Americanism Redux

April 11, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Your money. It’s in your account. How much? It’s on your credit card? How much? It’s listed on sheets and screens. How much?

You access your money through passwords, numbered codes, facial recognition.

You’re reminded of it every time you see a person holding up a sign and asking for whatever amount the driver or passerby can spare.

And a rock music group called Pink Floyd performed a song about it.

https://youtu.be/2aW7HweAf3o?si=3-Hf4ZCAD1PYmL-I

* * * * * * *

(Anne Green)

Anne Green, owner-operator of the media company known as the Maryland Gazette and left to her by her dead husband, learns today that the law is passed. Thank God, she says.

She’s got the printing contract tied to the law.

Today 250 years ago the legislature of the colony of Maryland—the Assembly—passes a law that calls for the printing of L480,000 in indentured bills, a form of money. Half the amount will be for loans, one-sixth for government expenses, and one-third for replacing worn-out bills currently in circulation. The new money will be split among denominations ranging from one-ninth of a dollar up to eight dollars; the Spanish word “dollar” is a common thing as of spring 1774, a testimony to the imprint and power of the Spanish Empire. The new money will be redeemable in London, can be exchanged at fixed rates for gold and silver, and is good as credit so long as people have faith in its worth.

Anne Green meets with her son Frederick—she’d birthed fourteen children with only six surviving—and together they begin plans to print the legislated currency.

The Greens put a new design on the Maryland money, the first time they’ve done so since Anne took over the enterprise.

* * * * * * *

(Royal River, near Dr. Cutter’s property)

Dr. Ammi Ruhamah Cutter hears the news out of today’s town meeting in North Yarmouth, colony of Massachusetts (now Maine). They voted to pay him a grand total of L1 (one “Pound”, a unit of currency) for a little over three acres of his land near Royal River. That’s the chunk of his property that will be used for a new road being built by town officials. A former doctor for the first unit of organized guerrilla fighters back in the French and Indian War—Robert Rogers’s “Rangers”—Cutter’s portion of the road will carry travelers on horseback and carriages alongside his well-known property.

Money was the town government’s way of paying him for the trouble and bother. Paid out of public coffers.

* * * * * * *

(the stuff of his analysis)

Robert Carter Nicholas explains to a colleague and neighbor in Williamsburg, colony of Virginia, the complexities of liquor as a revenue-generator for financing local government. He tells in detail of the problems of enforcing liquor “duties” (taxes), including corruption, unfairness, and the bumpy layers of bureaucracy. At the bottom of it all, he states, is the “vigorous Exertion of the Powers of Magistracy”, or the people in formal positions of power, in other words, invested with public power–the only chance to do it right is to exert maximum power from public office. Nicholas’s insights re-tell the existing imperial-colonial crisis from the opposite end of the telescope: it’s liquor, not tea; it’s between the people and the powerholders inside a colony, not an empire; it’s getting revenue for local government, not imperial government; it’s magistrates, not Parliamentary members.

The binding DNA in Nicholas’s analysis is money. The private holds it. The public prys it away. But only if enough power is used.

* * * * * * *

(like Watson’s freshly painted vessel)

Alexander Watson is a young merchant living in New York City, colony of New York. He keeps a notebook, meticulous in depth and range if a bit scattered in chronological entries. He stuffs two kinds of details into his notebook, Mammon and God, the records of money spent and money gained as well as prayers, hymns, and poems of the spirit. It’s an interesting decision to pair up these two categories in the same booklet. Today, 250 years ago, he scribbles a line about receiving his schooner after paying Thomas Barrow to paint the vessel. Barrow pockets L3 and some coins, all money printed or marked in New York. Watson has a fresh coat of paint on his boat.

A customer has a need, a worker has a skill, and money changes hands.

* * * * * * *

(this museum is housed in the interior of a colonial Virginia jail, like the one in Staunton)

A Pennsylvania colonist, Aeneas Mackay, needs money to get out of a Pittsburgh jail. Actually, he was removed from jail after only a few hours, when his captor, Dr. John Connolly, demanded Mackay and two others travel to Staunton, colony of Virginia, where Connolly expects them to report to the sheriff there for re-imprisonment. That’s where Mackay will need his bail money. He’s terrified to leave his wife and children in Pittsburgh with Connolly having influence over a mob hell-bent on taking control of the town in the name of himself, the colony of Virginia, and its royal governor, Lord Dunmore. Mackay pleads by letter to friends to come with bail money as fast as they can. It’s the latest incident in a worsening dispute.

Money could make the difference for a family seeking safety.

* * * * * * *

(the original source of his money)

Getting money can take time.

In York County, located in the eastern half of the colony of Pennsylvania, Martin Eichelberger is 57 years old with a large family. He’s been in the colony since he was 12 years old when he arrived as a German-speaking immigrant. He’s worked hard as the proud builder, owner, and operator of the Golden Plough tavern in Yorktowne. He’s gathered a modest sum of money for his family, supplementing his income as keeper of the town jail. And now he’s receiving a another term as one of the county’s justices of the peace. Eichelberger has specialized in cases involving the county’s black population, whether free or enslaved. He’s seen the struggles of people who don’t have a lot of money and the desperation they show when trying to cope with the legal system.

Watchful of the money he’s accumulated, Justice of the Peace/Specialized Judge/Jailkeeper/Tavern Owner Martin Eichelberger is wary of English-speaking Britons in York County who insist danger looms, a crisis is at hand, and his freedom to earn a livelihood is at risk. He’s skeptical of the words heard in his second language.

* * * * * * *

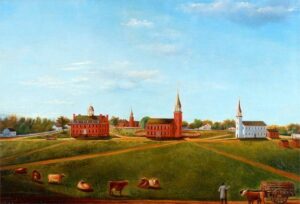

(New Haven, the opposite sight of the raucous protest where people fill the green)

Bold plans or wild schemes? Either can cost money, and usually much more money than anyone expects at the start.

More than 500 people have assembled at a protest meeting in New Haven, colony of Connecticut. They are a massive proportion of the town. The protest isn’t about tea. They’re angry over constant efforts by a group of land speculators, politicians, and restless colonists who’ve joined together to push a new Connecticut settlement in the Susquehanna River valley of Pennsylvania. Governmental elections in Connecticut are happening and many towns have organized these protest meetings to demand the shut-down of the “Wyoming” settlement. Anti-Wyoming protestors suspect that the Connecticut government will be manipulated into paying money for the enterprise and possibly for any armed force sent to a potential clash in Pennsylvania. No one involved in voting can avoid taking a stance on the Wyoming issue.

Money follows plans, and that’s what worries them—their money, following someone else’s plans.

* * * * * * *

(the model for The Preacher)

“Stay calm”, he shouts.

“The Preacher” is the adopted name of someone who writes a special essay for today’s edition of the Boston Gazette. The Preacher implores readers to remember that God has always favored New England since its founding 154 years ago. “Therefore,” writes The Preacher, “let all the Friends to Liberty and their Country, still trust in GOD, and He will tread down their Enemies and cause Liberty to triumph over all her Foes in America.”

Is your money safe? The Preacher would say it doesn’t matter. It all falls under divine sovereignty—if done for God’s honor, protection, and if done for God’s dishonor, destruction.

* * * * * * *

(the “embellishment” of Samuel Adams)

Money likes fame. Becoming the subject of talk around tavern tables, church pews, and family hearths can draw money to the person who is the topic of discussion.

Samuel Adams is mentioned on the cover of the April issue of “The Royal American Magazine, or Universal Repository of Instruction and Amusement.” Inside the magazine is a printed drawing of his face, an “embellishment” as it’s called, based on a painting of him, another sign of his fame. As one of the leaders of the colonial rights movement, he’s become popular with a large group of people in Boston. Years ago, no one bothered with him. Now, they buy him meals, drinks, gifts, and more. He doesn’t do it for the money or the things it buys. The dollars and coins just come along with the public visibility and community influence.

Money tied to a cause is the flame on a candle—it can go out in the next moment.

* * * * * * *

(John Adams)

Cousin to Samuel is John Adams, and he’s noticing a change in some people he sees. The opponents of colonial rights are “in such a state of Humiliation…Wherever I go, in the several Counties, I perceive it, more and more.” He’s perceiving a greater kindness, modesty, and moderation in their conduct toward colonial rights supporters. John Adams checks himself—don’t be fooled into thinking they’ve actually changed, reminds he to he, it’s merely because of a shift in momentum. That in itself could shift again, Adams realizes, with whatever news arrives on the next day’s ships.

And with this reminding realization, Adams touches a deeper chord of truth: “The first vessels may bring us tidings, which will erect the Crests of the Tories (opponents of colonial rights) again and depress the Spirits of the Whigs (supporters of colonial rights)…I am of the opinion that I have been for many Years, that there is not Spirit enough on Either side to bring the Question to a complete Decision—and that We shall oscillate like a Pendulum and fluctuate like the Ocean, for many Years to come, and never obtain a complete Redress of American Grievances, nor submit to an absolute Establishment of Parliamentary Authority. But be trimming between both as we have been for ten Years past…Our Children, may see Revolutions, and be concerned and active in effecting them of which we can form no Conception.”

In other words, life’s predicament is stuck in the middle with no resolution and neither group capable of seizing an outcome, until a new generation answers the question definitively in the future.

The money won’t decide.

Also

(he’s reassuring)

Lord Dartmouth, a key advisor and official in the prime ministry of Lord North in the British imperial government, laments a person he regards as somewhat of a victim in the current crisis—former Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson, now replaced by General Thomas Gage.

Dartmouth writes to Hutchinson today to reassure him and offers his thanks and regret to the former governor. Dartmouth urges Hutchinson to understand that Gage’s appointment is temporary and “will most probably not be of long duration, and it is the King’s intention that you should be reinstated” as governor. The timing of that reinstatement, Dartmouth predicts, will depend on Gage “as Commander-in-Chief” being needed elsewhere.

Interesting appearance of the phrase “Commander-in-Chief.”

* * * * * * *

(an old mission to the Pimas Bajos)

Today, 250 years ago, the daily routine continues for people in another empire, that of the Spanish in New Spain. Money plays a role.

Natives from the Pimas Bajos tribe look at a church that has been paid for and built for them. The building is a gift of sorts from Spanish authorities in the Catholic Church, a peace offering to the Pimas Bajos after their failed uprising in the rugged mountains of northern Mexico. Catholic priests bless the building and encourage the Natives to worship in ways that feel comfortable to them, especially in the use of saints, spirits, and holy items.

Meanwhile, to the west, in the south of California, the Mojave Natives live near the Spanish mission of San Gabriel. Catholic priests describe the Natives as impoverished in the midst of a land that could yield great plenty. Food and water are scarce, and the health of domesticated animals is so bad they can barely move. Relations between the Spanish and Mojave are tense. Some Catholic officials are frustrated by the extent of poverty, and some Mojave regard the Spanish as arrogant and dismissive. In the desert mountains, they glare at each other from different sides of the dollar chasm.

For You Now

(placements)

Let’s think of money as a single word. It’s the bull’s-eye in the middle of concentric circles. What words do you place in the next circle surrounding money? Presumably, these will be the words you most closely associate with money. And then what about the third circle out? Not quite as proximate but still your mind sees a path of connection for the money-ish words of the third circle, yet something accounts for the distance between the center and the outer rings. And then beyond?

Are the placements of your money-words more a reflection of how your life has gone or where your life is right now? And what happens if you alter the exercise and think not about your life but about the broader life of a community? Of a nation?

Our stories in today’s entries fit in various places on the concentric circles. Some very near the bull’s-eye, some farther out. For work. For safety and security. For compensation. For reflection of power and spending on the public. For sustainment of a cause. The movements of the placements will often involve a wrenching change.

And when those ships mentioned by John Adams, those yet to arrive but which, inevitably, will appear soon on the ocean’s horizon, money will be part of the story to be told. A bull’s-eye makes a tempting target.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: in what form is money having the biggest affect on the American mood this year? Does money have an unusual impact on collective mood?

(Your River)