Americanism Redux

August 22, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

(the blues say “end”)

What if this really is the end?

…of…

It. That. Them. Us. Your call as to the object of the question.

It does happen, you know, an end, the end. And then there is a next, which can only start if…

…this really is ending.

Today, 250 years ago.

* * * * * * *

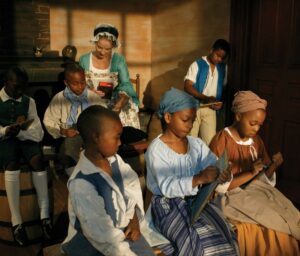

(Ann depicted)

The black children look sad. Standing outside the school in Williamsburg, colony of Virginia, they aren’t sure what will happen to them.

Their teacher is dead, the life of 58-year old Ann Wager ended a couple of days ago. She was the only remaining teacher at the Bray School that had been operating for the past fourteen years. Ann had taught reading, writing, a few work skills, and the basics of Christianity to a group of free and enslaved black children. Almost four hundred students had come through this school.

The end of Ann Wager’s life means the end of Bray School’s purpose, which means the end of education for these black children of Williamsburg, while many Virginians are seeking to end the problems afflicting colonial-British relations.

End to end.

* * * * * * *

(Adamses depicted)

It seemed like the end at the farm. Days upon days of intense heat and the burning sun. Crops and grass and trees drying up. The ground so hard that you felt it in your feet through your shoes. It’s the end of life in a scorching summer.

Then, the wonderful feeling unfolds when the rain begins to fall. It was almost biblical, hour after hour. Twelve inches in total. A God-send in the opinion of Abigail Adams as she looks after her and husband John’s four children while John travels toward Philadelphia for the special “congress” there.

Abigail misses him terribly. The days apart like a month. She’s seeking comfort in the teachings of Polybius, which both she and John admire; a peace made through the surrender of liberty is shameful. She’s also reading the multi-volume series, “Ancient History”, written by Charles Rollin. She has asked their young child Johnny to read it aloud to her. In the shared experience of the spoken book Abigail hopes her son finds a love of history and that she finds calmness and endurance. The truth is that Abigail doesn’t know if she’ll see her husband alive again on the Adams farm in Braintree, colony of Massachusetts. If this is the end of their marriage on the rain-soaked ground.

* * * * * * *

(Josiah depicted)

Josiah Quincy sees the end of his days in Boston.

Quincy has paid for a berth aboard the “Katy”, Captain John Davis’s vessel sailing any day now for London. Quincy has accepted the advice and urgings of his friends, who have begged him to go to England for the winter. They believe he can help persuade enough members of Parliament and the imperial court of King George III to reform the harsh laws passed to punish Boston and Massachusetts for the tea protests last December. Maybe he’ll meet Lord Rokeby, whose popular pro-colonial book has just had its fourth printing and, the advertisements say in Boston, has succeeded “in removing the prejudice and concerning the people of England.”

Quincy relented, bought a ticket from Captain Davis, stowed his luggage on the Katy, and makes a mental list of people like Rokeby whom he should meet.

Meanwhile, he finishes writing a goodbye letter to a colleague in Philadelphia who will be attending the special “congress”. He politely dismantles the idea that a colony like Massachusetts should soften and pull back from an aggressive resistance to British authority. Quincy’s response: “Those maxims of discipline are not universally known in this early period of Continental warfare; and are with great difficulty practiced by a people under the scourge of public Oppression”.

Hmmm: “this early period of Continental warfare”. Explosive words. Sounds like the sighting of an end by the man bound for London.

The Katy awaits the bracing spray of the North Atlantic.

* * * * * * *

In Salem, the only officially open North Atlantic port in Massachusetts, British General Thomas Gage rubs his forehead, rubs his eyes, rubs his temples. He’s got a tidal wave of a headache in serving as military governor of the colony, appointed by the British imperial government. Maybe he’s dreaming of his worst enemy and envisioning the guy sitting in Gage’s chair.

But with eyes open and reality-light streaming in, it’s the nightmare that continues.

The source of Gage’s headache is a list a mile-long, today, 250 years ago. Want to see it? Here goes.

He can’t get enough wood and food for his Redcoats encamped on Boston Common because the people of the town hate them so much. He’s dealing with rumors that he’s sending a regiment of soldiers to Worcester to force the judicial courts to open and operate as usual; the option had actually crossed his mind. He’s coping with reports that British infantry are deserting in one’s and two’s; the punishment for desertion has had to be intensified. He’s struggling to shore up soldiers’ morale; townspeople are taunting them about decapitation with field scythes. He’s reacting to announcements of donated goods arriving in Boston from colonies as far away as North Carolina and Georgia. He’s busy writing a proclamation that will ban a town meeting planned for four days from today to start a process of creating a new kind of legislative body for Massachusetts, circumventing the existing structure he’s trying to re-create. This seasoned, decorated, and battle-tested British general is literally chasing down posted sheets of paper that have details of the town meeting he’s desperate to ban. Good God, what’s next?

The end Gage is beginning to see is of a career, or a command, or a community where he’s posted, and none of them come with good tidings.

In the distance, toward England, a ship grows smaller on the horizon.

* * * * * * *

(an older William Tudor)

If William Tudor and Thomas Gage knew each other well, their hatred would be mutual.

Tudor is 24-years old, a graduate of Harvard, a mentee of John Adams, and already one of the best attorneys in Boston. He’s full-on patriot, a supporter and advocate of colonial rights in every form and function. He’s part of the group watching Gage and his Redcoats like the hawks eyeing baby sparrows in a twig nest. He knows all the factual accounts, all the rumored accounts, all the in-between accounts of goings-on with British military units at Boston Common and Gage’s headquarters in Salem. He’s skeptical in accepting at face value, analytical in observing day-to-day, and reliable in sharing every ounce and iota that saps the power and strength of the military force imposed on his hometown.

Tudor knows the residents of Boston are grappling with British punishment, people like David Jeffries who is funneling donated goods from colonies as far away as the Carolinas and Georgia. Jeffries couples his donation work with a spiritual faith in God’s wisdom and protection. Tudor judges that local folks have also planted their faith in the “congress” that will meet in Philadelphia. He hopes the congress will “at least cement the Union of the Colonies.” That’s the minimum, the base line.

If that’s not achieved, not reached, Tudor sees an end in sight.

* * * * * * *

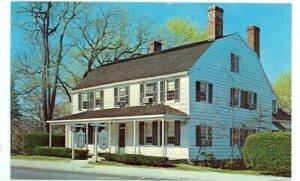

(Square House)

Dr. Ebenezer Haviland is in Rye, Westchester County, colony of New York. He and four other people are scrambling to arrange a meeting in White Plains at a tavern he owns, the Square House, one of the most popular gathering places in this region. It’s always clean, always committed to customer service. That’s exactly the atmosphere Dr. Haviland wants for his four companions as they sort out delegates to send to Philadelphia for the “congress” of such importance.

Whatever happens in Philadelphia, these unknown delegates can return to Square House, savor a meal, sip an ale, and tell their stories to the innkeeper and surgeon, Ebenezer Haviland. For a moment, that will be their end.

* * * * * * *

(up from North Carolina)

Contrasting winds blow up the coast from North Carolina. Yes, some donated goods made their way to Newport in the colony of Rhode Island and finally to David Jeffries in Boston. They arrived in the spirit of people who’d gathered in North Carolina’s Chowan County. There, in a meeting, they had approved eight resolves orbiting around a central theme: the harsh British laws in Massachusetts “are a dreadful message of what we have to apprehend from a (parliamentary) Legislature which claims the power of making Statutes to bind the Inhabitants of the Colonies in all cases whatsoever.” None of the resolves, it should be noted, referred to any aspect of enslavement.

At the same time, townspeople of Halifax, North Carolina, almost doubled Chowan in the number of resolves, enacting fifteen of them. In milder and mellower tone, they pledge loyalty to the king and to their determination to continue paying their debts to British creditors. They will keep their courts and legal system in daily operation. The principles guiding their reaction to British policy will be justice, honor, gratitude, and self-interest. Enslavement interests them so much they don’t mention it. It’s apart from their reaction.

They want an end so they can continue.

* * * * * * *

(a co-author, Anthony Benezet)

A new book is on the streets of Philadelphia today, 250 years ago. Two men are co-authors of one book on two threats. Anthony Benezet, Quaker, and John Wesley, Methodist, have teamed up for “The Potent Enemies of America Laid Open: Being Some Account of the Baneful Effects Attending the Use of Distilled Liquors, and the Slavery of the Negroes.” It’s available for purchase in the place where delegates of the highly anticipated “congress” will gather.

Unwritten subtext: it’s the internal stuff that will end you.

* * * * * * *

(back to the problem source)

It was internal stuff, or stuff taken internally, that got this crisis going in the first place. Tea. Believe it or not, nine chests of tea have been carried by a small ship, the “Mary and Jane”, to the Maryland-Virginia coast. A few men had agreed to be consignees for re-sale of the tea until the chests were stopped by local colonists. Paul Loyall of Norfolk, colony of Virginia, has called together a meeting of a colonial protest committee to decide what to do with the tea. They vote to “send it back” and to inform the consignees of their decision. No further trouble from the landed tea ensues on this day, 250 years ago.

Strange end—isn’t it?—with so little fuss, surrounded by December’s hurricane of subsequent and consequent reactions, counter-reactions, and a “congress” expected to take the key next step.

* * * * * * *

(the goal in mind)

Along the Youghiogheny River, Gilbert Simpson thinks of his son. The boy is traveling in the woods at his father’s…request. Order, instead? Hard to say. Regardless, Gilbert knows his boy and the two guards he’s sent with him are hiking toward the Potomac River. Gilbert needs money to finish the project he’s been tasked to do.

He’s building a grist mill on the river. He hopes to be finished by December, a year after all the tea problems boiled over. He’s long way from them but still drowning in problems of a different kind. The war raging between Virginia’s forces and Native tribes in the Ohio River valley have caused the prices and availability of iron to skyrocket on one hand and disappear on the other, a classic case of supply and demand. Gilbert needs iron to finish the mill and he needs money to pay for the iron. So, his son is east-bound, sneak-hiking through the ravines, creeks, and hills to avoid violence, get the cash, and return to his father on the river.

One wrong step and it’s the end in the forest.

* * * * * * *

There is an end. A stopping. No more of it or this or that. A planned end feels one way. An unexpected end feels another. It can be out there or right here. End.

And often the proof is that a beginning occurs, making the end clearer as the distance grows.

Also

(man on the run)

Yemelyan Pugachev is on the run, today 250 years ago. He hasn’t counted the dead and the wounded but if he had, he would find that eight of every ten men who were with him at the start of today’s battle are now either wounded or lifeless. And there were 10,000 of them at dawn and only 2000 left as the smoke of war drifted through the night along Volga River, at Tsaritsyn, later called Stalingrad.

He and they were twice the number of the Russian Imperial Army sent to put down his rebellion. And yet, Pugachev’s forces were smashed to pieces. The cause dies while he flees for his life, 1700 miles away from Catherine the Great, the Russian empress in St. Petersburg.

It is the end.

For You Now

We’ve got ends galore in today’s Redux. They’re everywhere.

No one 250 years ago knows the end, though the feeling of ending pervades so many things. The end looms across Massachusetts, be it the end of an assignment or a potential solution. A life might end, too, as could a chance to return home. People are looking for the resource that protects them from the end. It might be in God’s heaven or it might be in Philadelphia, the town plotted as a heavenly experiment. For the wife of a delegate traveling to Philadelphia, the resource is in having a son read to her about the past.

A couple of snippets of writing have settled into me from today’s Redux. One is the remark of William Tudor, the young, brilliant lawyer. He said that basic success in the “congress” depended on deepening the union among the various colonies. I find that important in light of the latest resolves coming out of North Carolina, especially the absence of enslavement in the pronouncements. Unity of a pre-nation.

I’m also thinking about the link between Pugachev’s fate along the Volga River and Quincy’s comment along the Mystic River. The rebels in Russia have been chopped up into little pieces while a Boston colonist invokes the “early period of Continental warfare”. Such a striking contrast and reality as you consider Gage’s setting.

The end comes after a string of before and prior and previous. The end is a secondary state. The end is one way in which future becomes present.

And accordingly, the end isn’t here yet.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: when have you wrongly predicted or wrongly expected an end?

(which ends?)