Americanism Redux

August 1, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

No longer. I’m done. I’ve been driven to the breaking point, I’m breaking at the breaking point, I’m going past into whatever is next after breaking at the breaking point.

Maybe you’ve been here, with addiction, the wrong crowd, a bad relationship, a hated job, a dead-end town.

This is where a lot of people are today, 250 years ago, somewhere in this cycle.

Listen closely and you’ll pick up a phrase among some of them…

…the state of nature. Or as it’s sometimes called, the state of Nature.

* * * * * * *

(Dartmouth, Massachusetts)

We’re “afloat in a state of nature”…”if there is any Force” in Parliament’s new laws.

That’s the conclusion of approximately a hundred people from Dartmouth, a coastal town in the colony of Massachusetts. Seventy-two hours ago they met and voted to form a Committee of Correspondence. In the letter to Samuel Adams informing him of their vote, the group included the statement about the state of nature. Bad laws without consent are bad enough; if they also have armed power to enforce them, it’s the worst yet. The Dartmouth group asserted that a state of nature gives them “a fair Opportunity of Choosing what form of Government we think proper” and that they in doing so they can “Contract with any Nation we please for a King to Rule over us.” Finally, the Dartmouth group recognizes their need for “a New Charter for ourselves.”

Into, and out of, a state of nature.

* * * * * * *

(leave it behind?)

Can’t get there fast enough, thinks Cornelius, can’t get to there fast enough to suit me and my wife. Pay no attention to us on our way to the state of nature.

Around the same time as the Dartmouth group agreed that British military power behind the Coercive Acts would place them in a state of nature, an enslaved black man and his wife in Williamsburg, colony of Virginia had escaped and were heading west toward the mountains of the Virginia backcountry. They want freedom in a place as far away as possible from the chains and strictures of enslavement. The state of nature.

Cornelious has light-colored skin, as does his wife. It’s so light, in fact, that they had good luck in pretending to be free workers. Cornelius has combined his skin tone with a vocabulary and confidence most white people wouldn’t think could belong to the enslaved. They’ve used every advantage they could find in getting money together for a revolutionary sprint to the frontier.

Cornelius has to decide if he’s taking one of his most-prized possessions with them. He owns a Russian military coat, blood-red in color and thick as sheep’s wool. It may draw attention to them, so perhaps it’s best to lay it aside. Then again, if found, would the coat be a clue to pursuers?

Even ordinary items are important along the path to a state of nature.

* * * * * * *

(on Christiana’s menu today)

Today, 250 years ago, 51-year old Christiana Campbell sees a rush of customers. She’s in her self-named, self-owned tavern on Waller Street in Williamsburg, in Cornelius’s colony of Virginia. Into the tavern walks a tall man Christiana recognizes. He sits down at a table in Campbell’s Tavern, ready to dine, hungry for dinner, the mid-day meal. George Washington wants to eat before starting work later in the afternoon, the opening meeting of an illegal gathering.

Washington and 115 other men are here in Williamsburg for an historic event. They are meeting in violation of Governor Dunmore’s preferences. They were chosen through elections in fifty-six counties and four boroughs.

Three months ago the British imperial governor Lord Dunmore had thrown the Assembly out—scolded them, dismissed them, ordered them home. Assembly members met privately after disbandment and decided to reconvene on August 1 to consider a governor-less strategy for reacting to the Coercive Acts. It is now August 1, time to reconvene for Washington and the other 115 Virginians.

The timeline and calendar give this meeting a unique power. The Virginia Assembly’s actions in late May had transformed the Massachusetts-centered issue into a colonies-wide cause. And now, August 1’s place on the calendar serves as a transition between mid-summer and pre-autumn, making this Williamsburg meeting all the more influential in front of the yet-to-be chosen date for the loosely understood “congress” in Philadelphia. If airplanes had existed, the Williamsburg meeting would be building the runway for the Philadelphia take-off.

Christiana Campbell watches as the customers leave her tavern, one by one.

* * * * * * *

(his design)

Thomas Jefferson so wanted to be with Washington at Williamsburg. Sickness stopped him. Undeterred, the ailing Jefferson had reached for quill pen and paper and sat down at his self-designed portable writing desk, suitable for using in bed. He unrolled a new essay for the Williamsburg attendees. Entitled “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” Jefferson means to guide, inform, and instruct the people, ideas, and decisions at Williamsburg in his absence.

In the essay he explains the route of the colonists to their present plight. They’ve been driven there by willful actions of the imperial government, curtailing colonial rights and freedoms at every opportunity. “From the nature of things,” Jefferson wrote, “every society at all times possess within itself the sovereign powers of legislation. The feelings of human nature revolt against the supposition of a state so situated as that it many not in any emergency provide against dangers which perhaps threaten immediate ruin.”

The audience in Williamsburg who reads Jefferson’s pages stands on the fringe between manicured lawn and wild forest, peering into the state of nature, the laws of nature, human nature.

Today, 250 years ago, Jefferson sleeps in his bed and recovers from illness. His essay is already in the hands of some delegates in Williamsburg. Washington exits Campbell’s Tavern and walks to the location of the convention, at Raleigh Tavern on Duke of Gloucester Street. He hears loud voices of greeting as 116 delegates take their seats for the first session.

* * * * * * *

(Tondee’s, a quieter time)

Evidently, taverns are the place to be.

A few days earlier, a liberty pole had been dug into the dirt outside Tondee’s Tavern in Savannah, colony of Georgia. Archibald Bulloch and approximately a hundred people walked by the pole as they entered Tondee’s. Most of them were from Christ Church Parish or St. John’s Parish. Inside, they examined “the critical situation” in imperial-colonial relations. They heard read aloud letters and resolutions written in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. For many of the listeners, it was the first time they could really concentrate on the current situation. Up to now, a war had distracted them, with Natives, colonists, and British soldiers fighting over land a few hundred miles inland from Tondee’s.

The meeting at Tondee’s ended with two outcomes. First, attendees want to hear the views of people from more parishes. Second, donations will be collected and sent north to help Bostonians, epicenter of effects from the Coercive Acts.

The fighting between the colony and Native tribes had produced a temporary state of nature in the southern hill country. No one had been secure. Life itself hung on hooks and hung by threads. Thankfully, those days seemed over and the state of nature disappeared. The Tondee meeting pointed to another direction, another source of trouble that could re-hang life.

* * * * * * *

(Henderson)

In a perfect world, the Tondee group might have saved some time if they’d read Henderson’s letter. It’s not a perfect world and the Henderson letter was on its way from Maryland to Scotland.

Richard Henderson wrote two days ago in Bladensburgh, colony of Maryland to a Scottish friend. Henderson summed up the current situation with a clarity and focus rivaled by few.

Henderson wrote to Cunningham Cotbett that in his opinion the supporters of colonial right from New Hampshire to South Carolina were of one mind—that the Coercive Acts were wrong and must be resisted. It was the means of that resistance, Henderson judged, where uncertainty clouded the picture. They agreed that the best way of devising the means was to have a “Congress of the First Patriots.” At the basis of Patriot thought were “ideas of liberty resembling the old English ideas”, such as honest courts, free elections, freedom of the press, property ownership, and more. If resistance failed, he predicted, “political slavery” would result. Henderson advised that “all the attention of Britain must be drawn towards a measure big with the fate of the Empire.” Change the laws now or suffer upheaval.

Without using the term, Henderson’s letter described the arrival of a state of nature.

* * * * * * *

(before there were late-night comedians)

A state of what? There’s no such thing! Just another laughable remark from silly supporters of colonial rights.

A mocking sarcasm is the theme in a so-called “Meeting of the True Sons of Liberty” document circulating today in New York City. The unknown authors seek to draw an audience through mixing entertainment with current news and poking fun at political events. They build their arguments through lampooning and ridicule. It’s discourse through belittlement.

“Ebenezer Snuffle” was the secretary at the imagined event. Three men, including “Roger Rumpus”, led the meeting. The group agreed to fifteen resolves. The Fourteenth Resolve captures the overall spirit: “That the best Way of approving our Loyalty is to spit in the King’s Face; as that may be the Means of opening his Eyes.”

The point of the sarcasm was to accuse colonial rights supporters of hypocrisy, backstabbing, and bullying. Mock them and they will come.

* * * * * * *

(of the Eleven)

Isaac Winslow might have laughed at the sarcastic essay but he had other problems in front of him. Real stuff, not snarky stuff.

He is one of the Boston Eleven.

Today, 250 years ago, British General Thomas Gage, newly installed imperial governor of the colony of Massachusetts, has announced his list of thirty-six Mandamus Councilors. These men now comprise the imperially chosen and approved Council to serve with the governor and the elected Assembly. This is one part of the Coercive Acts, the Massachusetts Government Act’s mandate that the Assembly will no longer have the ability to elect the Council on their own. After doing so for the past eighty-three years—first granted in the colony’s Charter of 1691—now this responsibility is taken away from the Assembly and given by the British Parliament’s new law to the imperial governor. And it’s no joke.

Of the thirty-six named today, eleven have taken the oath on this same day. Isaac Winslow is one of them, the Boston Eleven.

Winslow, a Boston merchant, has family and business ties to two of the people who had received imperial licenses to sell East India Company tea last fall before the protest dump. Ever since, he’s been regarded as pro-imperial, pro-monarchy, pro-England.

But now, to raise his hand today for the King’s oath is to raise his hand as a target, starting tomorrow. He’s chosen to be linked to the suffocating Coercive Acts currently strangling Boston and Massachusetts. Anything is possible in retribution and revenge amid the dark, frightening atmosphere of now.

Every day, every cycle of sun, stars, and twenty-four hours has the potential to turn Winslow into a one-man state of nature.

* * * * * * *

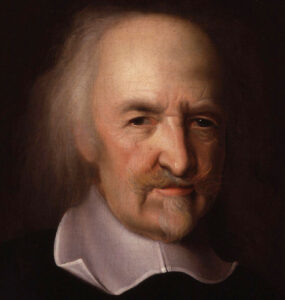

(Thomas Hobbes, nature designer)

Before law, before order, before government and every other public-civic arrangement of life, there is the state of nature. Thomas Hobbes coined the term and birthed the notion. Today, 250 years ago, the idea is alive and living, amongst the Calvinists reading their Hobbes.

Also

(the brother’s sister)

Older brother writes to youngest sister. He fears she’s worried about him and might be hearing nasty rumors about him. This letter, he hopes, will calm and clarify.

Sitting in London, Benjamin Franklin writes to Jane Mecom. He warns her not to listen to wild accounts that he’s been seeking an imperial appointment and salary. No, not at all, he assures her. He’s fully committed to the colonial cause, he adds.

It’s the final part of the letter that carries the most urgent feel between the lines. Do not—absolutely do not—share this letter with anyone under any circumstances, he writes and states and tells and prays. Keep it to yourself.

These are dark days for letters read by the wrong people.

* * * * * * *

An acquaintance of Franklin’s is in a room at Bowood, a stately manor home on an estate in Wiltshire, England. Lord Shelburne, estate owner and another of Franklin’s relationships, prepares to leave for a long tour of the European continent. He’ll travel with a guest, the occupant of this room.

The guest is in the room with a combustion going, heating a glass container filled with red mercuric oxide. Under heat, the substance changes and the guest captures the new state of the element. He marks it down in a notebook as “dephlogisticated air.” Yes, the guest nods, that’s what it is. It’s the only way the discovery makes sense within the accepted concepts of phlogistan.

Dr. Joseph Priestley has actually just discovered the fact of oxygen and destroyed the theory of phlogistanistics.

But he rushes out of the room. It’s time to pack and leave with the Lord.

* * * * * * *

The state of nature is always unfolding.

For You Now

(Van Gogh’s state of nature)

Revealing the existing.

It can happen under different conditions and through different stressors. The differents of them can obscure what’s truly at work. Combinations untried, until now, and sequences unmarked, until now, and fabrications unformed, until now—these are the developments of the elements that strike us as shocking and jolting but which far more often than we suppose actually rise into view with a new angle, context, or perspective.

And then we touch or tap or smack our heads and whisper, why, of course, how could it have been otherwise?

The discomfort and, let’s say it, despair before then is real. No point in denying that. No gain in claiming otherwise. Absorb, cope, and respond.

But don’t forget Priestley in his room. He’s using heat on high to release something already real. His first instinct is to label the thing for a box smartly built. And he’s in a hurry to go somewhere else.

Heated—Labeled—Hurried—In discovering what’s already in, from, and through, the state of nature.

Suggestion

(Your River)

Take a moment to consider: in the heat, labeling, and hurriedness of today, what might we already know that would feel like a discovery?

You’re always welcome to reach out to discuss. Be well.