Americanism Redux

March 7, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Husband and wife. Parent and child. Friend and neighbor.

Do human relationships get any more basic than these?

You don’t want them to shake or tremble. You don’t want them to crack apart and break down. But across the table, across the room, across the fence, something seems to be happening. A split opens up.

Relationships under pressure. Under assault. Under cut. It’s today, 250 years ago.

(life)

* * * * * * *

(son)

The Greenoughs show a splitting in relationships in the colony of Massachusetts. With quill pens dipped in frustration, Thomas the father and John the son exchange letters, arguing and counter-arguing over the last-resort tea dump in Boston and the mysterious disappearance of shipwrecked tea off Cape Cod. Thomas the father praises the final form of the protest and applauds the Native-disguised protestors. They are virtuous, he asserts. John the son disagrees, vehemently, seeing disorder in the floating leaves and chaos in the floating chests. Those protestors chose a fitting costume, in his view, clothed and yelling like savages. The Greenoughs’ dispute isn’t ordinary. It cuts to the basic understanding of individual rights, individual security, individual freedom. The split between father and son is deep and growing. The chasm needs a bridge but the Greenoughs dig furiously into the darkness.

* * * * * * *

(Margaret’s husband)

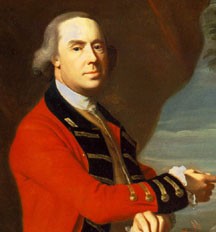

In Boston, British General Thomas Gage rubs his eyes. He’s got his tall black boots on. Some days they fit nicely, some days tightly. Today, 250 years ago, it’s an uncomfortable tightly-fitting day. Across the room, his thick red officer’s coat hangs from a peg on the wall. Tired, he sits in his chair, conscious of the wooden frame. Feels good. It’s been one of those weeks.

He’d hosted a meeting with colonial protest leaders, including John Hancock and Dr. Benjamin Church. He implored them—pleaded, if you want to know the truth—to not make this week’s March 5 anniversary of the 1770 Boston Massacre more than it should be. Gage knew a crowd would gather, maybe near Faneuil Hall or Old North Church to hear a speaker lament the four-year old downtown clash that left five colonists dead. Gage was honest in his meeting with the protest leaders: he feared the effects an over-the-top speech could have on Bostonians tense and on-edge over the tea protest and the coming imperial reaction. The splits were already occurring and the wrong kind of speech would widen the gap. Please, Gage says, take it easy on them and on all of us.

At Gage’s home, his wife Margaret Kemble Gage, born as a colonist herself, hopes her husband won’t be drawn into a dispute with the people she calls “my countrymen.” If he is, she’s not certain about her own choices.

* * * * * * *

(what they’re commemorating)

And why is Gage rubbing his eyes?

Because John Hancock blew the doors off.

John Hancock was the speechmaker, Dr. Samuel Cooper may have been the speechwriter, and witnesses recorded the crowd’s reaction to the March 5 anniversary speech.

Hundreds of Bostonians listened with tears in their eyes, breaths of sorrow, and mournful clasping of hands. Hancock ripped the British for the day’s debacle four years ago. He denounced the Redcoats for poisoning local culture, especially the youth. He railed and wailed about tyranny and despotism and the denial of human rights. He placed the current mess in a worldly context of Athens, Rome, Persia, Turkey, France, and England. And he called forth the strength and support of heavenly guidance.

Which means that today Gage in Boston sits listlessly in his chair and hundreds upon hundreds of people in homes in and around Boston are sitting in rage and anger around their fireplaces. Some sit in worry and fear. The space of splitting widens in the frozen ground.

* * * * * * *

(she’s the driver of the two)

A complex family relationship is cut in Boston today. Phillis Wheatley mourns the three-day old death of Susanna Wheatley, her co-enslaver, whose corpse is now buried in the frozen ground. The complexity is obvious—Susanna and her husband paid money to own the life of a human being, a young girl from west Africa. Susanna then recognized the girl’s gift for learning and creativity, educated her, and sponsored her emergence as a poet and writer. Finally, she and her husband freed the now-teenaged Phillis, who is the talk of Boston whenever anyone can stop arguing about tea. Phillis is grateful for Susanna’s kindness and mindful of Susanna’s part in the slave-holding world.

The splits often produce more questions than answers.

* * * * * * *

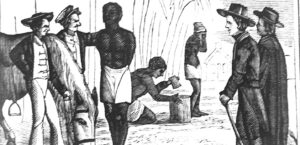

(what some are trying to stop)

A question is raised for the third time elsewhere in Boston. Members of the colonial legislature of the colony of Massachusetts are today discussing the latest version of a proposed legislative bill that will “prevent the importation of negroes, and others, as slaves to this Province.” It was offered in 1767, and failed. It was offered again in 1771, and failed. Will the colony’s legislators devote time and energy to the anti-slave trade bill? Not clear. They’re huddling together in frantic conversation about imagined British imperial reactions to the tea-dump. When they change topics it’s usually for equally frantic self-talk about their own virtue, unity, and worthiness. That’s us, right?

Time will tell if issues can have relationships like people have relationships—will liberty and freedom of colonists join hands with liberty and freedom of enslaved people?

Or will eyes, looking across table and room and yard, see someone different staring back at them. The best hope is that people, jointly caring, join the issues as a pair.

* * * * * * *

(a typical CofC meeting)

John Thurlow sees things differently in New York City, that’s undeniable. A wealthy merchant and trader who first earned money from the fur trade, he’s leading a meeting of the city’s Committee of Correspondence (CofC), the group belonging to a network created to share and spread news about British imperial policies dangerous to colonial rights in America. It’s strange, though. Back in 1765 with the Stamp Act crisis Thurlow was as radical a protestor as there was in New York City, a member of the activist group the Sons of Liberty. But now, he’s seeing it differently, not sensing the same attitude within himself. He manages to convince his colleagues on the CofC to support a six-point statement that seeks to delay the calling of delegates to a general congress to meet to address the current crisis. First it was “Mohawks” and now it’s a Congress? Wait a minute. Stand down. Let time work for a while. See what the imperial government will actually do. Don’t call for a general colonial congress and we don’t have a fundamental authority to make governmental decisions. The CofC agrees with the six points.

Thurman exhales with relief after the vote.

But in the faces around him, Thurman has seen trouble. And he can easily build a scenario in his head where the split erupts into view among his colleagues. To him and them, it’s not 1765 anymore, though they’re taking different routes out from the past. He wonders how many of those men around him on the CofC will hold for restraint when the ground gets slippery and ice thaws to mud.

* * * * * * *

(Daniel Campbell, one side of the transaction)

North of New York City, in Schenectady, colony of New York, Daniel Campbell has learned that Colonel Philip Schuyler is paying money owed to people who have provided services to the colony’s imperial government. Schuyler is a member of the New York colonial legislature. As a wealthy man, he has expertise in the financial side of the colony’s government. He oversees payment of the government’s bills. He’s also the future father-in-law of Alexander Hamilton.

Campbell writes to Schuyler that he’s owed sixty-found pounds in British currency for goods and services rendered to the British Crown. A messenger will collect the money.

Today’s letter is an ordinary economic transaction, much like those now being analyzed by the Scottish Adam Smith. Unknown to either Campbell or Schuyler is the depth of loyalty each man possesses toward competing ways of law, justice, rights, and liberties. A source of splitting exists in their relationship, invisible to them now, though taking tangible shape week by week. Allegiance is the source and it will drive them further apart.

* * * * * * *

(the envisioned outcome of the project)

In Kingston, colony of New York, about seventy miles south of Schenectady, a board of trustees has convened to discuss their exciting project for the town. It’s the opening of a new, free school that will teach practical subjects to students, blending academic knowledge and applied learning. The only problem is that the school is set to open in early May and no one on the board has heard about the hiring of teachers and the overall condition of classroom space. It’s been five months since instructions had been given to address both topics.

The board is nervous about the timeline on paper and the five-month silence on the ground. They’re trying to hold themselves together as a unit to ensure that this worthwhile project gets done. The relationships between them will be tested by the strain of project completion. But what if other strains arise? The biggest barriers to opening the school may have nothing to do with the school itself.

* * * * * * *

(the origin of Washington’s word choice)

George Washington can’t shake the feeling that the lands and settlements he’s envisioning under his control in the Ohio River valley are not securely in his possession. He knows that talk of a vast anti-colonial Native alliance has been brewing in the region, ranging from tribes in the Wabash, White, and Miami River valleys all the way south into the Appalachian Mountains. More than that, Washington’s nervousness extends to British imperial policy-makers in London. “I am not without my fears,” he writes, “that we may yet meet with some rubs before this matter is finished.”

His concerns pertain to a group of British officials who show a particular animosity and vengeance toward colonists in America. It’s the relationships that are already split and broken that occupy Washington’s mind.

* * * * * * *

(you have to judge how far it’s gotten)

“…before this matter is finished.” The phrase signals the future arrival of actions that can jolt the course of the present. The feeling is the defining trait of this winter’s last weeks. But even before the actions appear—whatever they may be—relationships are stretching taut at home, work, and community. Can they go thinner without snapping, further without splitting?

Also

(a boy’s homeland)

Today, in the Diablo Mountains of southern California, a small Native boy clad in a long, soft leather shirt, talks with villagers about his unforgettable adventure from yesterday. The boy had been walking on his own along a rocky path in the craggy landscape of the sierra. To his shock, he found himself staring at three or four strangers—soldiers—who spoke a language he couldn’t understand. They seized him and dragged him back to a larger group of thirty or forty other strangers. The boy was terrified, thinking he would never see his family again. Suddenly, his father had appeared from among the rocks. The Native man struggled to communicate with the strangers, but finally convinced them the boy was his son. The strangers talked with each other and agreed to let the boy and his father go. The reunited father and son didn’t know that they had just met the Spanish exploratory expedition of Don Juan Bautista de Anza on the 662nd-mile of their trek from Sonora to Monterey, the first-ever land passage made here by Europeans. Anza calls this place Santo Thoms, a name unknown to the son and father.

* * * * * * *

Today, in a palace called Buckingham, a 36-year old man sits on a royal throne in long robes, carefully woven clothes, and a golden crown, and watches one of his advisors—clutching a document—bow and back away from the monarch’s chair. The monarch is George III, the advisor is the Earl of Dartmouth, and the document contains the king’s words written down. The document includes: “unwarrantable practices…violent and outrageous proceedings…subversive of the Constitution there…put an immediate stop to the present disorders…to be established for better securing the execution of the Laws, and the just dependence of the Colonies upon the Crown and Parliament of Great Britain.”

It is the king’s announcement that the House of Lords and House of Commons are to act, forthwith, to quell colonial protests, especially in Boston and Massachusetts. Next step, the legislators do their work and finish the project.

* * * * * * *

(media outlet)

While Dartmouth reads the British monarch’s statement aloud to members of Parliament, a media outlet “Public Advertiser” reports in London that a fleet is being outfitted, possibly “to reduce the mutinous Spirit of the Americans.” The “Public Advertiser” has also printed a long statement written by “Fabius”—a fake name taken by Benjamin Franklin, who’s still in London—asserting “that the Americans should be obedient or subject to the King of Great Britain is a Position in which all Parties seem to be agreed, but that the Americans are Subjects of Parliament or the People of Great Britain is not so generally allowed.”

* * * * * * *

(one side of the transaction)

A ship has just departed from London carrying a small box sent by Edward Dilly. Dilly is a local bookseller and he’s written a letter to John Adams, a customer and one of the protest leaders in the colony of Massachusetts. Dilly has discovered they share more than product and price; they are compatriots of liberty and freedom. Dilly has inserted into the box a newly published book, “Political Disquisitions”, by James Burgh. “I flatter myself that you will find much pleasure in the perusal,” writes Dilly, “His ideas of Government are very just and clear, and many useful hints may be gathered, which may furnish sufficient matter for the establishment of a New Government upon a solid foundation.” Dilly adds his reassurance that he thinks it won’t come to that; the British government is too mired in debt to afford tough counter-measures against the protests. And after all, Dilly concludes, if I were in charge, we’d “pursue such Steps only as will conciliate the affections of the Colonies to the Mother Country…”

“Our Interest like that of Husband and Wife is reciprocal, one cannot be hurt without the Other’s being equally injured.”

* * * * * * *

Tell that to the Gages, the Greenoughs, to countless other families. Relationships are groaning under the pressure of a rough late winter.

For You Now

(it builds)

Relationships. We see the blood, the bond, the transaction and exchange that separately or together form the basis of relationships. They are in all time and spaces and places. Your life is the living of relationships.

Relationships always have pressures. The pressures change or continue. But the fact is that the pressures are, in and of themselves, a constant. Ever-there.

Redux shows us the nature of relationships in a condition of distinct pressure. Concerns and contemplation over the most fundamental forms of living together is not your ordinary condition. And when events, actions, decisions, and the rest mount up, when growing amounts of life fills up with these elements, pressure rises as compression builds.

Your life is, like Redux, more than speeches and laws. We absolutely see that in 1774. We’re not signing a document in Independence Hall, actually more than two years away from it. Yet again in similarity though in different stretches of time, your life and Redux are entering an extended period when it’s clear that the pressure will intensify. Think for you: the presidential election and the period between your present and that future. Think of them: the formal imperial reaction to the tea protests and the period between their present and that future. An outcome is guessable but not knowable. In-between are your relationships.

Relationships will come under stress—strained to the point of splitting. Put your energy not in avoidance but in maintenance. Tend them with time. And when you feel frustration, take a page from Gage’s book and regain composure in a comfortable chair. We’re on the journey to American Founding in Americanism Redux.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: looking ahead, where are your relationships strongest and where are they weakest?