The trends are bad, no matter what they tell you, but that’s not the whole story. More to tell, more to know. Day 47, October 24, 1918.

Today, people are jumping in, taking action, making a difference in the circles around them. Water on the rock—though pressures from influenza do wear us down, at the same time they reveal beauty, worth, and essence. As tidal waves crash over them, people are often capable of so much more than they once believed.

The social work founder—and inner-city pioneer—Lillian Wald works with her newly-organized Emergency Nurse Council in immigrant neighborhoods in New York City. Today, through her patient touch, inspectors usually employed at the Tenement House Authority change job assignments. They’re now out going house-to-house to check on families who may have been overlooked in the mad crush of influenza. They’re helping immigrant families get care, get help, get better. As the cross-trained staff walk the streets, Wald informs executives of local emergency health districts of their new activity. She’s learned it’s a good idea to communicate with other leaders.

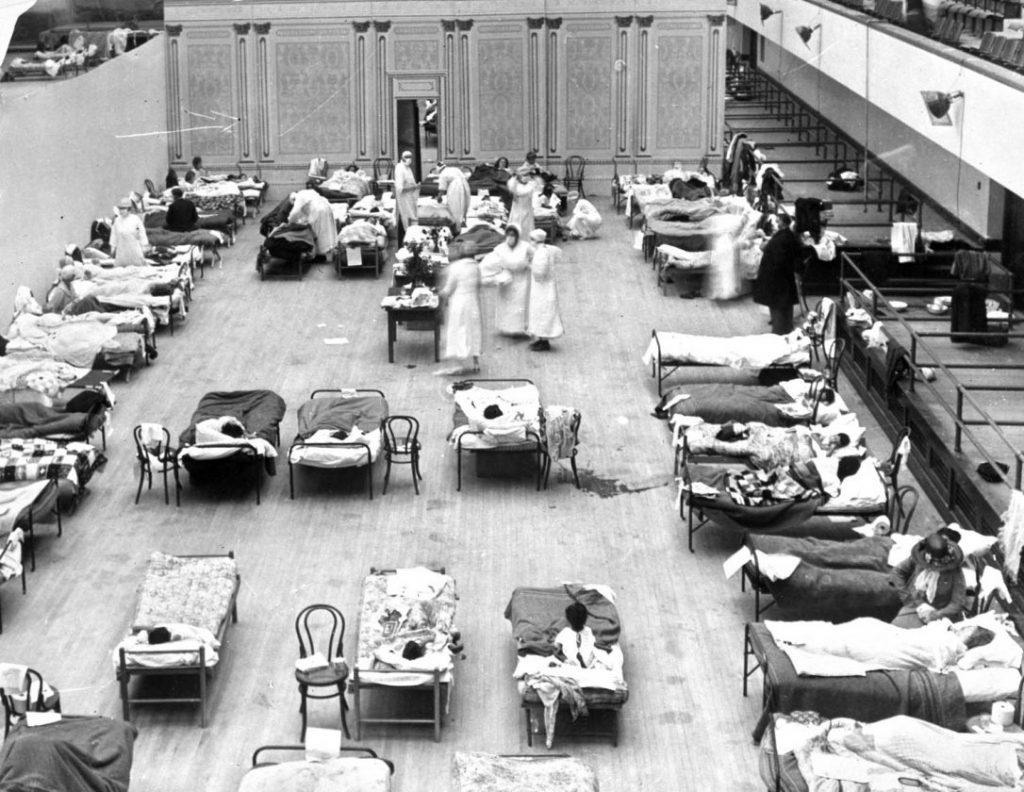

In Wald’s home state of Ohio, the Knights of Pythias are a private, nonsectarian fraternal group dating back to 1864. They’re the first such group chartered by the US Congress and today the local chapter in Salem, upends everything they know. They give their meeting hall to the community as a temporary hospital. Where cribbage was normally fought over, patients will now be treated and cared for. The Knights call for everything—volunteers, goods, anything that helps open a hospital overnight. They don’t worry about rules, they don’t argue over procedures, they just dive in and do it. The Salem Knights gallop head-long into influenza.

Town councils fight the battle, too. In Chippewa, Wisconsin the group of elected leaders state flatly that they’re all opposed to spitting and all in favor of mask-wearing. They urge residents of the town to adopt the same view. In California, San Francisco’s local officials go another step and make the voluntary mandatory—they’re the first such group in the nation to make it a law to wear a mask. Disobey by the Bay and you’ll be punished.

New Mexico has no state health department, so it’s all being done on a local-by-local basis. In Farmington a couple of weeks ago the mayor imposed on his own a quarantine across the community; folks allowed it because they knew and trusted him. Today, despite his efforts, influenza is now in the town, according to the magically-named “Times-Hustler.” Somewhere in the readership of the Hustler live their versions of Lillian Wald and Knights of Pythias. They’ll rise up. Elsewhere in the state, physicians like Dr. C.M Grover already pull the load—he’s treating patients most hours of every day, including giving comfort to those about to die. Among the dead found on his rounds today are “three old Mexico Mexicans.” That’s how they live their maps in this 6-year old state sharing a name with a neighboring country.

The New Mexico newspaper featuring Grover’s work also features a curious statement an inch below: Palmist (and no, not psalmist—the silent “s” is a missing “s”, which says a lot): “Tells past, present, and future. Teaches the science. Guarantees satisfaction.”

Not everyone can be Lillian Wald.

And not everyone has the chance to be Lillian Wald, either. Some have the doors slammed on them, the floor burned away beneath their feet, and walls made not of wood but of iron bars.

But yet, still they come. To help, to inspire, to meet a challenge and do a duty they hear and feel in heart and soul.

Here, today, thanks go out to a person who is Wald in fact as well as spirit.

Unknown in age, unknown in education, unknown in condition. Except for slivers of other things. She is from land next to ancient highlands and the visible air that names them—between Blue Ridge and Smoky Mountains. She lives in the harsh, racially segregated villages of western North Carolina. She is African-American. And from the branch of a scarlet oak tree the birds sing her name.

Beulah.

Beulah Martin.

She is a volunteer nurse. She has run out of her home to treat the sick, tend the dying, and teach the living. Given the location, the chances are good she is the only one who visits the homes of other African-Americans who are sick with influenza. Regardless, a local newspaper cites her and a group of other women as “each and every one a heroine in the truest, broadest, and noblest sense of the term, and they have earned the everlasting gratitude of our community.” The newspaper’s inclusion of her is a statue without a stone, an award bathed in a light that she and her brethren see. Deserving of so much more and willing to set it aside, she returns home, in good health, thank God, and hopes that the worst is over.

The over of it can’t be seen now. The damage is deep and still unfolding. Today’s edition of the Wall Street Journal shows influenza’s effect on people and their livelihood: “in some parts of the country has caused a decrease in production of approximately 50 percent and almost everywhere it has occasioned more or less falling off. The loss of trade which the retail merchants throughout the country have met with has been very large. The impairment of efficiency has also been noticeable.”

The Journal concludes: “There has never been in this country, so the experts say, so complete domination by an epidemic as has been the case with this one.”

A thought for you on Day 47, April 28, 2020, forty-seven days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—the vast army. Beulah Martin belongs to Lillian Wald, who belongs to the cribbage-playing Pythias of a small town, who belong to the exhausted Dr. Grover, who belongs to the retrained workers going house-to-house on the streets of New York City. So it goes. They are the people coming from the homes, from the hills, from the offices, from the outside. They are not always experts. They are not always right. They are not always indomitable or invincible. They’ve also had things done to them—on a variety of scales, levels, and degrees—that should never have happened. But they had. And still they come. Because, yes, the demand is there. Because, more than that, they have a courage uncovered. A gift unsealed. A good now done. The wave rolls and soon will roll again. I hope the sound of your name as well as mine might, for a moment, in a color of the air, be heard from branch of the scarlet oak tree.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)