoats watch the scene from the background while rows of cannon surround the tree. Jailors sneer at them from below.

A glance tells you the colonists are vile, weak, desperate.

If you’re King George III, you believe Major General James Gisborne can deal with it easily.

* * * * * * *

(Lagrenee’s work)

“Sold!” Ah, a glorious word to the French artist L.J.F. Lagrenee, 45-years old and a resident of Paris.

He looks to find the new owner of a painting he made—sorry, created—about five years ago. It’s his version of the story of the Roman god of war, Mars, and the Roman goddess of peace, Venus.

“The Allegory of Peace.”

Love, sex, luxury, tranquility.

The buyer is Nicolas Francois Jacques Boileau, art dealer and curator, as well as an artist himself, with deep connections in the French aristocracy. Perhaps he’ll send the painting to one of his primary clients, a former general and military advisor to the deceased French king.

* * * * * * *

War and Peace, eternal tensions in an earthly world.

For You Now

The thing just seems unavoidable at this point. This is where people are, 250 years ago today, at this state of mind and opinion.

That thing is war.

It’s an odd combination, when you think of it. The present is chocked full of unknowns, half-knowns, wrongly-knowns. The future, however, appears as the time that seems much more knowable and concrete—war is in the offing and unless x or y or z happen, war will be the reality of daily life.

As I’m writing this to you and for you, a thought just flew into my head. Which of the two works of drawing are the most outlandish and other-worldly? Is it Dawe’s cartoon or Lagrenee’s painting? Which strikes closer to this day 250 years ago? Maybe they’re closer in spirit than a glance shows.

Look closely at the painting. It feels to me like Mars is about to leave the bed, shoo away the doves, and pick up the gear…

…for that thing called war.

Forgive the digression.

We’re seeing in today’s entry a variety of reactions and stances in light of a looming war. One is preparatory for war (the Farleys, Markoe, Warren, George III). A second is preparatory for a measure that stops short of war (Dade and the dozens of organizational meetings to launch boycott-enforcement). A third is uncertainty of status (Tilghman). A fourth is blame-naming as part of directional course-changing (Seabury). And fifth are the people whose lives are part of the storms around them and have to navigate the outcomes (the purchaser of an island called Ellis, the former students of Bray, the crew of the Polly).

The more I reflect on this, the more I’m convinced of the need for our discernment in working in and around the undecided, the unresolved, and the unknown. Slow it down, think it through, sort it out.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: are you particularly drawn to one of these three as the best term for right now? The undecided, the unresolved, the unknown.

(Your River)