Americanism Redux

May 2, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Outside, in the night, an owl hoots.

Eyes watch the meadow below the tree. Talons grip the branch until the last second of flight, descent, and attack.

Inside, in the night, they sleep.

A thin pillow folded in half. A blanket pulled up against the chilly spring blackness. In the black before dawn, the dreams come.

At early light, one by one, they rise from bed, rested, or exhausted, or unsure.

Outside, a rooster crows, sitting on the post.

This is their life, this is their world, these people of that time.

Welcome to their wake-up after the long spring night.

* * * * * * *

(the instant when he learned)

In the dawn streaks of pink and orange, he sees red. Only red. The faces of his mother, brother, pregnant sister, and the unborn baby. Dried blood on their skulls left without hair or skin. Murdered, mutilated, massacred. He is Logan, 51-year old leader of the Native tribe called Mingo, and it’s only been a few days since he learned that these members of his family had been slaughtered by Daniel Greathouse—a friend of Michael Cresap’s—and thirty white men at Yellow Creek, near the home and tavern of Joshua Baker, in the upper Ohio River valley, west of Fort Pitt. The only survivor is a two-month old infant. Logan hovers between grief and rage in the dawn of red.

The heinous incident is the worst of the past week when Natives and colonists have slashed and counter-slashed at each other. War is birthed. War is up and standing. War scans the morning woods for moving shadows in the Ohio valley. Then, sun rising, war plunges in.

* * * * * * *

(he wants to keep it fluffy)

As the early sun shines on his home in the colony of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, the governor, considers the brief remarks he’ll write to acknowledge the formal opening of the colony’s legislature later this week. He wants to keep the wording light and the tone breezy, unchallenging and comfortable. He’s waiting for updates from agents, activists, and representatives—men like Dr. John Connolly, men like the Cresaps and their friends—on latest actions and developments in the valley of “beautiful river”, the O-e-o to the French, or Ohio to the British.

* * * * * * *

(these plants)

Elsewhere in the Virginia morning, Thomas Jefferson remembers to check with the enslaved men and women who work his extensive vegetable gardens. He’ll want them to keep close watch today over newly planted “white beets”, or Swiss Chard. May’s morning chill disappears quickly but not always quickly enough. Jefferson knows the young plants need warming soil, warming air if he wants the picked greens for eating in a few weeks.

The plants have a small shadow in the early sun.

* * * * * * *

(hold it up to the light)

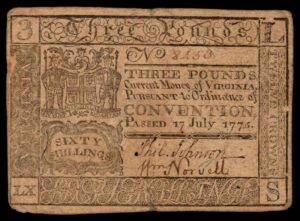

The light of a candle might not do it. Let’s go outside and hold the paper up to the sun. See anything suspicious?

That’s what some men and women who aren’t Jefferson are saying this morning in Virginia. They’re skeptical of the latest printed currency, fearing counterfeiters have already started making and circulating fake duplicates. The fear is so widespread that Robert Carter Nicholas, the colony’s treasurer and a colleague of Jefferson’s, has written a public declaration to explain ways for ensuring the new currency is real.

Use the day’s light to reveal the trustworthy as well as the worth of trust.

* * * * * * *

(stop here on the Freedom Trail)

How long has the sun been up?

Too long to suit Benjamin Edes and John Gill. They’re partner-printers, having worked together for the past nineteen years to crank out editions of the Boston Gazette and Country Journal. Today they work like fanatics—which some say they are, fanatical, that is, in their support of colonial rights—though at this moment their fanaticism is to get today’s edition of the newspaper onto Boston’s cobblestone streets. Today’s especially.

Edes and Gill are running a page-one article and a special, separate supplemental edition on one topic, one issue, one man—Alexander Webberburn, serving in London as Solicitor General of the British Empire. The page-one article is a first and fresh reprint from a British newspaper, a piece written three months ago in England by “A Bostonian”, a line-by-line dismantling of Wedderburn as hell-bent and devil-inspired on leading the destruction of colonial rights and liberties. If anyone is wondering about what to do, “A Bostonian” helpfully includes an answer—a specific description of philosopher Adam Ferguson’s roadmap of justified revolution. And the special supplement newspaper? Well, Edes and Gill fill it with only articles and essays about Wedderburn. Their readers know exactly who they should see as the engine behind the intensification of the colonial-imperial crisis. Wedderburn.

In addition, and directly in the self-interest and civic-interest of Edes and Gill, the printers insert a striking notification about the proposed “New American Post Office” which now has subscribers from Boston and other towns. It’s a brand-new network for circulating information about American issues, viewpoints, and constitutionalism.

Before boys rush today’s edition out the door of their printing shop, Edes and Gill tuck into the content the following item, a matter of regular record: “Burials in the Town of Boston since our last, Eight Whites, Two Blacks, and Baptized in the several Churches, Seven.”

Sometimes it’s those early casual moments of the day, while the coffee heats on the stove and before the meetings and planned events, that can say a lot.

Edes and Gill take a moment for a breath of relief. Good. Done. The newspaper is out the door, into readers’ hands, onto tables and desktops. And it’s a prime day for sitting in the sunlight and reading the newspaper.

* * * * * * *

(some of Joseph Johnson’s work)

Edes and Gill’s sigh of relief isn’t the norm for Joseph Johnson of Farmington, colony of Connecticut, south of the Boston printing shop. He tends to groan. He shakes his head in sorrow. He can smile and grin but an instant later he might close his eyes and grimace.

Johnson sees the morning sun and thinks of scalding heat and blinding light.

He is a Native convert to Christianity, now an evangelist preacher among Native people. To him the past is an immense burden, the future found on a harrowing path. Guilt hunts him, setting traps in dark places, luring him into a spiritual ambush rather similar to the human horror inflicted upon Logan’s family on Yellow Creek.

Johnson writes this early sunlit morning to his mentor and ministerial guide, the Reverend Eleazer Wheelock of Dartmouth College in the colony of New Hampshire.

Poured forth on the parchment meant for Wheelock is Johnson’s self-description of his torment and pain and his sole and single savior in Jesus Christ. Johnson’s emotions harken back to New England’s greatest evangelist and Wheelock’s fellow religious thinker, Jonathan Edwards, author of such works as “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” The letter by Johnson echoes Wheelock’s learnings and Edwards’s teachings.

Also in Johnson’s letter is a candid confession. He’s flat-broke. Out of funds. He’s spent money on operating a Christian school for Natives in Connecticut and helping to maintain Native followers in seven of the colony’s towns. A further cost came in the trip he’d taken to see renowned British leader Sir William Johnson (no relation) at his sprawling estate in central region of the colony of New York. Joseph Johnson wants to return in September to William Johnson’s impressive home because the British leader is, arguably, the single greatest imperial influence on Native tribes west of the Hudson River. Johnson the evangelist hints at a delicate network of Native tribes, spanning thousands of miles across vast river valleys and Great Lakes who might be brought closer to the hybrid creature of Christianity and Anglo-American-Northern Euro/Protestant ways. It might change the world or it might collapse in the first hard wind.

A solitary evangelist, battling guilt, sin, poverty and holding hope, mercy, gratitude. Truly, as a Hebrew monarch once wrote, there is nothing new under the sun.

* * * * * * *

(John Morton)

A sweet sun shines down on 50-year old John Morton. This son of Finnish immigrants isn’t given to dramatic flourishes. Still, he’ll certainly take his moment in the sun to feel the warmth on his face. After a minute, though, it’s back to work and time to move on.

Morton is on his third day of new service in the colony of Pennsylvania. Third of a thousand.

Governor John Penn has appointed Morton to be a justice on the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. Morton is now also “justice of oyer and terminer and general gaol delivery.” These significant judicial posts are in addition to his years in the colony’s elected legislature and in the sheriff’s office. Morton’s reputation is that he’s a hard worker without rival, putting in long hours on writing proposed laws, collaborating with other legislators to build coalitions that enact them, and drafting communications from the legislature to the executive, the governor. Morton is a believer in colonial rights; he served in the Stamp Act Congress called during that crisis of 1765-1766. Morton is a leader of experience, of extraordinary merit and caliber.

If current difficulties continue between the British colonies and the British imperial government—which, given their direction of late, would almost have to mean that they worsen—Morton’s understanding of leadership will be of immense value.

The sun of this beautiful early May day gives a brilliant shine to the white paint of the Pennsylvania State House, the workplace of John Morton.

The same striking appearance is visible two blocks away, at Carpenters’ Hall.

(Carpenters’ Hall, keep it in mind)

Also

(not far away from her lover)

At the French royal palace in Versailles, France, Madame du Barry dresses in her favorite morning gown. Her hair is carefully arranged as she sits in a chair and reaches for a cup of coffee offered her by a young black servant. That’s the pose the painter wants. It’s captured, brushed, dabbed, and stroked, on canvas.

A short distance away at the palace her lover, King Louis XV, seems to be recovering. Suffering from bad rashes and a high fever with small pustules over his body, the doctors had finally given their verdict: smallpox. The king had not gotten smallpox before and so had no immunity built up; neither had he received an inoculation of smallpox, a controversial practice that yields good results of survival. Regardless, the fever has dropped, the rashes apparently lessened, and the pustules, well, maybe they’ll shrink in time. It was scary for a time, but now? A corner turned? Perhaps. The sun moves and the time tells.

* * * * * * *

(Whitehall Pump)

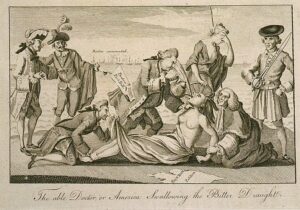

(bitter draught)

There’s nothing sunny about scathing political cartoons on this day. In London, England, a pair political cartoons are in circulation. One is “The able doctor, or, America, swallowing the bitter draught.” The other is “The Whitehall Pump.” Both cartoons depict a wicked and stupid imperial government inflicting misery upon colonial subjects. Both, fascinatingly, depict a female Liberty and a female Native. Both cartoons also use the liquid poured from an elevated position, forced into the mouths of suffering victims. The images shrink the issues. Don’t have time to know the people and arguments? Need a way to sum them up? No problem, see the visual.

* * * * * * *

(North, focused on the task at hand)

Cartoons be damned.

Lord North stands in the House of Commons and declares that the proposed Massachusetts Government Act is necessary because the colony is “in a distempered state of disturbance and opposition to the laws of the mother country.” This bill, the second in response to the tea dumping after passage of the Boston Port Act, must be adopted.

Now.

While the sun still shines.

For You Now

(a sunrise imagined)

I research and write these Redux entries with my best effort at unknowing the future. Obviously, it’s not possible and I fail (whiffs of Joseph Johnson?). But I think it’s essential for me to have this spirit in how I produce the entries. You likely understand why—the people living then had no idea of what the actual future was. We have a habit, maybe more unconscious than otherwise and much more powerful than appreciated, of sweeping in future reality to their lived reality and then proclaim we’ve studied the history. To do that is just not fair and nothing less than hubris.

Some of these people have clear and powerful plans, no doubt. They think they see a future. And whether life ultimately proved them right is, to me, beside the point. They didn’t know they would be right. They were acting like it, hoping for it, striving toward it. But that’s not the same as living it under the sun in the present shadow.

They get out of bed after a night’s sleep or rest or silence. They turn and face into the day ahead. You’ve done that already as you’re reading these words. You’ve got plans and expectations to a degree, right in some moments and wrong in others. You live them out minute-by-minute as the future dances and skips just out of reach.

Look at the jumble of life on this day 250 years ago. Among it, war has started for Logan’s family and many others in the Ohio valley, a villain-sounding Wedderburn is held up for view, a leader called Johnson struggles to prepare for summer and fall, and another leader named Morton tackles a new position of responsibility (we’ll see him again and you can thank me now for it—he’s one of the most important Unknown Founders). And excuse me, though, for again touching on that little set of words framed up by Edes and Gill, the racialized tally of the newly dead coupled with non-racialized number of the newly baptized. Stats all, people not.

Sun comes up, sun goes down.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: have you been surprised by anything on a national level, community level, or individual level since waking from last night’s sleep?

(Your River, sun-rised)