Americanism Redux

February 27, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1775

Sometimes life is a nesting doll.

Inside of one thing is another thing, and then another thing inside that thing. And so it goes.

Today, 250 years ago, we go inside, and again inside, and once more inside.

You’re surprised, then you’re not surprised, and then you don’t know what to feel.

* * * * * * *

(the Salem Standoff)

So, with all of the loud noises and big sounds on the surface, the bosses back home in Parliament want action? All right, fine, here’s action. Coming straight at you, action on the way. That’s the mindset of British General Thomas Gage.

A few days ago, British Redcoat General Thomas Gage was ready at last—time for action to turn this thing around, to push back against the push-back. He ordered two British officers to dress civilian-style—brown clothes and red kerchiefs—and travel out of his headquarters-town of Salem, colony of Massachusetts, and see if they could uncover information about secret supplies of weapons and ammunition stowed away by colonial-rights protesters. Their cover was blown by a black woman who served them dinner; she figured out their assignment, scoffed at them, and ridiculed the mission. Three days later, the two British officers returned to Gage after struggling to complete their assignment.

Gage wasn’t finished. Armed with half-useful information, he ordered Lt. Col. Alexander Leslie to take 240 Redcoats from the 64th Infantry Regiment and search for weapons and ammunition on the outskirts of Salem while residents were attending church services. Word quickly spread of Leslie’s expedition. Hundreds of local people turned out with muskets, swords, and hatchets. A tense standoff ensued at North Bridge. Nerves at the breaking point. Sweat-soaked shirts. Jittery hands holding guns and knives. Someone thought of a bargain—allow the Redcoats to cross the bridge, spend minimal time in their search, and then return to Gage’s headquarters by how they came. It worked. No violence, though every second and minute screamed of the possibility of bloodshed, battle, war.

“It is regretted that an officer of Colonel Leslie’s acknowledged worth,” observed a Redcoat officer, “should be obliged in obedience to his orders, to come upon so pitiful an errand.”

* * * * * * *

(Derby’s home in Salem)

Richard Derby, Sr is one of the local residents who stood at the North Bridge during the standoff. He had built and owns the largest wharf in Salem and also operates a successful shipping company—until the British shut down the ports, that is.

He knew that the weapons the Redcoats wanted most to seize were eight cannon that colonial rights supporters had collected. He also knew that with the Redcoats’ mission discovered, he and his neighbors could delay Leslie’s soldiers at the bridge until the cannon had been hidden. When Leslie yelled for the protesters, the resisters, the…rebels, to stand aside, Derby shouted back, “Find them if you can! Take them if you can! They will never be surrendered!”

Derby, the Derby family, and the hundreds of neighbors and townspeople who had turned out at the sound of alarm watched as the Redcoats abandoned their mission and went back to Salem. Everyone—Redcoated, brown-coated, and no-coated—realized that something life-changing had been averted.

Inside a trans-Atlantic dispute over imperial authority and colonial rights, the fact of a planned action fades away. The result of war’s absence continues, and the world keeps turning.

* * * * * * *

(Hamilton, a few years later)

He’s all passion, energy, and forcefulness. That’s the clearest takeaway from Alexander Hamilton’s second published essay, a lengthy piece entitled “A Farmer Refuted”. It’s an exhaustive chastisement of Samuel Seabury and his pro-imperial “Westchester Farmer” released earlier this year. In page after page Hamilton assembles ancient history, recent history, colonial sources, English sources, philosophy, theology, economy, and anything else he can think of to dismantle Seabury’s criticism of the Philadelphia Congress last fall.

Hamilton concludes, “I verily believe also, that the best way to secure a permanent and happy union, between Great-Britain and the colonies, is to permit the latter to be as free, as they desire.”

In his next essay, Hamilton pledges, he will turn to the present crisis of the dumped tea and Coercive Acts. Get ready for another forty-page stampede as the young author slashes at his adversary nearby, perhaps also at some opponents further away, and possibly a few deep inside.

* * * * * * *

(a Committee of Correspondence meeting)

There’s a boycott inside a boycott.

Eight towns in eastern Massachusetts have convened their respective “Committees of Correspondence” to design a second boycott. In addition to the general economic boycott of British goods—a colonial rights Congress’s protest measure against the Coercive Acts, which were a retaliation for the anti-tea protests—the eight Committees of Correspondence are now organizing a companion boycott. No one in the eight towns will be allowed to assist the British Redcoats currently stationed in Boston and Salem. No wagons for food or wood, no tools, no bricks, no tent poles, nothing. It’s a boycott against helping the Redcoats.

A community boycott inside of a continental boycott.

* * * * * * *

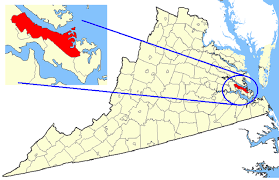

(Digges’s county of York)

47-year old Dudley Digges tells his wife Elizabeth that, yes, they voted me in. A county meeting in York County, colony of Virginia, has chosen Digges to be one of its representatives at the colony’s convention to be held in Richmond three weeks from today. Twenty-days of future.

Digges’s election is one of hundreds occurring up and down the Atlantic Coast in these winter weeks. People are coming together within colonies to select representatives to do each colony’s business in the uncertain days ahead. Winners like Digges will then include in their work the selection of a smaller number of representatives for the planned second Congress in Philadelphia during May. It’s a process unfolding from larger to smaller as numbers but going from smaller to larger as span.

Digges has won votes before for local political offices and for militia colonel. But nothing has been quite as ominous as this election outcome, and it’s the twenty-one days ahead that make it so. Inside the present is a near-term future filled with risk, danger, and consequence.

Digges knows how to localize, how to understand and decide on local issues and choices. But that verb—to localize—takes on a weight and a burden he’s not had to carry before. Is local the same when he’s demanded to look at it regionally, continentally, globally? That’s a different local.

Inside the local in such a moment is a broader reality than he’s ever had to fathom.

The twenty-one days may tell the tale.

* * * * * * *

(a winter trail in the Ohio Valley)

William Skilling signs the contract. His name, in ink, on the parchment, beneath descriptions of all the things he’s obligated to do. Hesitations or not, it’s done now.

The core of these obligations is to lead a group of servants and enslaved people west to the Ohio River in the vicinity of its confluence with the Great Kanawha River. He will behave quietly, act soberly, and “set a good example” to those whom he leads westward.

This group people will have varying degrees of unfreedom. Some will have freedom after a period of time, some never. As a confined and bounded group of the laboring unfree, they are among the first formally brought from the Atlantic Coast hundreds of miles inland.

Skilling will take them to a place where, for the first time, they will see waters flowing west, away from a world that denies much to them and despises much in them.

The man to whom Skilling is obligated under contract is George Washington, who expects his servants and enslaved laborers will arrive as they departed, his property, on his property, next to the westerly flowing waters.

* * * * * * *

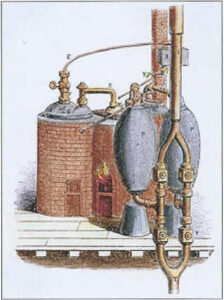

(early steam engine)

Water sizzles and hisses against the metal in the white-hot furnace. The workmen pull the freshly-cast cylinder from the scorching heat, all under the watchful eye of furnace owner Peter Curtenius. They transport the cylinder to the new steam engine, a machine designed by Christopher Colles to operate the waterworks of New York City. They insert the cylinder into the apparatus and then stand back. A small group studies the engine, a technology unlike any seen before.

“This is the first performance of the kind ever attempted in America”, a newspaper reported, “and allowed by judges to be extremely well executed.”

Nestled in a city of horse-drawn wagons and wind-powered ships, innovation in the power of steam is another day deeper, another day closer, to a revolution of life.

Also

The snow melts in Selborne of the English countryside. The ground is wet, soft, and cold. Up through the soil comes the crocuses, the first flowers of winter’s final calendar month.

Yellow, white, and purple, the crocuses catch the gaze of Gilbert White, who writes a line in his journal.

The flowers have blooms the shape of stars.

* * * * * * *

(in London)

Sixty miles away is Benjamin Franklin, in London. He’s writing, too, but in letters, not a journal. Like Gilbert White, Franklin observes and it’s his observations that he’s sharing with two people he knows well.

One is James Bowdoin, of Franklin’s birth town of Boston. Franklin states that unity of the colonies is the key, the predominant fact that can override everything else. In the current instance, Franklin adds, the boycott depends above all on the unity of the colonies.

The other is to Joseph Galloway, of Franklin’s adopted home town of Philadelphia. Franklin warns that Galloway’s emphasis on maintaining the union between Britain and the colonies is so well-known that he’s verging on becoming seen as an apologist for British imperial authority. And if such a union can be continued, Franklin adds, it would be a worse outcome if major changes aren’t made.

Inside the current resistance is our potential solution, and inside the status quo is our potential destruction.

For You Now

Think of those nesting dolls.

It’s all so cute, as the small becomes tiny and the tiny becomes teensy.

But what if the smaller becomes more explosive, more significant, more revealing?

The attempted Redcoat mission at Salem is a microcosm of what many imperial officials in Parliament believe should be happening. In the singular and the miniature, this is precisely the remedy they’ve been demanding. Organize a military mission and send it out to seize and strike.

Yet the actual outcome is shocking, unexpected. The macro went micro and the result was zero. Now what?

It’s easy to forget that going from larger to smaller was part of the process in the Manhattan Project. Going down to the atomic level produced chain reactions and an atomic bomb.

The choice will be to continue following the path that has begun, with tweaking and tinkering, or whether to pull back completely and rethink which path is best. And while all this choosing is going on, cracks and breaks are widening to the point of unrepair. A new form—like the cylinder—may be going into the fire.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider this: as you see our American life unfolding, do you see an important meaning in a smaller moment?

(Your River)