Americanism Redux

July 18, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

The only passage to the future is through the present. No other door opens up on tomorrow. Only today.

* * * * * * *

(the land of Nomini Hall)

In the final scorching of a summer day, the sun sat for a moment on the distant trees. A lush green thickened the woods and meadows after recent storms. Lower and lower through the humid, shimmering air, a last ray of sunlight blasted from the horizon. The fiery sun winked goodbye, the glow of orange and pink waved in retreat, and the quiet of blue folded over the land.

Beads of sweat on his face, Philip Fithian watched from his second-floor bedroom window at Nomini Hall in Westmoreland County, the northern portion of the colony of Virginia. The heat was gone and he was glad.

He ventured down the wooden staircase and out the house into the plantation gardens. He felt the soothing air of dusk. Refreshed, he began to stroll among the flowers and bushes. He met others who, like him, had waited until the sun’s descent before leaving the indoors. Pleasantness produced tonight’s society, he noticed, as “the whole Family seems to be now out”. For a while, the impossible was true with “Black, White, Male, Female, all enjoying the cool evening.” The sight cheered him.

Philip Fithian returned to the house owned and occupied by Robert Carter and his family. In their rooms, one by one, the candles went dark. An oppressive heat remained and the wooden floors, walls, and ceilings felt ancient. In the trees and tall grass beyond the gardens, crickets and frogs added their sounds to the night. Motionless, on the other side of the earth, the sun waits to blaze in the next infernal dawn.

* * * * * * *

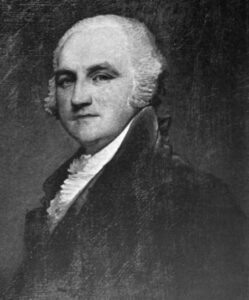

(Bryan Fairfax)

The constant storms that boiled the air and moistened the wood inside Nomini Hall had similar effects on Towlston Grange, near Virginia’s Great Falls and home to Bryan Fairfax. Fairfax wiped his brow and wrote a letter that feels as otherwordly as Fithian’s thoughts in the Nomini garden.

“It is incredible how far a mild Behavior contributes to a Reconciliation in any dispute between Man and Man,” Fairfax writes to his friend George Washington, “and how much the Spectators are always engaged on the side of the Man of Moderation.”

The core of the problem, Fairfax observes, is the protest movement’s belief that Parliament has only a sliver of authority in the colonies and maybe not even that much. In such an environment, Fairfax urges Washington to hold to, and never deviate from, politeness, centeredness, the harmonious balance between extremes. This is Fairfax’s advice to his friend on leadership in the current crisis.

* * * * * * *

(Fairfax Resolves)

While Fairfax pens his letter to his friend, that very friend is with another friend and together, at the plantation called Mount Vernon, they’re writing the “Fairfax Resolves.” The words authored by George Washington and George Mason do not conform to the advice coming from Towlston Grange.

The “Fairfax (County) Resolves” are blunt, hard-hitting, and anything but moderate. The twenty-four Resolves embody everything that Fairfax warned against. Their immoderation includes drawing a distinction between conqueror and conquered, between subject and slave, between opposition to mere policies and the “preservation of our Lives, Liberty, and Fortunes”. They dutifully seek to send a petition to Parliament, then to the King, and if nothing avails, after “our Sovereign, there can be but one Appeal”, a dark hint of ultimate action.

Today, 250 years ago, a group of Fairfax residents—white men, propertied, many keeping enslaved people and some not—sign off on the Fairfax Resolves on the day that Fairfax’s letter travels to Mount Vernon.

* * * * * * *

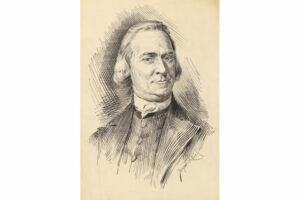

(Samuel Adams)

Today, another letter is on its way to another Virginian. Samuel Adams of Boston has written to Richard Henry Lee owner of the estate Chantilly-on-the-Potomac. Adams writes, “Should America hold up her own Importance to the Body of the (British) Nation, and at the same Time agree to one general Bill of Rights, the Dispute might be settled on the Principles of Equity and Harmony restored between Britain and the Colonies.”

The notion is remarkable for the writer-recipient pair. Each man has forged a reputation for boldness and risk-taking in the conception and advocacy of colonial rights, whether in Westmoreland County, Virginia, or Suffolk County, Massachusetts. Each man is, to their opponents and to the targets of their power and influence, a firebrand and a radical.

Yet here they are, the parchment between them marking moderate progress on a journey and not the destination of travel itself.

* * * * * * *

(the home of Miles Brewton)

Other travelers are walking the line of movement laid out in the Adams-to-Lee letter. Miles Brewton, a supporter of colonial rights in Charleston, colony of South Carolina, is pleased that a set of delegates from the colony has been chosen to participate in the “general congress”. Moreover, Brewton applauds that “their powers are unlimited” in adapting to conditions and circumstances which might face them in Philadelphia. Brewton sees it playing out like this: first, the congress develops a petition and also a bill of rights; second, congress selects from itself a delegation to deliver them personally to London; and third, if nothing results, launch the economic bans and boycotts. Set aside the musket, Brewton concludes, “Unanimity must be the great leading Star”.

* * * * * * *

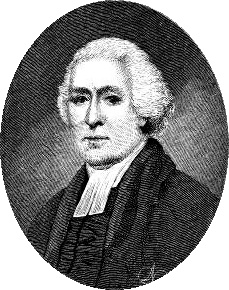

(Ebenezer Parkman)

The third item seizes the mind of Ebenezer Parkman, a Christian minister in Westborough, colony of Massachusetts. A local group of colonial rights supporters has completed its visit to Parkman’s house and church. They want him to publicly approve the town’s participation in the expected economic retaliation against the imperial policies punishing Massachusetts. Parkman had inched closer to a more aggressive anti-imperial stance when the group adopted his suggestion a few weeks prior of a public day of prayer and fasting. But he’s still holding back, asking today 250 years ago for more time “to review” the proposed plan for economic bans and boycotts in the colony. In moments like this, thought, reflection, and prayer are vital actions in Parkman’s leadership.

* * * * * * *

(the data)

The list is impressive. Downright impressive.

Governor Josiah Martin of the colony of North Carolina has completed his list of laws recently enacted the colony’s government. He needs King George III, or perhaps more accurately someone advising the monarch, to give formal approval before the new laws formally go into effect. That’s how it works in the British imperial-colonial system.

There are thirty-two newly adopted laws on Martin’s list. They range from land boundaries to local regulations to church organization to legal and court administration. On the latter item, Martin is confident the somewhat lengthy disputes over judicial courts has been resolved.

Viewed another way, thirty-two is a data set. A look at the data must tell you one clear thing: a functioning colonial government exists in North Carolina. What accounts for it? No one has bothered to ask and no one has thought to answer.

Is moderation alive and well in North Carolina? Is a model to be found where colonial rights work on a level acceptable within imperial authority? Or is the data set a slightly different version of Philip Fithian’s garden stroll where he sees all people, together, enjoying the cool-down of dusk and the brief lowering of outdoor temperatures.

Sooner or later, you must enter the sweltering house and feel the rising sun.

Also

(Gilbert White)

Gilbert White takes out his journal on his birthday, today, 250 years ago. He’s in Hampshire County, in the English countryside and when he’s not preaching the Word of God he’s writing in his journal about the miracles of nature all around him.

Lately, after the mowing in the meadow, White has been writing about the swallows, the small birds darting through the air to drive off the owls and the magpies. These larger birds often give up and fly off in frustration, unable to avoid the jabs and strikes of the swallows.

It’s an interesting observation, isn’t it? A large creature of power flailing at smaller, weaker, and yet somehow more elusive adversaries, committed to protecting their homes and offspring.

Happy Birthday, Gilbert.

* * * * * * *

(Omiah’s royal introduction)

Omiah is a native Otaheite, of the island later called Tahiti. Today, 250 years ago, he is still absorbing yesterday’s visit to the King George III and Queen Charlotte of England, presented to the British monarchs by Joseph Banks and Dr. Daniel Solander, members of Captain James Cook’s first expedition and well-known naturalists in Britain and northern Europe. Unspoken in public but strongly evident in private, closed-door conversations within British aristocracy, Omiah has stirred interest in native sexual practices and habits. Omiah’s island—beyond Britain’s city smoke and country hillsides—conjures imagery of a more natural and freer world.

* * * * * * *

(today’s legacy)

Let’s see. “Cobbler”. Write that down.

Oh, and “Subject”. Write that down, too.

“Cobbler and Subject.” Pretty well sums up him and his life. Nothing else to know. Move on to the next one.

We’ve got other people and lives to summarize in Hesse, a German principality linked to the father and grandfather of George III’s House of Hanover. Write ’em down and sum ’em up.

Either term stand out to you? The skill you may know is all you need to be known for, the product of your hands or back or feet or whatever. The status you have is easy to label, which is to say no real status at all other than to be ordered, commanded, dictated to, a human piece pushed into this or that square. When necessary, that reality will require you to fight in a war of the monarch’s wishes.

Cobbler and subject—that’s the phrase next to Johann Adam Birkenstock, of Bergheim, in Hesse, today, 250 years ago. Two years from now some of Birkenstock’s neighbors will be dragged off to fight for the British Redcoats in the New World.

* * * * * * *

(the assumed source of American rescue)

Joseph Johnson is in London, England doing every trick he knows to do in pursuit of money. He’s the London business agent for a partnership of merchants living in Annapolis, colony of Maryland. Today and earlier this week, 250 years ago, he’s been mixing promises, threats, and intimidation to sell off or trade off items shipped to him by the partnership. Johnson sees that the goods he’s selling has an active market in London, which includes tobacco that pulls in an attractive price. So, overall, he’s happy. But underneath his happiness is a frenzy of activity that he has to use to close the deals, a draining energy that he has to summon to convince buyers to say or nod “yes”. Johnson verges on exhaustion.

These are the people and places that supporters of colonial rights believe will make the crucial difference—shut down the commercial and economic transactions and a great merchant cry will go up that changes the minds and hearts of the British imperial government.

The docks and the counting houses will rescue the Americans. That’s the view of many colonists on the other side of the Atlantic.

For You Now

(middle, mid, and moderate)

Bryan Fairfax, Ebenezer Parkman, Miles Brewton, even Samuel Adams. We see in today’s entry that each of them has at least partial sight on something less than the extreme. They see a point closer to the center between the ends of doing all and doing nothing. It’s the moderating middle that they seek.

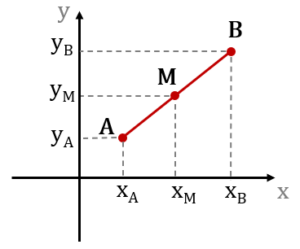

But the middle of what, exactly? The center of where, precisely?

I think we don’t have full appreciation of how tangled and twisted the path to the middle can be.

The understanding of middle and center depends entirely on what you understand the two extremes to be. Shift the polar pair—whether one end or both—and you completely upend where the middle plots and locates. And even if or when you find it, the calculus can recalculate and you discover yourself standing alone on a far edge. The middle can move without a second’s notice.

Want to know how fast the middle moves? Ask the owl and the magpie. The middle can move at swallow speed.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: have you seen the middle move thus far in 2024?

(Your Mid-River)