TTP: The Similar Opposite

Andrew Jackson as the first Donald Trump, Donald Trump as the second Andrew Jackson. As many of you know, I’ve been among those who have asserted that a link connects these two American Presidents.

I also believe a link connects their opponents. The people who opposed Andrew Jackson share quite a lot with those who stand against—or “resist”, to use their term—Donald Trump. You’ll see and hear similar words and similar emotions in the two opposition camps. Whether aimed at Jackson or Trump, opponents assert that a grave threat exists to the nation, to the American system of government, to the way of life they believe embodies the best future.

In the short term, opposition can be nothing more than that—the act of opposing. Its existence will account for its continuance. At some point in time, however, the state of opposition will need to transform into an actual alternative. The alternative will consist of a leader, a set of promised actions, and the methods and messages for communicating to audiences.

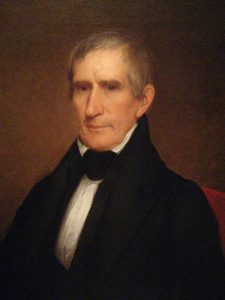

Over time, the opposition to Andrew Jackson found its most effective visible form in one person. He was William Henry Harrison. Harrison emerged as the chief opponent of Jacksonians by the end of Jackson’s second presidential term (1836). Four years later, in 1840, Harrison stood atop this opposition and won the presidency in his own right.

What does Harrison tell us about post-2017?

The power of Harrison’s appeal was in what I’ll call the “similar opposite.” The people who elevated Harrison’s candidacy decided to embrace Jackson’s broad traits while emphasizing specific differences with Old Hickory.

Political media of the Jacksonian era captured the idea. A newspaper writer at the Ohio State Journal in 1836 stated, “If it was right to elect General Jackson because he was a favorite citizen, and not the candidate of officeholders, it is right to elect General Harrison on the same principle.” Another news writer in Ohio narrowed the point further: “Harrison takes with the people.”

Like Jackson, Harrison was a general in the American army. Like Jackson, Harrison had a storied wartime record against Native Americans and the British. Like Jackson, Harrison took a harsh approach in policies related to Native Americans. Like Jackson, Harrison’s adult life was identified with the “west,” Indiana, in his case. Like Jackson, Harrison was a man of money whose wealth was somehow seen as different from affluent residents of cities and larger towns.

But unlike Jackson, Harrison was a quieter sort, unaffiliated with killing in pistol-packed duels, and not known for rage and violence in his day-to-day conduct. And he didn’t hurl words of anger and resentment toward people identified with “officeholders”, as the newspaper writer put it or as we would say today, “the Establishment.”

Using a cultural mirror, many Americans of the late 1830s could see William Henry Harrison and Andrew Jackson as similar figures. Using a personal or behavioral mirror, those same Americans saw two different men. Harrison was the pro-Jacksonian in social sympathies and the anti-Jacksonian in manner and morals. And rather than undermine his candidacy as proof of contradiction, the co-existence of the two views served Harrison well as a competitor to Jackson, Jacksonians, and Jacksonianism.

This “similar opposite” may be equally valuable to Democrats in the late 2010s. A winning candidate in the next presidential election could resemble Trump in “x” but differ from Trump in “y.” The x-y pairing, if it holds true to the example of Harrison, will be the key feature of the next campaign.

So, who knows, maybe we’ll see a Democratic nominee in 2020 who resembles the deep celebrity name-recognition of Trump without the personal baggage. Oprah, anyone? Is she the William Henry Harrison of our time?

Action-Point: the decision to oppose faces two junctures—one is the extent to which opposition is partial or total, and the other is the clearest way and form in which to express opposition.

Next time: censure and Jackson, censure and Trump