Thank you for seeking out more information from the experience of an unknown leader, 32-year old Edna Fletcher. Pictured above, she was a significant healthcare leader at Methodist Hospital (now Indiana University Health Methodist) in Indianapolis, Indiana. Below are brief points from her experience. I believe they can help you in your leadership right now and the days ahead. (Contact me at 317-407-3687 if you have questions or wish to discuss further.).

First, Fletcher informs her hospital CEO that she is willing to organize and lead a group of volunteers to help fight the pandemic. It is Monday, October 7, 1918. The hospital is an advanced organization, leading edge in local healthcare.

>Fletcher has a track record of individual leadership in healthcare both in the hospital and in a previous organization.

>Her decision occurs as local and national events are swirling in confusion and turmoil. Global war, the onset of unexplained illness, and local tensions among ethnic groups are only some of the ongoing problems.

>The hospital is trying to stay ahead of war-related events and demonstrate its value in its city and community.

Lesson for you: a moment arrives when a single point of focus will require you to set aside important and troubling controversies, whether internal or external. A decision must be made. Fletcher recognized the purpose of herself and her team as well as the need of a broader community. That was enough for her decision and action. My question to you—how do you describe the decision-making culture between you and your boss, and between you and your team? What works well and what do you wish would work better? Does it affect that culture when sudden events hit?

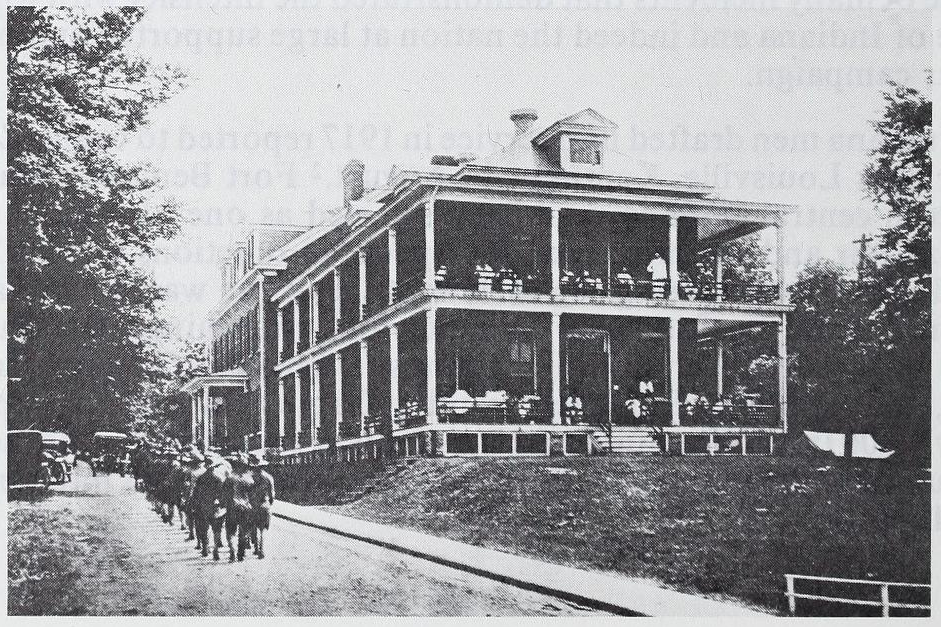

Second, Fletcher organizes thirteen volunteers among student-nurses at the hospital. The group travels approximately fourteen miles via train to Fort Benjamin Harrison. The Fort is one of Indiana’s epicenters for the pandemic, among the worst such sites in the Midwest. They head into the teeth of the crisis. Shown above is the hospital at the Fort in 1918.

>The volunteers are all young women, living away from home and in their first career or profession. Beyond their current nursing courses, they have no formal preparation for this type of situation.

>Conditions at the Fort are awful. Nearly 3000 soldiers are ill. No treatment exists, only caring for comfort is available to Fletcher and her volunteers for the afflicted soldiers. They can only watch while dozens at a time die silently.

>A group of investigators arrive at the Fort on Friday, October 11, 1918 to determine if widespread community rumors are correct that mismanagement has worsened things at the Fort. In addition, local tensions between ethnic groups continue to boil over, including among people located not far from the Fort.

>While at the Fort, two of Fletcher’s thirteen volunteers die from influenza.

Lesson for you: you will not have full control over where or how the major decision you just made unfolds; part of the gap must be filled by you as a leader and by your team as individual members. Fletcher could not ensure her volunteers were entirely ready for service. She also couldn’t ensure that conditions around them would play to their strengths and gifts. My question to you—is there a personal experience you are drawing upon in your leadership right now and in the days to come? Does that experience extend to dealing with improvising and adjusting hour-to-hour? What’s your ability in helping your team members cope with severe stress?

Third, inexplicably, influenza disappears from the Fort and elsewhere in the city and community. Fletcher and her eleven surviving volunteers leave the Fort and return to their home hospital.

>By early November 1918 the disappearance of influenza is accompanied by two explosive changes. First, the global war ends. People celebrate. Second, an off-year congressional election produces a stunning result with President Woodrow Wilson’s Democratic Party suffering major defeats in Congress. At the moment, it is unclear what effect this will have. What’s certain, though, is that an effect will come.

>Then, without warning, influenza reappears in mid-November. Like before, several steps are taken in the city to reduce the illness’s impact, including consideration of arresting people for spitting in public.

>On Thanksgiving Day, an event with massive meaning unlike any other in living memory, Fletcher develops a cough, fever, and congestion. She goes to the Nurses Home to rest. Four days later, she dies. Shown below is the 2020 location of where the Nurses Home once stood in Indianapolis.

>The hospital’s board of trustees issues a special commendation on Fletcher’s behalf.

>She is taken for burial in a particular location. It is not Indianapolis, Indiana where she worked. It is not Ellettsville, Indiana where she was born and family still resides. It is not Fort Harrison in Lawrence, Indiana where she provided the inspiring example of what a later era would call servant leadership. Instead, she is buried in a cemetery in Lafayette, Indiana where she had her first position of leadership in healthcare, as a superintendent of a nursing school. It is an intriguing choice.

Lesson for you: this event will end and the illness will reach a final, closing stage. You will help—or will have the opportunity to help—the shaping of the larger meaning, the more enduring meaning for you and your team. Other things will shape it as well, but absolutely do not ignore your own contribution to the living idea. My question to you—when was the last time you did this, that you helped mold a living idea? This undertaking is critically important because it enriches purpose and, make no mistake, will inform the next time a shocking major event unfolds for you and your team.

Thanks for reading. All the best, Dan