TTP: The Presidents and the Judges—The Lessons of a Saturday

Today, February 7, a federal court hears the appeal of the government’s attorneys on behalf of President Donald Trump’s executive orders on immigration. You and I can find an important story from a Saturday in early March, 185 years ago.

I invite you to stay with me for a few minutes while I provide you with a perspective on this emerging struggle from the “first Donald Trump,” seventh President of the United States, Andrew Jackson—who in 2017 is a fresh-faced addition to the walls of President Trump’s Oval Office.

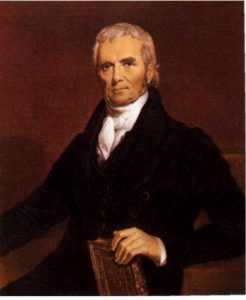

On Saturday, March 3, 1832, President Andrew Jackson absorbed news of Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall’s ruling against him. Marshall (seen above) and his Supreme Court announced that day they were overturning a Georgia law that had supported one of Jackson’s major policies, the removal of Native American tribes from the eastern United States. In an issue that meant much to Jackson personally, the president had lost in Marshall’s Supreme Court.

How did Jackson react, and what does that reaction suggest for the current president in 2017?

At the heart of Jackson’s reaction was the personal. Jackson detested John Marshall as one of the symbols of the old guard, the establishment that Jackson had defeated in 1828 to win his first term in the White House.

Jackson further despised the lawyer arguing the case against the government, William Wirt, formerly Attorney General under Jackson’s predecessor, John Quincy Adams. Jackson eyed Wirt as a confederate of Adams, one of Jackson’s main opponents. Worse yet, Wirt had argued another case on behalf of Native American clients the year before Marshall’s ruling. In that case, which also reached the Supreme Court, Wirt was open in suggesting that Jackson could be impeached—should be impeached—if he chose not to execute a Court decision that ruled against the Jackson Administration. Jackson had threatened as much and he would never forgive Wirt for the strategy of what I might call “suggestive impeachment.”

You don’t need to be a fortune-teller to see Trump, like Jackson, injecting a large dose of the personal into this interaction with the judiciary in early 2017. He has already ridiculed the judge in Seattle—the “so-called judge” to use his words. Trump’s reaction was Jackson’s reaction. You can feel his blood beginning to boil.

It’s important for you to peel back a layer in our story. It occurs in the fourth year of Jackson’s first Administration. Marshall’s ruling—and Jackson’s reaction—is near the end of Jackson’s first presidential term with another presidential election only nine months away.

Here’s why I emphasize the year, 1832. By this point, the ill-will between Jackson and Marshall has spread throughout much of the judiciary across the United States. Jackson had antagonized many judges: “that barbarian Jackson,” said one judge; “a detestable, ignorant, reckless, vain, and malignant tyrant,” said a second; and “the nation is too young, though corrupt enough, for (his) destruction, May Heaven defend us!,” shuddered a third. After nearly four years of his presidency, acrimony raged between Jackson and judges. Four years. Mark that.

Where are we today? Well, less than a month. Not even four weeks into the Trump presidency and we see, hear, and feel tensions between the Executive and Judicial branches (yes, on city/state/regional levels). My point is that Jackson’s example tells of a strong likelihood for widening discord between the Executive and Judicial branches. The personalism of Trump, like the personalism of Jackson, will cause discord to spread, not to diminish. If things are at this level of tension in four weeks, the mind boggles at where we’ll be in four years.

Again, I think we can detect more trends to come if we look closely at Jackson’s example. For him, the executive/judicial acrimony had two effects, a pairing of the positive with the negative. On the negative side, it spurred the rise of a political opponent. William Wirt ran for the presidency in fall 1832 (and lost). On the positive side, Jackson maintained a high level of interest in the judiciary and took every opportunity to insert his allies into open judgeships. Ultimately, he named seven justices to the Supreme Court, including one of the most influential Chief Justices in American history, Roger Taney. Jackson recrafted the American judiciary into a fountain of Jacksonianism.

Which brings us to the final part of Jackson’s response to the Supreme Court ruling of March 3, 1832. A google search will produce a false-fact: Jackson was supposed to have muttered “now let Marshall enforce it,” according to a book written by a newspaper publisher more than thirty years after the event. Hardly any historians who write about Jackson give credence to the remark.

The truth, however, is more intriguing for our purpose of Jackson/Trump. Witnesses did state that Jackson expressed his belief that no one would be able to muster a single military unit to go to Georgia to enforce the Supreme Court ruling. To Jackson, such a ruling would need armed power if it were to overawe local resistance to implementation. That perspective would be proven true in the civil rights protests of the 1950s and 1960s.

Jackson didn’t press his anger against the Court. Jackson used behind-the-scenes communications to convince officials in Georgia to alter local rules and render Marshall’s ruling needless in the end. As things turned out, Jackson’s efforts in quiet collaboration with state and local officials in Georgia resulted in the removal of Native Americans (a heinous act, in any event) without challenging or violating Marshall’s ruling. Jackson embraced a more subtle path because, as circumstances unfolded, he had larger issues to sort out, an effort that would benefit from not furthering a national dispute in Georgia. (We’ll discuss this in a later post.)

So, this is where we’ll see if Trump continues to resemble Jackson in the dispute with judges and the judiciary. In his clash with the judges Jackson shifted from public to private, from overt to covert. He knew that dynamics on the ground—in the localities—would work in his favor. He continued to despise that group of opponents in the courts who, in turn, despised him. But he stepped aside from those animosities and pursued a different approach in his dealings during 1832 and 1833.

Will Trump? To me, the answer lies in his experience. That prompts the next choice: which experience would Trump use in his next actions with the judges? We’ll see what he chooses. For me, I’d suggest he look to his years as a builder and developer, not as an entertainer.

Action-Point: like the personalism of Jackson, the personalism of Trump will intensify the tensions with judges.

Next time: the reverberations of Obamacare from 1854 and the re-founding of the Republican Party—and Democratic Party—after 2017.