Americanism Redux

November 16, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

Below the written lines are the other lines. The other lines are separators between the life we believe we lead and the life often led, the life of darkness. These other lines are thin, all too thin, though we seldom bother to notice. Until, that is, the other lines snap and wave in the wind and we descend into the life we thought people no longer live.

* * * * * * *

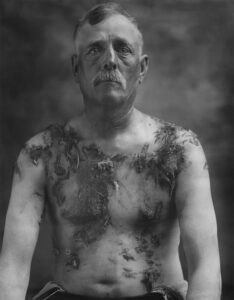

When he takes off his shirt, you can see it. The skin is still reddish in color and sensitive to the touch. He’ll tell you that each day the pain lessens. Likely he’s telling you the truth. What he might not say, however, what he might not yet know how to say, is that other pain gets a little worse each day. It’s the pain of people who yell at him, ridicule him, humiliate him on the streets of Boston in the colony of Massachusetts. Their words enter through his ears and burn his brain.

He is 49 year-old John Malcom, a one-time employee in the British customs agency from Falmouth, Massachusetts (now Portland, Maine). A few weeks ago he’d been tough and zealous in enforcing British trade regulations with a local merchant and boat-owner. A fight broke out with Malcom being seized and then, with his clothes still on, tarred-and-feathered and pushed through the streets as a public display of the real weakness of British imperial power. Since then, Malcom had come to Boston and found himself in the middle of the frenzy over the oncoming ships filled with East India Company tea. Anti-tea crowds know Malcom by sight and by story and they are merciless in their treatment of him today, 250 years ago. He’s approaching the breaking point.

When heated to boiling, tar burns up the skin. A thick and heavy odor rises into the nostrils. A scream is loud yet muffled in the scalding temperatures. Smoke, steam, and an invisible hiss wrap around the human being in torture. The poured tar coils around arms and legs, neck and torso.

(example)

* * * * * * *

As Malcom glances with furious eyes out his window, a group of Boston residents meet to finish their petition. They’ll deliver it tomorrow to the Boston selectmen (town council). In the petition they’ll demand the public resignation of those people in Boston who have agreed to serve as tea consignees—those who will accept, sell, and distribute the tea. The petitioners will require the resignation to be visible, in the open, for all to not simply see and hear but to witness. Dwell on that: to witness.

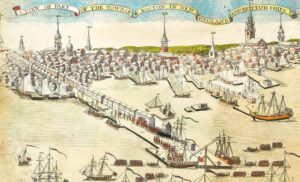

(Boston)

* * * * * * *

James Parker is 45 years-old and a well-known Scottish merchant in Norfolk, colony of Virginia. Today, 250 years ago, he’s trying to focus on business issues, with no success. Instead, his public duty as a member of Norfolk’s common council absorbs his mind. He’s picking up all the signs through his eyes and ears—bitter words, loud arguments, scowling faces. He’d been on one side of it back in 1765, having helped craft the pro-colonial rights and anti-Stamp Act strategy and actions in Norfolk. That’s no longer true.

Now, he knows the other side of the line. He’d gotten pulled into a ferocious dispute in Norfolk over smallpox inoculation. He’s a pro-inoc guy and that stance nearly killed his pregnant wife and left their house in ashes. The anti-inoc crowd turned on him and attacked the Parkers and their home. The bitterness between the pro-inoc and anti-inoc sides compelled Parker to invest some of his business profits in a new ropewalk, or company that transforms hemp into rope. His ropewalk is known in the town as Scottish and in favor of British imperial rights. The other ropewalk operation in Norfolk is owned by “buckskins”, or people who believe in the colonial rights movement. With hard feelings that clash over inoculations and ropewalks, Parker walks through Norfolk’s streets and see the lines of community stretching thinner by the hour.

(James Parker)

* * * * * * *

Like a phoenix, out of the ashes, re-born and re-living. That’s the best way to describe the handful of “Sons of Liberty” groups that have again emerged in Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and a dozen other small communities in the British colonies. While they’re active and robust this week, they had first appeared in 1765, the groups that served to enforce and give actual power to anti-Stamp Act demonstrations. Sometimes they slipped into violence, sometimes not. Many of its participants were military veterans of the French and Indian War. The groups are reconstituted, with hold-overs returning from 1765 and newcomers joining now in 1773. In Boston, for example, some of the Sons will overlap with the Committee of Correspondence and with the group that is completing the petition for tomorrow. They’ll walk a line between restrained protest, inspired resistance, and activated violence. The thin line.

* * * * * * *

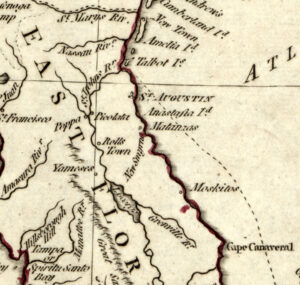

A recent memory haunts Paola Lurance, a resident of New Smyrna, a British colonial settlement on the Florida peninsula. She is from Greece but lives now in New Smyrna, supposedly an indentured servant but in reality an enslaved woman. An overseer had demanded that Paola have sex with him. When she refused, the overseer beat her viciously with a board, across her back, shoulders, arms, legs, and stomach. She screamed that she was pregnant. The overseer didn’t care and the beatings continued for several minutes more. Three days after the horror ended, Paola gave birth to a dead baby.

The line in her mind between dreams and nightmares vanished. Tonight, as they do every night, the nightmares run freely when the candles go out.

(where Paola lived)

* * * * * * *

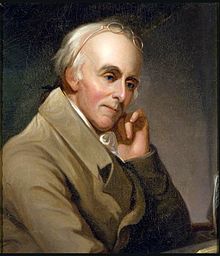

Dr. Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia medical doctor and community innovator, publishes an essay today 250 years ago. He writes, “I venture once more to take up my Pen in behalf of the poor African. Great Events have often been brought about by slender Means.” Rush observes that enslavement is declining in the British colonies in America, a trend that appears to be global.

Is the line between enslavement and freedom tilting in liberty’s favor?

(Rush)

Also

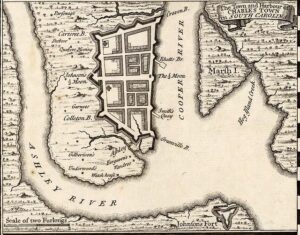

Today, 250 years ago, a newspaper shows the existence of readers and listeners. Told in the Gazette’s printed lines on four pages, the life and living of people in Charleston, colony of South Carolina, cross and re-cross one another. They stitch a portrait, a drama, a world unimagined except by those who know it each day.

How hard is this world to see from the vantage point of the future?

(Charleston)

* * * * * * *

–Want something fun and out of the ordinary? There’s a specialist who walks the high wire. Buy a ticket and see him ignore risk and defy fear. You’ll be thrilled and entertained.

–The same disease that killed so many cattle a few years ago is back again. Keep close watch on the cows and report any sign of the disease. If we can’t control it, we stand to lose money, food, stability. An important part of the local economy is on the verge of disaster.

–Understand that the latest reports tell us of remarkably similar stances toward the ocean-going tea; people in New York City, Philadelphia, and Boston are all calling for the tea to be refused when it lands in port. The shared outlook is cause for marvel and reason for optimism.

–Reports of rebellions by enslaved black people are arriving from St. Vincent’s Island and Honduras; mahogany cutters have fled Honduras out of fear they’ll be killed and are resettling in the colony of Georgia.

–Buy or sell enslaved black people, or come to the Work House to sort through the last group of enslaved people who don’t appear to know their owners’ names and have been seized and kept there until someone claims them.

–Learn more about the mysterious life of the Chinese people, including their rigid social system, the power wielded by a small group of people, and the dim prospects for greater freedom and liberty to be found there.

Today, 250 years ago, the people of Charleston in the colony of South Carolina plod through another ordinary day.

For You Now

That line between.

What and what?

Civilization and barbarism. Peace and war. Upset and outrage. Disappointment and discontentment. Vice and virtue. Tolerance and intolerance. Acceptance and rejection. Restrained protest and organized violence.

They’re not all opposites, are they? Some are differences of degree. Regardless, they share a line of dividing, of separating one from the other. And of indicating when a crossing or switching has occurred.

They also join one thing to another thing, a common wafer-slice space not much different in size and scale than the present tense of time that tells you when the past was and when the future will be. Always razored, tracked in seconds and measured as minutes.

These lines are everywhere.

You jump the line when impetus or stimulus strikes.

You glance back at where you were.

You set your feet on where you are.

You see ahead, where the new line awaits.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: as an American, have you crossed a line this year?

(Your River)