Americanism Redux

June 27, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Boil it all down and one thing is left, stark and clear.

You are the linchpin.

Just think about it. You’re right now, in this single and very real moment, the present. You’re the thing between the past of how you’ve gotten here and the future of where you’re likely going. You’re the linchpin in this instant.

Others also? Sure. But you especially? Absolutely. And don’t forget it.

* * * * * * *

(imagine him with a smile, and that’s his today)

At this moment 250 years ago, he’s joyous, bubbly, cup running over with optimistic energy. You haven’t seen that many days like today in the life of John Adams, 39-year old attorney from Braintree, colony of Massachusetts. He’s been selected to be one of the colony’s delegates to the proposed General Congress, now scheduled for late summer in Philadelphia.

He’s comparing the coming “Assembly” there to be like a Greek conclave, a wise court, an ancient gathering of geniuses, a Jewish “Sanhedrin”, “a School of Political Prophets…a Nursery of American Statesmen.” He won’t measure up to the brilliance of the participants—he’s certain of that—but “I hope to be there taught.”

“May it thrive, and prosper and flourish and from this Foundation may there issue Streams, which shall Gladden all the Cities and Towns in North America, forever.”

He wants to make this an annual get-together with different people having the chance to serve as delegates so as to educate the entire “grand March of Politics.” It would also ensure that the same people serving as delegates surrender their money-making opportunities outside of public life; rotation frees them up to gain wealth. He suggests that mothers teach their sons about politics because “I suspect they understand it better than we do.”

From his position of today, 250 years ago, Adams the linchpin sees a glowing light on the horizon of the future.

* * * * * * *

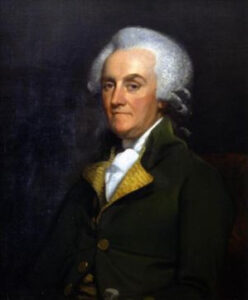

(Richard Henry Lee)

Richard Henry Lee is another linchpin of today, between his past and his future. Writing in sum-up mode, he describes to a family member staying in London about how things have gotten to where they are in the colony of Virginia.

“We had been sitting in (Virginia’s) Assembly near three weeks when a quick arrival from London brought us the Tyrannic Boston Port Bill, no shock of Electricity could more suddenly and universally move—Astonishment, indignation, and concern seized on all. The shallow Ministerial device was seen through instantly, and every one declared it the commencement of a most wicked System for destroying the liberty of America, and that it demanded a firm and determined union of all the Colonies to repel the common danger.”

Lee as linchpin retells of a slow-moving yesterday that explodes, uncovering a tomorrow of glorious and severe clarity.

* * * * * * *

The clarifying explosion has placed one of Lee’s neighbors in a troubling position.

He is Edmund Randolph, 30 years old, son of a father, nephew of an uncle, caught between two sadly divided parts of the same family.

Father John Randolph is convinced that the colonial rights movement is flawed, impulsive, and dangerous. More than that, he’s decided to push his view into public debate and contention. He’s writing a lengthy pamphlet that he’ll publish under the title of “Considerations on the Present State of Virginia”, which, if left unchanged, will result in disaster in the opinion of Edmund’s father, John.

Uncle Peyton Randolph is less than a month after his stirring march at the front of a solemn parade down one of the main streets of Williamsburg. He’d carried a sceptor that people recognized as a special artifact of Virginia’s legislature. He was fiery in his support of Boston, of Massachusetts, of colonial rights. To stand down in the face of new imperial laws was, in his mind, a betrayal of the colony.

Pulled today in opposite and irreconcilable directions, Edmund’s is a family without a linchpin.

* * * * * * *

(the Prescott house)

Abigail knows the words. She has helped conceive them, rather like the only child of her and her husband, William. Abigail knows of right now—the linchpin—and the words the volunteer group from Pepperell town, in the colony of Massachusetts, have just voted to approve in this spot of the world. She, husband William, their son William Jr., the Prescotts join with like-minded residents of Pepperell today, in this linchpin-present moment to write and record “the united vote” in favor of anti-imperial “resolves.”

The past they see behind them: the British actions against them taken by people “who carry on their wicked designs as if by magic art assisted…”

The future they see ahead of them: embodying for all of “North America” their pro-colonial rights’ actions of “laying aside all contentions, broils, and even small quarrels, and to omit the practices of every thing that tends to disunite us as brethren, as neighbors, as countrymen that are interested in one and the same chosen cause, and united stand, or fall together.”

* * * * * * *

(site of the Hermitage)

He’s back, exhausted and truly worn out. What a welcome sight is home, which he’s dubbed The Hermitage in Queen Anne’s County, colony of Maryland. Matthew Tilghman arrives at his plantation. A beautiful set of horses pull his carriage over a bed of crushed stones and shells. The driver tugs on the reins and Tilghman’s carriage stops. You see the linchpins in the wheels as Tilghman steps out of the carriage.

It’s been a strange set of four days for the bewigged Tilghman. Ninety-six hours as the presider, moderator, and umpire for ninety-two members of the Maryland…what are they exactly?…governor-dismissed Assembly, governor-disbanded Assembly, ex-legislature, provisional legislature, or something else? Whatever the title—and it’s important to come to an agreed-upon title because that will send all sorts of signals—Tilghman has sat at the head table as the formal leader of the group. They’ve been striving and straining to agree on what to do next as a body elected to serve in the colonial government but now without a colonial governor who acknowledges their existence, their powers, their purpose, their role.

So, they improvise.

By today, the ink is dry on a set of “Resolves”. Each county in the group gets one vote whenever they choose to meet as a body. For now, they’ll select a Committee of Correspondence—also, in reality, serving as a sort of executive committee—and they also name their delegates to the “general congress” meeting later in the summer in Philadelphia, supporting Boston without question and sending supplies to its residents, while accepting an economic boycott of Britain if the meeting in Philadelphia decides to go in that direction.

Tilghman arrives back at The Hermitage in a carriage pulled by horses. The driver pulls back the reins and brings the carriage to a stop in front of the house. Tilghman steps onto the crushed stones and shells, his enslaved man-servant waiting for him. For a moment, the linchpins joining wheels to axels can be seen. Seconds later, the driver signals to the horses to move and the carriage rolls away.

* * * * * * *

The Strawberry moon of June tells Benjamin Chew that it’s time he and his wife Elizabeth move to their country house. Most of the year they live on South Third Street in Philadelphia, colony of Pennsylvania. When summer comes, though, the heat is unbearable and they move three miles to the northwest, to Cliveden, in Germantown.

Chew is glad to breathe a cooler air. The year is barely half-over and it’s been a challenging time. He’s decided to give up his position on two local land-related political offices, the Recorder (of deeds) in Philadelphia town and the Master of Rolls (of deeds) in Philadelphia county. He’d done with them. Bigger than that, however, is his decision to terminate his private law practice, which severs his ties with such clients as the Penn family, the wealthy and well-connected Quaker clan that controls governance of the colony. Chew’s decision suggests he knows that the imperial-colonial crisis is reaching a boiling point much hotter than the Philadelphia summer. He’ll keep what’s nearest and dearest to him—his reputation as one of the greatest legal minds and law practitioners in all the colonies.

Ah, he breathes in the sweet air of Cliveden, where he gets away from it all.

He doesn’t know that in three years, during the Hunter’s Moon, British Redcoats will be firing their muskets from inside Cliveden, dead and wounded Americans will be outside strewn around the yard, and American cannon carriages will be pulled up and blasting away next to his cherished home. And he will be jailed on suspicions of favoring the British, wrongly as it turns out.

Smoke will conceal the linchpins.

* * * * * * *

(Pettit’s boss)

Charles Pettit has sent the orders to the sheriff of Somerset County, colony of New Jersey. Pettit’s boss wants to know the sheriff to count the number of people living in the county and the number of houses in the county. Why? Taxes, most likely. Anything else?

That will be up to Pettit’s boss, Royal Governor William Franklin of New Jersey, a man deeply devoted to the King of England, to rule by monarch, and slightly less to his father-out-of-wedlock, Benjamin Franklin, still living in England.

Pettit looks back: the last time this order went out two years ago the sheriff did nothing.

Pettit looks forward: get the count done so we can start assessing the proper tax owed.

Pettit the linchpin in-between: keeping the boss happy.

* * * * * * *

(the special flour of Mount Vernon)

The only happiness Thomas Newton, Jr has on his mind today is that of his customers or, ideally, his “constant customers.” That’s his phrase for people so enamored by eating bread made from special flour that they’ll do buy it the very first minute it arrives to the baker’s shop. Newton saw it happen, first-hand, when a baker in Norfolk, colony of Virginia, handed out fresh bread made from Newtown’s special flour a few days ago. Actually, Newton gets the flour from a supplier; he needs as much of the stuff as he can get, as soon as possible. And he knows the supplier also has access to herrings—throw in the herring, too.

There, Newton finishes his written request to the supplier, his fish-and-flour man. Scribbles the supplier’s name and location on the envelope: For George Washington, Mount Vernon.

Let’s get those linchpins spinning as fast as possible on the wagons hauling in the next shipments.

* * * * * * *

(the Clinch River)

The council is done at Lead Mine Mill Creek. Not meeting, council. It’s a different thing, especially here and now, in the midst of the brutal violence unfolding in the Ohio River valley.

The outcome is that Colonel William Christian, linked to Lord Dunmore and the colony of Virginia, is tasked with commanding 150 men to go “ranging” and “scouting” along the Clinch River valley. Their goal is to encounter hostile Mingo Native warriors aligned with Logan. They will be in full counter-guerrilla mode: ready each minute for ambush, either as target or perpetrator, which means speed, shock, suddenness, and messaging through the use of scalping, mutilation, and torture. That’s how it’s done out here, in this war of the woods.

They’ll be no linchpins in wagon or cart wheels.

* * * * * * *

You are your closest sole separator of past and future, the living connection between two tenses of time restricted to the present. A human linchpin.

Also

(built in New Orleans the year the debt was paid)

Carlos Maret De La Tour cannot believe he’s grappling with a debt older than he is. Salomon Prevost insists that he is still owed money by La Tour. Not so, says Carlos today, 250 years ago, in the port town of New Orleans, a Spanish possession for the past dozen years. Carlos states that his own father paid the debt off in 1745 with a combination of rice, potatoes, and vegetables. It’s an exotic dispute in an exotic place where Spanish, French, Creole, Caribbean, African, British, and Native meet, the most unique community in the western hemisphere.

Some of the warm waters flowing slowly through the delta were once in the Ohio, after passing through the Clinch, from the creeks and springs west out of the Blue Ridge and Appalachian Mountains.

* * * * * * *

(the scar now)

French King Louis XVI, the Count of Provence, and the Count and Countess of Artois today have sore hands, arms, and shoulders. They’ve been given the smallpox inoculation, a still controversial preventative treatment. If everything goes according to expectation, they’ll have minor scars where the pox was inserted, but no further problems from smallpox. They’ll be like the lucky few who survived smallpox though with considerable pockmarks on their faces, like a man utterly unknown to them a half-world away, the fish-and-flour supplier, George Washington.

For You Now

You get the picture by now. Linchpin. Holds two things together, often a wheel and axel.

I’ve stretched a point beyond the mechanical to include the tenses of time. Your moment in the present acts like a linchpin between your past and your future.

An important, and perplexing, aspect of it is that your present is always moving, yet always stationary. But when you think about it, a linchpin has something like that, too, always turning with the motion while it holds in place.

I’m wondering how you can evaluate the strength of a linchpin. By touch, I think, when you try to move or jiggle it to check the fit. By sight, I also think, if it’s gotten the color of rust or some evident external decay. And then you’re done.

I suspect a mechanical engineer would have more to say. There’s likely a stress test, formula, or calculation that speaks to resilience of the linchpin.

Maybe it comes down to judgment based on experience. When the linchpin has endured “x” amount of revolutions, it may be time for a change.

Interesting word in our context, isn’t it? Revolutions.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: is your current condition, as a linchpin of your present, ready for the stress of faster revolutions?

(Your River)