Americanism Redux

December 14, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

The front. That’s where you’re looking from—the front of the room, the front of the group, the front of the line, the front of the moment.

The front is a perspective all its own.

* * * * * * *

Today, 250 years ago, the smell of tea is still in the nostrils of Reverend Jonas Clarke of Lexington, Massachusetts. Two days before, he’d stood close to the pile of tea gathered by outraged residents of Lexington, brought to the center of town, and ignited in a smelly, smoldering heap. The wooden boxes and cloth scraps had started burning as the smoky lump on the ground finally caught flame. People had yelled their approval of Reverend Clarke’s words of fire: “Should the State of Our Affairs require it, We shall be ready to sacrifice our Estates, and everything dear in Life, and Yea Life itself, in support of the common Cause!!” From the front of the group and closest to the burning tea, Clarke had seen the faces of his congregation illuminated by the flames.

The ashes and scorched ground are two-days old in Lexington, the second public action against tea in as many weeks, 250 years ago today.

* * * * * * *

He’d never stood at the front of such a mass of people, and that’s saying something.

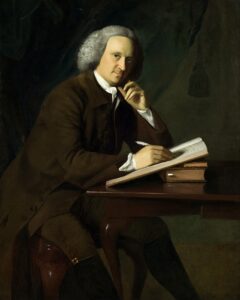

Today, 250 years ago, Samuel Phillips Savage of Weston, near Boston, is 53 years-old, a shipowner, a town office-holder, and a merchant who serves as wholesaler to smaller shops and stores. Savage has crafted business deals, arranged trade strategies for customers, and kept strict watch over local and regional purchasing trends. More than money is in this man—he reflects on religious faith with deep fervor, experiments with agriculture, tracks star movements in the night sky, and reads avidly for self-enrichment. He’s also a strong supporter of the colonial rights cause, on par with Reverend Clarke and close friend of Samuel Adams’s. He’s feeling at odds with his brother Arthur who is showing equally strong connections to England, the British empire, and the vast streams of British culture and way of life. They’re heading on a collision course with wreckage ahead.

Savage has been chosen moderator for today’s meeting at the Old South Meeting House in Boston. It’s the topic you’d expect—tea on the three British ships anchored in Boston harbor. Once again, 5000 people, almost one-third of the town’s population, have crammed into, around, and near the building. The position of meeting moderator in these recent events seems to shift from person to person; Savage is the latest to accept the duty of standing at the front.

Here’s what he sees. Talking. Staring. Whispering. Hand-raising. Back-slapping. Hand-holding. Heads nodding. Heads shaking. Arms extending. People rising up, re-seating, re-shifting in their seats. Clear sounds. Muffled noise. Body heat. A sense of togetherness and power in the air. Savage seeks to keep order, maintain calm within the crowd as best he can, include those who want to speak, and point the event toward a decision.

It’s a galloping horse and Savage hangs on for dear life as the meeting careens forward to a result: the owners of the ships will go to the customs house to seek official clearance for the vessels to weigh anchor, leave Boston harbor, and, presumably, begin the return voyage to England, carrying the tea.

People flow out from the Old South Meeting House. Some of them turn and see Savage still at the front of the emptying space.

(Samuel Phillips Savage)

* * * * * * *

The British royal governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson, scoffs at this latest event at Old South Meeting House. Hutchinson writes to his brother that “I hardly think they will attempt sending the tea back, but am more sure it will not go many leagues [in distance]; it seems probable they will wait to hear from the southward, and much will depend on what is done there.” By “southward” Hutchinson means Philadelphia and New York City.

As a leader, Hutchinson likes to know what others do elsewhere and then insert that fact into his final calculations. When he’s standing in front, he doesn’t want to lose his balance.

(Thomas Hutchinson, 32 years before the weight of the world was on him)

* * * * * * *

John Adams writes to Catherine Macaulay in London, England: “The last ministerial Maneuver, has excited a more and determined Resistance than ever has been made before – the Tea Ships are all to return, whatever may be the Consequence. I Suppose your wise Ministers will put the Nation [England] to the Defense of a few Millions to quell this Spirit by another Fleet and Army – The Nation is so independent, so clear of Debt, and so rich in Funds and Resources, as yet untried, that there is no doubt to be made, She can well afford it.”

“But let me tell those wise Ministers, I would not advise them to try many more such Experiments. A few more such Experiments will throw the most of the Trade of the Colonies, into the Hands of the Dutch, or will erect an independent Empire in America, perhaps both. Nothing but equal Liberty and kind Treatment can Secure the attachment of the Colonies to Britain. We are much-concerned here at the unhappy Divisions among the Friends of the Constitution in the City of London. We hope to see a Reconciliation, as much depends on their Union, and Exertions.”

Standing at the front of now and looking to the future, Adams warns about wrong moves in response to the formal return of the ships, an action he’s sure will happen soon.

(John Adams, after fame found him)

* * * * * * *

The printer of the Connecticut Courant inserts into this week’s edition of the newspaper a quote from an unnamed “gentleman” in London. Two months ago the anonymous source is said to have told Lord North, the British prime minister, that “a storm is now gathering in America, which will either ruin the friends and dependents of my Earl of Bute [a close confidante of George III], or separate the colonies forever from its dominions.” That’s a jolting choice: either the British monarch ejects his friends from power or the British colonists cut the cord with the mother country. The words spoken among the golden leaves of October look all the more stark when read beneath the bare trees of December.

So it’s not really a surprise when you turn the page of the same Connecticut newspaper and the printer has inserted a special announcement for the reading (and listening) audience. The printer asks local residents if the time had arrived for them to congregate in an appropriate place to consider “measures similar to those of our Sister Colonies respecting the baneful Article of Tea.”

In so many words the printer asks for someone to step to the front.

(Hannah Bunce Watson, co-publisher of the Connecticut Courant)

* * * * * * *

Some “Sister Colonies” contended with other issues.

North Carolina’s colonial government, located in New Bern and consisting of the royal governor, the legislature, and the upper council, worked to finish a proposed law to “prevent the willful and malicious killing of slaves.” First-time enslaver-offenders who violated the law would be fined L100 and sentenced to six months in jail, while second-time enslaver-offenders would be put to death “without clergy”; in other words, two strikes, you’re dead. Lawmakers made certain that a waiver existed—enslaved people could be killed after they had either actively resisted their enslaver or retaliated against “moderate correction”—no punishment for these violations would be permitted against white murderers.

Will the relative unity in North Carolina’s government with this heinous topic carry over to the issue of tea?

For the time being, they’re standing together at the front of an issue that is nothing but bottom, underside, and pit-level.

(Governor’s house, New Bern, North Carolina)

* * * * * * *

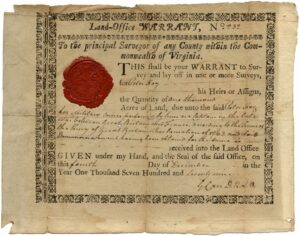

Today, 250 years ago, Peter Hog is on his way home. It’s been eleven weeks since he’d seen his family in Virginia. He’s canoeing on the Ohio River, taking him to the Great Kanawa River, and from there to a final exhausting trek across rugged terrain toward Augusta County, Virginia. He thinks he’s got it done—that his 2000 acres of land owed him for service in the French and Indian War are secured at last with title, deed, surveyed lines, and whatever else amounts to verification of British-colonial land ownership. He’s worried about not knowing how the local government will work; will Virginia’s Governor Lord Dunmore will have authority there or will some model like the West Florida colony be used? Hog doesn’t know. At this point, paddling in the vast river, he’s thinking far more of his family than he is of powder-wigged politicians.

From the front of the canoe, Hog leans cautiously forward to detect a landing place on the river bank.

(the piece of paper sought by Peter Hog)

* * * * * * *

Hog’s best access to political power and influence is his relationship with George Washington. They know each other from serving in the French and Indian War. They also agree on the potential prosperity residing in millions of acres of land in the Ohio River valley. Today, 250 years ago, Washington writes instructions on transporting a barrel of white thornberries to Virginia’s royal Governor Dunmore. A thoughtful gesture to make the decision-maker feel better, the herb helps treat diarrhea.

It’s consumed as a tea.

An act of kindness is a quiet step toward the front.

(pre-tea thornberries)

* * * * * * *

Further west of the Ohio River valley, a supposed visitor to “the interior of North America” asserts a shocking discovery has been made. “A nation of Jews” are living “among the Indians, (and) who call themselves the tribe of Naphtali.” They worship as Jews do in Europe. The visitor has no explanation for how they arrived west of the Ohio.

The front of reality is still reality. Beyond it lies gray and fading lines of bluffs, guesses, and projections.

(the real Naphtali, son of Jacob)

* * * * * * *

In Wilmington, colony of Delaware, the Reverend Lawrence Girelius stands in front of his congregation at Holy Trinity Church, also called the Old Swedes Church. He knows the day down to a degree—that is, to the extent it feels cool or chilly or bone-deep cold outside. As he looks out at the congregation in the pews, he’ll make the judgment of the three degrees silently, to himself. If he gets to bone-deep cold, or even close to it, he’ll know what to do.

He’ll switch to Swedish in his words to the people gathered there. When it gets truly cold, the number of older Swedish immigrants in his church will increase significantly. The cold drives the Swedes inside the church. The Reverend will speak in Swedish on those cold days.

Reverend Girelius stands there today, 250 years ago, with two young people in front of him. Each of them is 22-years old. He says, in so many words of English, will you, Jacob? And will you, Rachel? They both say an eager “yes” and now they’re the Brooms, husband and wife. No one in the church knows that fourteen years from now Jacob Broom will be a Delaware signer of the American Constitution.

In change there is a front, called the edge by some, which, over time, becomes a center of continuity.

(the space where Reverend Girelius spoke his native language to cold, old Swedes)

Also

Today, 250 years ago, hundreds of scholars sit at desks, bent over paper of parchments. They read and scribble, read and scribble. Their hands stiffen, their backs ache. More than four thousands books are stacked around them. They copy and copy and copy in the city of Beijing.

Their project is at the order of the ruling Qianlong emperor of China’s Qing Dynasty, the ruling class in power for nearly 150 years. The work is Siku Quanshu, or the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries. Today’s task is this year’s task, the opening portion entitled the Annotated Bibliography.

The books have been brought from private owners across the Chinese empire. They represent every book owned and possessed in the country. The goal—the command—is to collect all written knowledge and all knowledge of writings. The scholars re-write the words for inclusion in a massive encyclopedia. Some of the books will be regarded as anti-Qing, however, and thus will be burned in imperial fires.

In China the flames turn to ash books of opposition that could have been written in America. In America the flames turn to ash boxes of tea first grown in China.

Smoke rises from fires on different sides of the earth.

For You Now

They’re doing two things in Boston.

First, after Lexington’s tea burning, now the second display of forceful action against the East India Company’s product, the anti-tea protesters are dealing with regulations. That’s the reality of the meeting moderated by Samuel Phillips Savage—deciding to comply with rules requiring official approval before ships carrying taxed goods can leave port. They’re obeying the procedures, which also include paying for unpaid tea taxes on the 20th day if still unloaded after docking. That 20th day is December 17. Day 20 is a ticking clock.

Second, and this is in tension with compliance and rule-following, they’re seeking a form of protest that is effective without being reckless, productive without being dangerous. The ships aren’t blown up, the people aboard them aren’t killed, either of which might have happened. Instead, the path chosen in Old South Meeting House suggests a formal returning of the ships and their tea back to England before the ticking clock of Day 20 stops.

But do Lexington’s actual fires and Boston’s potential returnings amount to the same thing? Do the events where Reverend Jonas Clarke and Samuel William Savage stand at their respective fronts form a common ground?

John Adams is certain they do. Thomas Hutchinson isn’t so sure.

(interior, Old South Meeting House, where the eagle watches the front)

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: which ground is firmer today?–that under the feet of those confident in the American future or those lacking confidence in the American future?

(a river before the rapids)