Americanism Redux

January 11, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Over there is your diary. Over there is a sheet of parchment paper. Over there is a notebook.

But you’re not writing in any of them today, 250 years ago, unless you’re in the south, where it’s warmer.

For most British colonists, it’s deep winter. Ice. Snow. Frigid air. And there sits your ink bottle, which someone thoughtlessly left on the other side of the room, away from the fireplace. The ink inside is frozen stiff. You’re not writing for a while.

Your only recourse is to set the small bottle next to the fire. Or you could rub it in your hands. Or put it in your pocket for the body heat. Whatever you do, toss a chunk of that split ash-wood into the fire and get the flames going.

And tell whoever not to move the ink bottle again from the hearth or we’ll be stuck writing with the ash end of a burnt stick.

(black ice)

* * * * * * *

A dark mood covers a swath of the colony of Massachusetts. Two towns separated by eight miles—it’s a snowy hike of two to three hours from Concord to Weston—are sites of a grinding turmoil over tea and the last-resort tea dumping of three weeks ago. The Jones family in Weston is vocal about the need for loyalty to the imperial government, its laws and officials. Reverend Isaac Jones laces his pastoring with opinions about supporting the British Crown. Pro-imperial feelings run so high in Weston that the town hasn’t organized a local Committee of Correspondence to advocate for colonial rights, a move in contrast to neighboring communities.

In Concord it’s the opposite, with a town meeting held yesterday to thrash out the response to Boston’s request “to resist in a most zealous and determined manner” the current British tea laws. Attendees in Concord went even further and considered what to do with their version of Weston’s Joneses : people who chose to drink tea as a pro-imperial political statement. After all, some Concordians concluded, they would then be regarded “as enemies to their country.”

(Concord’s Town Hall, right)

* * * * * * *

One of those colonists on Cape Cod who quietly unloaded tea from a stranded British ship is now sick. He’s got smallpox, a deadly disease. He’s in the new hospital in Marblehead devoted to caring for smallpox victims. The site is also where inoculations occur, a practice that outrages many local residents more than the controversy over tea. They’ve been protesting against the new hospital and threatening to tear it down.

But guess what—there’s a rumor in Marblehead that tea has some sort of ingredient that attracts smallpox. The reaction is what you’d expect—put two and two together and now we’ve got a tea sympathizer afflicted with smallpox in our town. And today, 250 years ago, a group of fishermen arm themselves with rocks and long wooden staffs to drive off a small boat carrying wealthy passengers said to be seeking inoculation at the new hospital. Dubbed “the Enockulation Gentry” by the fishermen, the people on the boat signal to the ship captain: heave to and find another wharf outside of Marblehead. An attack is thus avoided. The fishermen claim a bloodless victory. It’s off to Rea Tavern for a hot rum on a cold day.

(Rea Tavern)

* * * * * * *

The leader of a college is dealing with the withdrawal of a promising young student. Frustrated with the life and prospects of a college graduate, the young man had left Kings College (future Columbia University) in order to marry and start a new life with his bride. The Reverend Myles Cooper, superintendent of Kings College in New York City, has written to the ex-student’s wealthy family back in Virginia, to the step-father, actually, explaining the settling of financial accounts and to send well-wishes to young “Jacky”. Reverend Cooper hopes to see again Jacky and his step-father George Washington, though Cooper suggests it might be best to wait until the step-son had been a husband for a while. It’s the Reverend’s way of predicting that a dose of real life might alter the young man’s outlook. Maybe the Reverend is thinking the Washingtons are wealthy enough to pay for the new Custis family to relocate to New York City for the re-starting of a college education.

(Kings College)

* * * * * * *

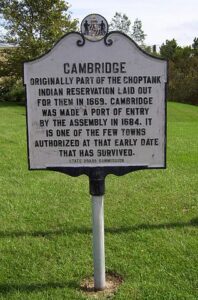

Harry has relocated to jail. He’s sitting in a cell in Cambridge, colony of Maryland, county of Dorchester on the eastern shore. Cambridge is the county seat.

Harry has been in jail for a day. He’d stolen two hats, twenty yards of white linen, and a shockingly large amount of rough cloth—forty-three yards worth—used to make clothes for enslaved people. Like Harry. Harry’s enslaver is Roger Woolford and Harry snatched the goods from a storehouse owned by a neighbor of Woolford’s, John Nixon.

That’s a lot of cloth. To what end?

Harry leans back against the wall and thinks through his next move.

White judges. Black criminal. Harsh laws.

Hold on, though. Just wait for a second. Let’s think through this. We’ve got the time. Not going anywhere.

Harry sees an idea in his head.

(also home of Harriet Tubman)

* * * * * * *

A judge in Pittsburgh is alarmed today, 250 years ago. He’s Aeneas Mackay and his jurisdiction in the town fits squarely into the government of Westmoreland County, colony of Pennsylvania. Mackay’s office derives its existence from the Pennsylvania colonial government and the colony’s charter, its founding document. Scottish by birth, Mackay is a full-fledged colonial Pennsylvanian.

What he also is at the moment is panicked to the point of freak-out.

Because of his formal position as magistrate, or judge, Mackay is a man of local power, responsibility, and authority. He’s the face of Pennsylvania in a town, Pittsburgh, that has men in it who claim to be the face of Virginia. Virginia’s government has acted to seize lands in the broader Ohio River valley, including Pittsburgh. Representatives of a rival governing unit are now on the scene, declaring their status as the new controlling entity attached to Augusta County, Virginia. Dr. John Connolly is the primary spokesman for Virginia Governor Dunmore, and Connolly has twelve armed men with him as an official military force.

Today, 250 years ago, Aeneas Mackay, the Scottish Pennsylvanian, sees nothing but trouble ahead in the disputed control over Pittsburgh.

(Pittsburgh, ground zero)

* * * * * * *

A single day. That’s the length of the entire fourth session of the colonial legislature in South Carolina. Today, 250 years ago, in Charleston. It starts in the morning and ends in the afternoon. The day-long session is the latest show of ill-will, hostility, and bone-deep disagreement among the legislators, councilors, and governor of South Carolina. On the surface, the problem is about providing public funds for the support of British radical John Wilkes, a controversial member of Parliament. Most of the Assembly—the lower house—says yes. The governor and the Council—the upper house—say no. But that’s not the crux of it.

The bitterness has boiled up from hotly disputed philosophical opposites. Many members of the Assembly base their views on the belief that the lower house controls public money as a cherished British constitutional right rooted in the Magna Carta. The governor and councilors believe no such control exists because the colony’s rights derive from the monarchy and exist at the pleasure of the monarch. Rights inherent to ourselves as Britishers versus rights inherent to the British throne. Hard to get more opposite than that.

No wonder they don’t want to be in the same place for more than a day.

(Charleston in the distance)

Also

The stage is set for a promising drama.

Chairs moved in place. People practicing in their heads what they planned to say in full voice. Other people shifting in their seats to see a little better, to hear a little more. Lighting from candles and sunlight. Heat from fireplaces and thick clothing.

And what will this performance be? Not a play of fiction, to be sure, for this was a story made in the halls of British government. A few days ago, the British imperial government’s solicitor general, Alexander Wedderburn, had confronted Benjamin Franklin in Parliament. Wedderburn had sat at the head of a committee and declared the government had a right to know how Franklin had gotten the private letters of imperial officials. Franklin’s answer: “I thought this had been a matter of politics and not of law. I have not brought any counsel.” A committee member remarked, “Dr. Franklin may have the assistance of counsel, or go on without it, as he shall choose.” Franklin chose counsel. And how much time will you need to prepare with your counsel, he was asked. “Three weeks,” came the reply from the American with the small, round glasses.

Wedderburn was known as a tough questioner and fast thinker. He was eloquent and capable of stringing facts into a comprehensible chain. He prided himself on his ability to speak, to interrogate, to impress. Oddly, these same abilities often eluded him in social settings. Aware of this habit, Wedderburn preferred a professional setting for making himself known.

Yes, the stage is set. Two weeks away.

(Alexander Wedderburn)

For You Now

We have two people waiting for an outcome. One is Benjamin Franklin, waiting for his day in front of a Parliamentary committee in London. The other is Harry, waiting for his day in front of county judges in eastern-shore Maryland. Franklin’s offense is imperially-oriented; he stole letters, or was given stolen letters, to be precise, that were injurious to a small group of colonial officials. Harry’s offense is more legally-oriented; he stole garments, belonging not only to someone else but to a group of people framed by law, and perhaps more importantly, by custom, as superior to him.

We also have people pulling on a line. That’s my phrase for the folks in Charleston, Pittsburgh, and various towns in Massachusetts who are trying to determine exactly who, what, and where are the sources of basic rights and basic powers. They’re pulling a line tied around that source, the anchor point, the immovable thing. When I think about it, though, my reference to the immovable thing at the end of the tied-off line doesn’t allow for change. It doesn’t allow for life. For living.

The better way to think of it is a word I used earlier: “root.” A root is an end, too, but it’s an end that can keep growing and going, deeper and deeper, so long as the conditions are right. The root-end an organic plant isn’t the dead-end of an immovable point. So I might better say that those folks in Charleston, Pittsburgh, and various towns in Massachusetts are actually searching for a source that gives life. Some of them believe that, above ground, conditions look threatening, dangerous, inhospitable.

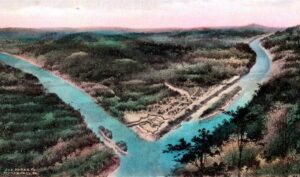

(a better image)

Check the weather. I just did. Looks like bitter cold coming soon. Frozen ground. Two and a half centuries ago it would also have meant frozen ink.

Warm the bottle.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: can you see down to the end of the root? If so, what’s the source of rights and power? If not, keep looking.

(Your River)