Leadership, Tea, and 1773

Those eyeglasses on your face are 250 years old. Can you see well through them? Take a look over there, where a group of people are dumping tea in Boston harbor in December 1773.

(for your leadership vision)

A swath of my Redux entries for 2023 have, one way or another, featured the oncoming story of the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773. I write my Redux from the perspective of people—famous and not-so-famous alike—who have no idea what’s coming the day after tomorrow. For them, as for you and me, the future is unknown. In that spirit I think you and I can gain value in finding timely leadership insights from the tea-related stories.

It may have been 250 years ago but in leadership lessons it’s about as fresh and familiar as this morning.

Below is my list of twelve lessons. I also provide beneath the list a brief description. If you’d like a fuller and more amplified discussion for yourself personally, please reach out to me via email dan@historicalsolutions or text 317-407-3687. We’ll arrange to talk. Thank you in advance for your time in reading and considering.

The List

- Extraordinary meaning can be found in an ordinary item.

- The effort to solve one problem can lead to the creation of a bigger problem.

- Don’t just communicate. Know the many ways in which communication functions.

- Distance separates in time and in space and in everything else.

- Polemics is a thing unto itself. Recognize where and when it belongs and where and when it doesn’t.

- Other issues are also happening. They can be affected, whether strengthened or weakened.

- The more obvious a prior example seems to be, the more inevitable the tendency to revert to it as the new, next step.

- Multiple and repeated—that’s what communication can require in the exchange between leader and follower. And embedded in this truth is the other truth—it can take time for that to happen as it needs to happen.

- Power appears in unusual places and forms.

- Action rests on a nest, web, and cradle of ideas.

- First things and final outcomes are far apart.

- Clarity in the finite can obstruct vision in the infinite.

* * * * * * *

1. Extraordinary meaning can be found in an ordinary item.

(the ordinary item of tea)

Dried tea formed into cakes. Cakes packed into boxes. Boxes stacked aboard ship. It doesn’t get much more ordinary than this.

And yet.

A group of people saw a deeply-held philosophy with complex principles in those dried leaves, boxes, and ship-holds. They saw freedom and liberty embodied and symbolized. They believed that the ordinary could be the first step toward greater losses and bigger threats. They were determined to assert their understanding of extraordinary stakes in ordinary moments.

Your leadership question: are you attuned to looking beyond the ordinary to find the extraordinary?

2. The effort to solve one problem can lead to the creation of a bigger problem.

(British East India Company logo)

A number of British members of Parliament and imperial officials believed they had a serious financial problem on their hands. That problem was the potential collapse of the British East India Company (BEIC), a quasi-public/private corporation with sprawling operations and engagements. It was seen, in later terminology, as “too-big-to-fail.” So, they developed two legislative acts—the Tea Act and the Governing Act—and guided them into passage with the sole aim of rebuilding the BEIC into a stable and successful enterprise. They didn’t realize, however, that provisions of the two laws produced enormous hostility in Britain’s American colonies.

Yes, it’s an illustration of the phrase “unintended consequences.” It’s more than that, too, I think. They had a greater role in creating the problems than in simply not knowing the unknowable. They were actively negligent, unimaginative, and lacking in curiosity.

Your leadership question: how much do you use your curiosity in anticipating an unexpected problem?

3. Don’t just communicate. Know the many ways in which communication functions.

(Alexander McDougall, or Hampden in his writings)

Communication cannot be exaggerated as a theme in the story of BEIC tea and the Boston Tea Party in 1773. Communication serves several functions and appears in numerous situations. The effective leaders in this story—such as Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Thomas Young, Jonathan Williams, Alexander McDougall, and Thomas Mifflin, to name a few—are those who excel in some aspect of communication. That’s really the key phrase here: “some aspect.”

Communication in the story of 1773 includes types (writing alone, speaking to a person or small group, speaking to a large group, writing as part of a group, and so on); settings (one-to-one, small-group private, large-group public, with an ally, with an antagonist, with the undecided); and nature of content (technical, strategic, abstract philosophical, inspirational, spiritual or metaphysical, and more). To simply say “communication” is saying almost nothing when it comes to the reality of leadership. You have to be precise in knowing the type, setting, and content of communication. In this story you see the good, the bad, and the both as leaders from the pro- and anti-tea sides grapple with the situation.

Your leadership question: which of the three—types, settings, and nature of content—do you instinctively know you need to improve?

4. Distance separates in time and in space and in everything else.

(the only way to cross the Atlantic Ocean)

This is one that tricks us. We look back and realize that it took four to eight weeks for everything (information, goods, people, germs, and so on) to travel one-way from Europe to America or America to Europe. So, for example, a speech given in Parliament that communicates a major decision will be known at the earliest in America roughly a month later. And the British colonists’ reaction to that decision will be known in Europe, again at the earliest, roughly a month after that. It’s an eight- to sixteen-week cycle at a minimum. Amazing to consider.

Our assumption is that such a story in such a world doesn’t apply to our age of instant, immediate communication. I think that’s wrong and wrong-headed.

The point here is distance and separation. More than time and space can separate us. Given the reality of our world right now, I think your best assumption on any sharing of information, news, and so forth should BEGIN with the belief that separation exists between you and someone else. That separation may be cultural, attitudinal, generational, or a hundred other things. It may be significant or it may not. But don’t simply assume that no separation exists in our world of instant, immediate communication. In some ways, our separations are bigger for us now than the Atlantic Ocean was for them in 1773.

Your leadership question: what separation do you see and experience on a regular basis?

5. Polemics are things unto themselves. Recognize when and where they belongs and when and where they don’t.

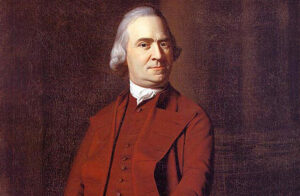

(Samuel Adams, polemicist as leader)

“A speech or piece of writing expressing a strongly critical attack on or controversial opinion about someone or something.” That’s the definition of polemics, a word you might not know automatically but which you see everywhere you look on your computer, phone, television, or (rarity of rarities) the printed page.

Polemical speeches and writings make for many sights and sounds in 1773. Samuel Adams is a master polemicist, to name a famous figure, but so are a host of other lesser-known people, including Thomas Young, Christopher Gadsen, Alexander McDougall, and Mercy Otis Warren. The words of these and countless other people in 1773 are worth knowing and remembering.

I think one thing that’s true is, now, everyone is polemical or, perhaps better said, has the opportunity to be polemical. We see polemics in almost everything, from politics to sports, from music to movies, from clothing styles to food choices. Social media, of course, has fed the fury.

We’re so oversaturated with polemics that we break into two camps—those who love polemics as makers or consumers, and those who hate it in any and every form.

The price of oversaturation is that we’ve destroyed the line between the right time and wrong time to use polemics and likely the right way and wrong way to be polemical as a leader. As happened with so many things, social media took an occasional necessity in life and blasted it into constancy and redundancy.

But yes, leaders do need to use polemics in particular situations and pivotal moments. We see the truth of it in Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Charleston, and two-dozen other places in late 1773.

The rub is the adjective and descriptor—which is “particular” and when is “pivotal”?

My answer is the one you don’t want to read—you’ll have to do the work and make the effort to know your sense of proper polemics in your leadership. If you don’t, you’ll never achieve the scale and depth of major change that we see in late 1773.

Your leadership question: are you comfortable as a participant in a polemical moment?

6. Other important issues are also happening. They can be affected, whether strengthened or weakened.

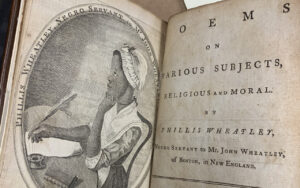

(Phillis Wheatley and her book)

This is powerful, a crucial finding in my Redux. I’ve found that two issues are occurring at the same time—one, the rising furor over tea and colonial rights AND, two, the early signs of an anti-slavery impulse and movement. The question will be how these two issues co-exist and interact. The same British ship that brought a load of tea to Boston harbor also brought the boxes of the first published book written by Phillis Wheatley, a black teenager who had been enslaved until a few weeks prior. It’s the perfect symbol for wondering how colonial rights and black emancipation will next unfold.

It will be difficult for both issues to remain dominant. As the story unfolds, the relationship between the two issues will change. The status quo between them will not last. One will rise and the other will…fall, shift, connect with, or something else. The point here is that they will change in relation to each other and something will drive the change. In the case of 1773, my research shows that the more colonial rights becomes a coastal/continental phenomenon, the greater the instability of the connection between colonial rights on one hand and emancipation on the other.

Your leadership question: when that big issue strikes you and your followers, how will you know if a second issue is right beside it?

7. The more obvious a prior example seems to be, the more inevitable the tendency to revert to it as the next, new step.

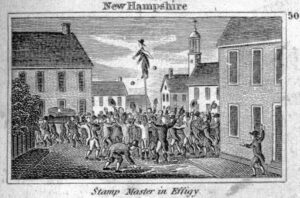

(Stamp Act protestors hang an effigy in 1765)

Eight years before the Tea and Governing Acts and Boston Tea Party of 1773, the Stamp Act of 1765 had torn apart British imperial and colonial relations. A colonial rights movement immediately bubbled up. The movement’s supporters organized protests (some of which became riots), formed an economic boycott, forced a handful of imperial officers to resign, and applied intense political pressure on British policymakers back in London. They succeeded—Parliament repealed the Stamp Act several months later.

Fast-forward to the fall and winter of 1773 and you see colonial rights’ supporters repeating the same strategy. They expect the same positive outcome. However, things have changed. It doesn’t take long for the template of eight years prior to take a different direction. The consequences quickly become different as well. The upshot is that what was expected to be a replay turned into something unanticipated and with even bigger stakes and implications—and risks—than before. There’s your lesson—you can attempt to repeat a successful strategy but the next outcome can unfold much differently than planned.

Your leadership question: when do you know that a tried-and-true strategy won’t work in the same way in a future application?

8. Multiple and repeated—that’s what communication can require in the exchange between leader and follower. And embedded in this truth is the other truth—it can take time for that to happen as it needs to happen.

(Old South Meeting House, site of multiple meetings and repeated messages in 1773)

Many of the arguments made in the speeches and writings of colonial rights’ leaders were not new. They may have been heard in a moment earlier in the fall or winter of 1773, at another rally or meeting or in another newspaper essay. They may also have been heard or seen in 1765 with the Stamp Act crisis. They could have been echoes from much earlier episodes in European history, such as the Magna Carta of 1215.

Repetition can be good. Repetition makes the point. Communication of your most important point, be it a vision, strategy, plan, or simply the next clear step of execution may need repeating. You can’t express it once or twice or even three times; you might need to repeat it over and over. You may think that such repetition wears thin or is mind-numbing to your followers. Be forewarned—repetition may be utterly necessary if the message is to sink in, to be absorbed so deeply as to allow for swift, confident, and immediate action. Do you get bored with your own repeated communication? Too bad (say I with a smile). Take a breath and say or write it again.

Your leadership question: is it my instinct and preference to want to move on to the next thing in my communication?

9. Power and influence appear in unusual places and forms.

(in honor of Nathan Hale)

18-year old Nathan Hale, a British colonist in Connecticut, had just started his first real job in late 1773. He was a teacher with his first assignment in a one-room school; Hale was also a fervent supporter of colonial rights. On that opening day of his teaching career Hale met with his students and launched into his first lesson from the front of the classroom. He had no idea that in the very near future he would volunteer to fight for colonial rights and then for American independence. In that spirit he would show an unusual willingness to take risks. That risk-taking spirit impressed one of his heroes, General Israel Putnam. Hale became a leader among Putnam’s infantry, causing him to seek a promotion into a new kind of military service, the spy. Teacher turned soldier, soldier became leader, and leader offered his life in the service of his country.

You can’t rely on the conventional stuff to determine who has power and influence. These do not only come from formal authority, from the outward appearance, the known background, or the expected pathway. The origins and sources of leadership will often surprise you, especially in those times of crisis and challenge. And that goes for you, too—don’t assume that your past prevents you from showing genuine leadership in the present and, likewise, don’t assume that your past guarantees your emergence as a real leader.

Your leadership question: are you ready to rise to the occasion regardless of who you are?And are you ready to accept someone else doing the same?

10. Action rests on a nest, web, and cradle of ideas.

(first English edition of Aristotle’s Politics, available for your use at The Remnant Trust in Indianapolis)

When you take the time to read the public speeches and printed essays in the controversy in late 1773, you see very quickly that leaders like Alexander McDougall, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams are building on ideas and principles that are decades-old, even centuries-old in some cases. Yes, they’re placing these ideas of freedom, liberty, property, security, consent, and more in a new context—in their context—but the truth is that they’re drawing on philosophers and commentators that go back nearly two thousand years. Aristotle, Cicero, Seneca, Paul, and Augustine, to name five, inform thinking and rhetoric up and down the Atlantic Coast in late 1773.

You need to know the sources of your values, principles, and ideas. Such self-knowledge will strengthen your resilience in the situations when you need it the most. You can gain confidence and steadiness from an awareness of time-tested and life-proven philosophies and world-views. And though it’s not popular to say it in these terms, your insight and clarity of the roots of your thoughts will take you a long step closer to something we all seek, or should seek—wisdom. And if anything seems in short supply these days, it’s wisdom.

Your leadership question: can I trace a path between my beliefs and ideals to an earlier source? Am I confident that my sources have been tested?

11. First things and final outcomes are far apart.

(a leader will sometimes be alone)

As I mentioned before in Point #7, colonial rights leaders are confident that the playbook of 1765 can be used again in late 1773. This confidence narrows their planning and visioning. They don’t take the time and don’t use the imagination to consider that they might be on a new, unknown path. Under the pressure of daily challenges, perhaps it’s too much to expect them to have done so.

Nevertheless, a price will be paid for not having attempted to think through more than the next step. They weren’t ready for the severe weight put upon their assumptions about the virtues of citizens or the common-good known and shared by most people. The reality of life didn’t make that mistake—quite the opposite, in fact—because life was quick to prove that people weren’t as virtuous as expected and the common-good looked uncommonly different to different people. There was boldness and courage in the moment. There was disappointment, sacrifice, and shock in the future. After late 1773, much more was to hang in the balance than was originally believed.

This isn’t to say that they couldn’t or wouldn’t ultimately triumph. Not at all. But it is to say that triumph made demands far beyond the next month, the next quarter, the next year, or years. In the span and crucible of such times, lonely is the leader.

Your leadership question: what do I fall back on when I’m faced with the long haul and the long run?

12. Clarity in the finite can obstruct vision in the infinite.

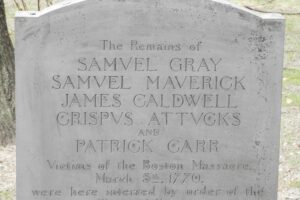

(grave of black protestor, Crispus Attucks, killed during the Boston massacre in 1770)

Freedom and liberty, these were the watchwords on many lips in late 1773. They were spoken and written with sincerity and genuineness. And with clarity. However, you didn’t have to look far to see that only some people meant these words for every person. People continued to be enslaved, the vast majority of whom were African in birth or descent. People continued to be driven off their lands, the vast majority of whom were Native American. People continued to be regarded as having half-rights in a sense, the vast majority of whom were women, the indigent, the very young. Many people who asserted their right to freedom and liberty lacked the vision to see the scope of such rights across their lives and world. In pursuing freedom and liberty, they as individuals denied the same to other people as groups. Notably, they weren’t the first to suffer from such a lack of vision and they won’t be the last. This fact of life does not absolve one’s duty to test one’s own sight for true vision to ensure, as has been said and written, that our eyes are not covered with scales. We have the potential to see clearly in others what we wish to see in ourselves.

Your leadership question: does my clarity of vision reduce the range of my sight?

Thank you for reading and again, if you wish to discuss more in depth, feel free to reach out to me at 317-407-3687 or email dan@historicalsolutions.com

(Your Future, or The River ahead)