Americanism Redux

May 30, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Now is new.

(yes, it is)

You know and feel it. Not everything is new, of course, but a whole lot of important stuff seems on the verge of new. Turn your head and take a look. Focus your mind and apply your thoughts. Listen to the sounds around you.

What was will be so no longer. New is here.

The new may not have been planned or welcomed. The new may not be fully formed. The new may not be done.

Still, the new begins, and you start to find how new and old fit together.

* * * * * * *

(Colonial Williamsburg)

What in the world is happening in Williamsburg, colony of Virginia? A tornado? A hurricane? A fire?

Something else.

Over the course of the prior 168 hours—7 days—the new crashes and bashes and booms its way through the colonial capitol town’s brick buildings, cobblestone streets, and clapboard structures.

Okay, forget weather images. Imagine instead a row of dominos placed in a line. Think big dominoes—tree-trunks big. They start falling, one by one.

Remember the small group of legislators who planned to seek a government resolution for a June 1st day of prayer and fasting in recognition of the Boston Port Act?

Here goes.

May 24, Virginia’s colonial legislature had passed the June 1 resolution. They added to it new plans for a June 1 parade to be led by the Speaker of the House solemnly carrying a tall metal scepter—a mace—in front of the marching crowd in civic tribute to the colony’s elected government. Domino falls. These decisions of May 24, in turn, had angered Governor Lord Dunsmore who, to the total unawareness of his sleeping house guest George Washington, decided during the night of May 25th to disband the Assembly and send the elected members home on May 26 as punishment. Domino falls. From there, in reaction to Dunmore’s dismissal of them, 89 outraged legislators met on the 27th in the Raleigh Tavern’s Apollo Room and declared: first, we are now our own “Patriotick Assembly”; second, a political attack on one colony is a political attack on all colonies; and third, let’s convene a general colonial congress to plan further. Domino falls. Later in the evening, a smaller Apollo Room-subset of 25 legislators voted to ban East India Company products. They also hosted a supper dance, which included the governor’s wife (!), to show their orderliness, civility, and commitment to decorum. Domino falls. On the 28th a still smaller set of members comprising the Committee of Correspondence dispatch to their Boston colleagues a written record of the three “Resolves” from the 27th . Finally, on the 29th Boston’s Circular Letter arrives asking them to do everything they’ve already done over the prior six days.

Dominoes down.

What has taken months and seasons and, really, years to grasp, clutch, and stitch together as consensus and shared views—single threads flying in the wind—is done in Williamsburg in less than a week. And think of location: in a place far away from tea shipped or dumped or targeted for retribution.

The thing seems unthinkable and incredible. Mind-blowing and head-shaking.

It is new.

* * * * * * *

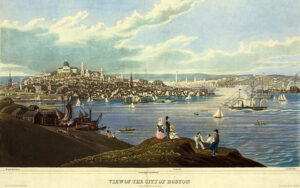

(Colonial Boston)

People in Massachusetts also see the new. They take immediate action.

From the shadows, two large sets of folks quickly appear. Numerous merchants, business owners, and traders write and sign a letter to the departing royal governor, Thomas Hutchinson, replaced by General Thomas Gage. They thank Hutchinson for his service and offer words of encouragement. Then they get to their ask and their point—after landing in London, they urge him, please begin to help improve the perception of Massachusetts by talking to Parliament’s members and changing their minds about the colony. Lawyers and judicial officials write and sign a separate letter to Hutchinson, saying much the same thing. Implicit in both letters is the reality that the Boston Port Act punishes the innocent along with the protestors. These local letter-signers and their families support England and imperial power but are still hurt by the Port Act.

Meanwhile, a third group rushes their ideas onto paper and into the hands of General Thomas Gage, Hutchinson’s replacement-successor. This is “the petition of a Grate Number of Blackes of this Province who by divine permission are held in a state of Slavery within the bowels of a free and christian Country.” Raw emotions fill the parchment page—we cannot marry, we cannot parent, we cannot worship, we cannot get equal benefit of the laws, and we ask for enactment of legislation that gives each enslaved black person his or her freedom at age 20.

New moment. New governor. New proposal. New threshold of imperial-colonial crisis.

New.

* * * * * * *

(the Hitchcocks)

Inundated with these writings, the colony’s new governor has barely time to find his quarters before being notified of a new book that awaits his attention. The Massachusetts legislature has printed Reverend Gad Hitchcock’s sermon from May 25 in honor of the annual election of the colony’s Councilors, who serve as a board of executive advisors to the governor and “upper house” to the larger legislature. (Neither Hitchcock nor anyone else knows that Parliament had just decided to make the Council appointed instead of elected. That shock is still coming.)

Hitchcock’s sermon emphasizes the people’s role as judges of good and bad government and the conduct of members of government. Hitchcock describes the best government as that which mixes the powers of a single ruler with those of representative bodies. He also declares that the people possess the right to transfer power from one part to another if circumstances require. Above all, Hitchcock states, God “is the great patron to liberty and benefactor of the world.” God is the source.

It’s a new time and in the dark-clothed minister’s eyes, the red-coated general needs tutoring in the political culture of Massachusetts.

* * * * * * *

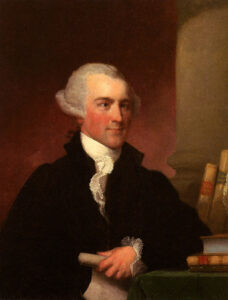

(Josiah Quincy Jr)

Like Gage, Josiah Quincy, Jr receives a type of Boston tutoring in late May.

A prominent, vocal, and active leader of the colonial-rights cause, Quincy has written and published a pamphlet entitled “Observations on the Act of Parliament Commonly Called The Boston Port-Bill, With Thoughts On Civil Society And Standing Armies.” After dissecting the evils of the act and the military sent to enforce it, Quincy writes: “America has in store her Brutus and Cassius—her Hampdens and Sydneys—Patriots and Heroes who will form a band of brothers, men who will have memories and feelings, courage and swords, courage that shall enflame their ardent bosoms, till their hands cleave to their swords, and their swords to their enemies’ hearts.” Quincy’s is a new and open willingness to use violence.

That is too much, too galling, for an unsigned letter-writer called “Well-Wisher”, who responds with a written warning to Quincy. Those who follow you and listen to you, Well-Wisher asserts, will one day no longer commit violence against the empire but against you and you alone. They will riot and pillage you as you’ve had them riot and pillage others. The Cromwell you seek will destroy his seeker.

The new takes a new turn of its own.

* * * * * * *

(Wheeling Island, in the war zone)

The new and real war is in the Ohio River valley. Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore has unleashed agents and envoys to seize ground claimed variously by the colony of Pennsylvania and the Cherokee and Shawnee tribes, among other Native groups. Dunmore’s primary war-driver is Dr. John Connolly, who has organized 100 “active men” to march west along the Ohio River toward Wheeling. Connolly wants a fort built at the junction of the Ohio and the Kanawa Rivers. He denounces the Shawnee as “haughty, violent, and unthinking” who must be “thoroughly chastised and convinced of their insignificancy.” He urges war with no limit. Colonel William Preston, a land surveyor employed by George Washington, observes that two men tasked with plotting land boundaries along the Ohio are missing. Preston asks in a letter to Washington that he inform Virginia’s Governor Lord Dunmore. If Connolly learns of the missing men, he’ll have his own response.

This new has no end in sight, no sign whether it will clash or connect with the imperial-colonial crisis along the eastern coast.

* * * * * * *

(James Duane)

The new will find its way and the way could reach into areas of life you might not expect. Like law.

James Parker grapples with an old legal case, Mann v Ashfield, a long-standing inheritance dispute in the colony of New Jersey. He seeks an infusion of energy—a new force—might push the disputants into a settlement. He hopes a new ally, James Duane, a New York lawyer, can help nudge them along. Duane has experience in handling such cases that grow from months into years. Parker knows Duane is balancing his private legal practice with his increasing concerns about the imperial-colonial crisis. Duane’s loyalties toward England appear to be weakening as his wife Mary Livingston Duane and her family exert influence on his views. They’re pro-colonial in a legal world stiff with British precedent.

John Adams is again in Ipswich, colony of Massachusetts, meeting with fellow lawyers to continue deciding about new judges. The candidate most favored by the “Liberty men”, as Adams puts it, seems likely to be chosen by the group for a judicial position. The next step is to question the candidates and themselves on their legal views about fraud, debt, trade, and the powers of sheriffs. The replies will reflect British law and jurisprudence. Yet as the sun rises today, May 30, 250 years ago, Adams only wants to return home to his sick wife and children. A fear for their lives fills part of his mind as the discussion over judges echos in the tavern.

* * * * * * *

The new that no one knows can leave a life unrecognizable.

Also

(Ann Lee)

On a ship in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean is a woman who, at times, breaks out into dance or jolting shakes of her body. She’s a Quaker, but of a distinct type. She is Ann Lee and the people who criticize or condemn her call her a “shaker.” Ann Lee is westbound, leaving England for the colonies, leaving a land where she was persecuted and heading toward a land where she can find a place to worship as she pleases. The small group of people with her want to do the same.

* * * * * * *

(home of the Olivers)

In the country left behind, in England, the Earl of Dartmouth, one of King George III’s ministers dealing with colonial affairs, has appointed Thomas Oliver to be the next lieutenant governor of the colony of Massachusetts. No relation to the Olivers already in the colony, Thomas Oliver comes from a wealthy enslaving family in Antigua. No one knows it now but Oliver will be history’s final royal appointment in the colony of Massachusetts.

* * * * * * *

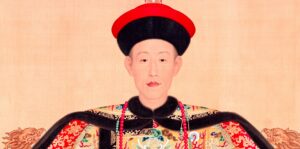

(Qianlong)

Qianlong is the 73-year old emperor of the Qing dynasty on mainland China. He has ordered the destruction of all printed books that support sedition, dissent, and treason. Of course, he defines those terms in light of himself. Today, provincial governors are busy looking through stacks of hand-written books for review.

* * * * * * *

(Abiodun, center)

Abiodun is the new ruler of the Oyo coalition on the southern side of the African hump. He’s finished piecing together the alliances he needs in order to hold and use power as ruler. The delicate work of personal diplomacy isn’t strange to him—he is skilled as a professional trader and merchant. He’s considering how best to use the trade and exchange of enslaved people to greatest advantage as part of the local economy. As Abiodun puzzles over the issue, civil war has broken out inside Oyo by late May.

George III. Qianlong. Abiodun. Three human rulers who share a dislike of the same new—which is any new threat to their power and authority.

* * * * * * *

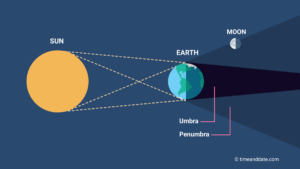

(crooked line)

Today, May 30, 250 years ago, at approximately 10:30pm, the three celestial bodies of sun, earth, and moon form the uneven line of a penumbral lunar eclipse. The planet of people separates a source of light from a reflector of light.

And the new comes again.

For You Now

(earthrise, a different new)

The occurrence in Williamsburg staggers me. As I wrote above, so much time had been needed to gain inches of careful progress in the ideas that bind people together and now, suddenly, in under a week, an explosion of aggressive thought and bold action. Their efforts on behalf of colonial rights were actually ahead of what Boston’s colonial-rights supporters had wanted. And don’t forget the geographical context of Virginia’s removal from the tea ports of Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and Charleston.

That’s truly the new in this week. It may be showing us a hard shift in the gravity of the moment.

I’d like you to think about a pair of news (as I’m using the word right now) from today’s Redux.

First, the explanation for Virginia’s fast emergence is a combination of quiet organization and basic fundamentals. It’s clear that organization can be effective in the shadows and silence. We’ve not seen or heard much from Virginia in the last several months, though without doubt they were not strangers to each other or to each others’ ideas. In addition, the connection of ideas rests on the importance of fundamentals in the how, who, why, when, and where of governance. They perceived a danger to fundamental rights and liberties, and action ensued. Organization without fanfare and an understanding of the most time-tested aspects of life and living vaulted Virginia to the fore-front in this moment of the new. Anything from our era strike you?

Second, defined areas of space can and do affect the course of events. They are more than drawn lines and printed names. Virginia isn’t Massachusetts and the Chesapeake Tidewater isn’t New England. The ideas and habits, the things tried and kept and tried and discarded, have deep yet distinctive impact from one area to another. It’s the truth withering into the trite which results in no one caring. But you need to step back and scrape off, especially when the new blows in and the threads unravel and suddenly everyone cares. Much of what emerges as forceful and conclusive will do so from defined areas on maps, charts, and fields. There you’ll see the new.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: let’s tip our hat to the space bar and ask it this way—are you perceiving a new and are you perceiving anew?

(Your River)