Ariana and Abraham. Grande and Lincoln. A warm June night in Manchester, England, UK. A cold November day in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, USA. Three hours in 2017 and three minutes in 1863. A universe apart.

Across such a span, is there anything they can say to one another? I’ve thought about this question for more than a year. I’ve searched the span and I think the answer is yes. They can speak to one another. And in the particles of life that drift and flash from time to time, what might be said between them might also be said between us.

Give me ten minutes so we can watch for signs in the dark night.

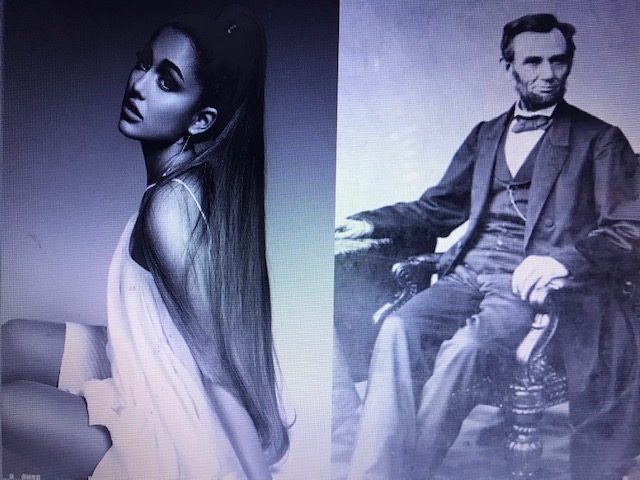

The differences dominate the view. He’s an older white guy, a politician, born in backwoods Kentucky just a decade after the death of his idol, George Washington. She’s a vivacious young Italian-American woman, a pop music singer, born in glam South Florida just ten years after her idol, Whitney Houston, debuted on national television. The best-known images of him feature a rail-splitting ax, scraggly beard, and the wrinkles of time and torment. The best-known images of her feature a pair of fuzzy pink cat ears, long hair pulled back in a ponytail, the picture of youth, all style and beauty. He’s an icon of American history. She’s an icon of American, and global, pop and stan culture. Then there’s the 150-plus years separating them. So great are the differences that it’s hard to see anything else.

We need a lens to sharpen our focus and peer deeper into the black.

In 1863 violence brought Lincoln to eastern Pennsylvania for the first time. Months before, the largest battle of the American Civil War had raged at and near Cemetery Hill where, now, he was part of a dedication of a military graveyard. In 2017 violence brought Grande to Manchester, England for the second time. Days before, one of the largest bombings in peacetime Britain had torn through a crowd leaving her previous concert at Manchester Stadium where, now, she was doing a show in honor of victims and survivors.

These two people, Lincoln and Grande, took on the task of trying to make sense of tragedy, of tracing a meaning on a surface stained with blood. They were famous participants in an organized memorial event.

Lincoln saw his memorial purpose as understanding. He sought to help the people of his nation understand recent human loss unthinkable in scale, 23,000 dead or wounded or missing. He was their president and the war was dragging on and on and on. At first, he and they wanted to hold the nation together. Then, now, he and they—or at least more of them than before—realized that maintaining the union had to include freedom for those denied it since the founding. Lincoln came to Cemetery Hill to be among soldiers who had fought and were yet to fight, among citizens in support of fighting or opposed to fighting, among communities drenched in war and of a world that knew a war was raging.

Grande saw her memorial purpose as coping. She wanted to help the people of a city and the followers of her music cope with recent human loss inconceivable in thought, more than 300 injured or killed. She was a performer who attracted fans from around the world, people who enjoyed her songs, dances, fashion, friendships, and relationships. She and they loved a life of innocence, happiness, mutual interests and enjoyments while hoping others did the same. She came back to Manchester Stadium to be among people determined to show that fighting would not be condoned though others still craved to kill, that violence would not be accepted though others aimed to fight, that war would not be thrust into their midst though others plotted to do so.

They prepared. Lincoln spent pieces of time getting ready. An hour here and there, likely also during his train ride to Cemetery Hill, Lincoln recalled his experience over the past year, speeches, the speeches of others, such writings as the Bible, and new thoughts in his own head. From them he scratched out not quite 300 words onto stiff writing paper.

Grande spent time similar to Lincoln. Like him, she recalled. In her case the recollection was of recorded songs and stage routines. More than him, though, the recollection involved longer repetitions of lyrics and rhythms that had been frequently rehearsed. She would also rely upon what she’d heard from others as well as her own very new reactions. She had far more time to account for in her memorial than Lincoln did.

Planning preceded them. Other people scheduled and arranged and organized. Specific people—Republican activist David Wills in 1863 and Live Nation concert promoters Melvin Benn, Scooter Braun, and Simon Moran in 2017—got the project done, ensuring the participation of performers (public speakers and singers), the assembling of stages, and the laying out of security. The behavior of masses, visual lines of sight, and the ability to be heard in the distance were issues to be considered and resolved.

Cemetery Hill and Manchester Stadium contained crowds. Upwards of fifteen thousand people were at Cemetery Hill, overwhelming the local population by a multiplier of five. Crowds of this size rarely existed in the everyday experience of attendees. Simply being there was remarkable to them. They stood and strained to see and hear those people on the platform. Most of them heard little or nothing in detail. Until newspaper reporters filed their stories or observers closer to the speakers’ platform re-told their view of the day, few would know fully about how the event actually happened.

Fifty-five thousand people crammed Manchester Stadium, a tenth the city’s population and a common scene in major sports and entertainment facilities. They heard and saw it all, every pulsation, every beat, every shout and whisper from the stage via a massive audio speaker system. In addition, they saw every movement and gesture via an equally massive video screen. And they were able to transmit sounds and pictures via smartphones to people around the globe, just as various communication networks were doing via satellites.

With the technology and numbers of people, we’re tempted here to relegate 1863 and 2017 to different universes. Look again through the lens. Key details appear.

Cemetery Hill wasn’t pre-technology. Like Manchester Stadium, Cemetery Hill had new and emerging technologies that were affecting people in ways they dimly grasped. The railroad helped make the event a reality for Lincoln and hundreds like him. People traveled distances they otherwise couldn’t have traversed; military strategists in the war itself didn’t yet understand the impact of trains. Reporters covering the event at Cemetery Hill would send articles to editors via the telegraph, a nearly instantaneous “wired” acceleration of information nonexistent a few years before. Finally, if people stood still for several seconds, skilled specialists could freeze the scene on glass plates for reproduction and distribution. The popularity of photographs would produce new habits, practices, and, ultimately, laws, regulations, and judicial rulings.” Combine the newness of railroad, telegraph, and photograph, set it alongside the crowd’s outlook of “back before all these new things arrived”, and suddenly the people of Cemetery Hill encircled by life-changing technologies just like the people of Manchester Stadium.

The events of Cemetery Hill and Manchester Stadium started in similar ways. At Cemetery Hill, a German musical band from Philadelphia played special music, somber in tone, written for the day. No words were spoken. Then, Chaplain Thomas Stockton read a prayer he’d penned for the occasion. Praying with poet-like eloquence, Stockton called for gratefulness to God that His soldiers “took their stand upon the rocks” and repelled a slaveholding enemy. At Manchester Stadium, a moment of silence marked the start of the event. Then, poet Tony Walsh read his rhymes about Manchester’s history of greatness and resilience because “there’s hard times again in the streets of our city.”

With the start complete, the events continued with a mixture of songs and remarks. At Cemetery Hill formal speeches were the primary method of communication. Music was secondary, though one song was composed especially for the moment: “Oh Father save, a people’s freedom from the grave,” went the lyrics by Benjamin French. A choir from nearby, the Baltimore Glee Club, sang.

In Manchester Stadium the reverse was true; songs were dominant while spoken remarks were secondary, scattered, and informal. There were exceptions, as two people read from prepared texts and videos played with brief statements by performers elsewhere who couldn’t be in attendance: “Don’t go forward in anger,” read co-producer Scooter Braun from words glowing on his smartphone, “love spreads.” A choir from nearby, the Parrs Wood school choir, sang.

Ariana Grande cast a longer shadow on her event than Lincoln did on his. She was a headliner, famed throughout the world and the focal point of millions watching. He was an afterthought at Gettysburg, tacked on by schedulers to “give a few remarks.” Popular orator Edward Everett was the keynote speaker on Cemetery Hill and the fact that this was the first open day on Everett’s busy calendar was why the event was held late in the fall. Everett rooted his speech on details of the battle and the larger influences of Christian and classical thinking. Having memorized his text, he spoke effortlessly for almost two hours.

Grande had other advantages over Lincoln. She attracted the help and support of dozens of other performers who were friends, acquaintances, or simply wanted to be part of the memorial show. Grande further had a greater opportunity than Lincoln to shape the event. She determined the order of appearance and choice of song, essentially a fourth co-producer. And it was Grande, not Lincoln, with the global reputation. People in forty nations across the planet were aware of the event as it happened and even more likely knew at least some of the details of the bombing attacks. They knew many details of her life, as well.

Yet, unknown to Grande, she walked in Lincoln’s bootprints. He rehearsed his performance immediately prior to the event. So did she. He added to his approach at the last minute. So did she—Lincoln finished his speech the night before the ceremony and inserted notations on the speaker’s platform before standing up to speak, while Grande met with a victim’s mother and decided the day before the concert to scrap the planned song list in favor of what the deceased daughter would have wanted: “to hear the hits.” He visited sites associated with the events to learn more about what had happened. So did she—Lincoln had a private tour of the battlefield while Grande had a private meeting with victims’ families.

But what about their messages? What about the meanings they contained?

Lincoln found meaning in the soldiers and their choices. They were warriors in a struggle to defend an idea that defined a place. The idea—or “proposition”, as he phrased it—was self-government formed around equality of existence, the place was the United States. The value of the idea and the place was revealed in the sacrifice of those who had died, those who still served, and the people of the place at war with themselves.

Grande found meaning from civilians with no choosing of a conflict. They were guiltless innocents whose actual choice was deciding to attend an experience of entertainment. More than that, they were leaving from a place of pleasure to return home, the other place in their lives associated with security, safety, and support. It was there that the bomber had intervened and turned their choice of happiness to the chance of death.

Lincoln and Grande agreed on the need to honor and remember. Lincoln reminded the crowd on Cemetery Hill that they had assembled to dedicate part of the battlefield as a burial ground for the dead—”it is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.” Thousands of people held up signs at Grande’s show that read “For Our Angels.” Many cried as they held the signs above their heads and music filled the air. Grande wrapped her arms around a young girl on stage who, while singing the song “My Everything”, struggled to hold back tears. The crowd struggled, too.

Lincoln would have understood these tears. So would a man within hearing distance of Lincoln on the platform at Cemetery Hill. He wore a blue officer’s coat with one sleeve dangling at his side, a survivor of a wartime amputation. During Lincoln’s remarks on the speakers’ platform, the one-armed man began to cry. Seconds later, he convulsed in uncontrollable weeping and covered his face with his one remaining hand. He was trying to control himself. But a minute more and his strength collapsed—he pulled his hand back from his eyes and yelled in full voice, “God Almighty bless Abraham Lincoln!” The One-Armed Man would have felt at home in Manchester Stadium, holding his Angel sign, singing a Grande song, and crying his heart out. With his empty blue sleeve.

Lincoln offered a confession on the crowd’s behalf. As their spokesman, he admitted that “the world will little note nor long remember what we say here.” We have, Lincoln said, a “poor power to add or detract.” He went further and specified more—nothing that is said today at this event will live long, no one will remember us. Lincoln was targeting now the people on the platform, those who were speaking or singing or praying, people like himself, those expected to express to others.

Lincoln paired this confession with a declaration. He declared that the people who would in fact be long remembered, long honored, long cherished—the true heros—were those who had done things here, the soldiers struck down in the horrific battle and never to rise again.

Perhaps it was here that the One-Armed Man had broken down.

Lincoln offered action as crowd spokesman. He told the crowd—the living, as he chose to call them—to finish the work, maintain their resolve, and always uplift the service of the dead. There was a union to be made endurable and an expansion of its freedom that had been too long refused. The dead were still doing, Lincoln suggested, because their memory could and should be kept alive as examples for the living. The power of their doing would be all the greater when the people brought a rebirthing to its natural life. This the people must do if they hoped to remain seen among the places in the world.

Grande and her friends embraced Lincoln’s words about “what they did here.” They paid tribute to the dead and wounded from the bombing attack. In addition, Grande repeatedly thanked the crowd that attended the benefit concert. Their action both honored the suffering and announced they would not be deterred from the future loves and joys of living. Miley Cyrus told the audience of her love of their city and fondness for appearing there, of sharing in who they were. Sting, in a video broadcast, talked about “remembering those who suffered…(and) celebrating the spirit of this great city.” Robbie Williams changed one of his songs to include a chant of “Manchester, we’re strong….” 55,000 people repeated the words, with thousands of them wiping tears as they sang.

Grande and her friends followed Lincoln along an altered path of their own. Their event was a form of nonviolent fighting back, a non-national collection of people waging a celebration battle, a Grande scene of the grander cause. This cause was not of a place but of attitudes, outlooks, and ways of living across many places. Performers and audience alike reminded each other of actions and beliefs they insisted must and would outlast their attackers. They expressed their commitment to “love,” “acceptance,” “mutual respect,” and “openness.” Canadian singer Justin Bieber said, “You guys are so brave. What an amazing thing we’re doing tonight, would you not agree? Would you agree that love always wins?” As Lincoln had done, and purposely not done, they spoke hardly at all about an enemy and more about each other and the ties that bound them—reinforcing an approach as mutual participants in community of a lifestyle.

The manner of life and living praised at Manchester Stadium was possible in part because of the place and ideas expressed at Cemetery Hill. Lincoln’s emphasis on people grounded in freedom and governing in equality opened the door for subsequent values and principles to flourish, including those at Manchester Stadium. Lincoln’s vision clashed with the brutish impulses of an enemy sworn to uphold a darker society and system. He grappled with the foe of his world while, later, Grande and her friends confronted another threatening adversary in their world. Words from Cemetery Hill echoed in the songs of Manchester Stadium.

A sense of religious spirit sustained them at Cemetery Hill and Manchester Stadium. Surrounded by all the features of a defined Christian service, Lincoln used a Biblical formula for describing the age of the United States, emphasized the nation’s position under God, and spoke of a second birth, being born again. At Grande’s concert, beyond the appearance of “Angels” on every sign suspended overhead in the audience, Justin Bieber was explicit in saying: “…God is in the midst. He loves you. He is here for you.” The words of Grande’s friend brought more tears, more Angels in flight. Grande sang and spoke in tones that hinted of the victims having “gone on” to some better place. She captured this feeling when performing with her friends the event’s finale, “Somewhere Over The Rainbow.”

With a strange irony, the song served as an invisible bridge between 1863 and 2017. Grande’s grandfather, Frank Grande, had loved the song. It was his favorite. Ariana had chosen to sing the song to him while he was dying, among the last words he heard from his granddaughter before death. The song was written in 1939, when Frank Grande was fifteen years old. Ironically, 1939 was the same year a man named William Rathvon had died. Rathvon was the last living eyewitness to Lincoln’s words on Cemetery Hill. In the spirit of Grande’s encore, they were all now above the problems of the world, beyond the sky, somewhere, joined by the soldiers of 1863 and the civilians of 2017.

The two memorial events weighed down on Lincoln and Grande. Abraham Lincoln left Cemetary Hill and on the train ride back to the White House fell ill with a mild form of smallpox. The war waited for him, as did his presidency. Ariana Grande suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition from which she is still slowly emerging. The sudden violence of a different sort of war waited, too, as did her career.

The events of Cemetery Hill and Manchester Stadium were rapids in the River of Time. Events fixed in the past, they fell further and further behind the present. They were memory subject to the tensions of remembrance and forgottenness.

In the early River, the first days, after Cemetery Hill political partisans on both sides seized upon the speech for a short while. Supporters loved it, opponents hated it. Then—vanished, except for one or two private recollections, as when Edward Everett wrote and asked Lincoln for a written copy of the speech. Two years further Down River, with Lincoln’s own murder, the Cemetery Hill event was recalled once more. Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner delivered a eulogy of Lincoln that fixed the three minutes of Cemetery Hill in the center of Lincoln’s wartime presidency. But again, public attention faded thereafter.

More water, Down River, further on. Another decade or so passed before people remembered Lincoln’s three minutes on Cemetery Hill. A railroad company publicized remembrances of the event as a way to generate ticket sales for ridership. By the 1890s, as 30th-anniversary occasions were organized, Lincoln’s speech began to enter more formally into American historical consciousness. Reprintings of his speech became the norm. A fictionalized painting of the scene was done. Aaron Copeland composed a symphony that partly rested on the speech. The rest was the history most of us know, especially as textual speech readings and performances of Copeland’s music in July 4th celebrations.

Though we may feel differently in our daily lives, only a little time has passed since Grande’s event. It’s early on the River; the Manchester memorial of 2017 is fresh memory. Recall came quickly in the one-year anniversary in 2018, an event marked by the British Prime Minister and some of the royal family. Part of the memory is Grande’s personal remembrances, unlike Lincoln. Her remembrances consist of attempting to cope with her PTSD, the placement of a tattoo of a bee—the Manchester city mascot—behind one of her ears, and efforts to join in the Manchester Pride tribute in 2019. Every person affected by and involved with the original bombing scene and the subsequent memorial will have, like Grande, flash-backs, dreams, nightmares, evolving mental images. They will tend their memory storehouse as many people at Cemetery Hill did in the unfolding months and years.

You may have noticed that the Manchester memorial didn’t include a speech or set of remarks from Grande. She hugged and gestured, and spoke in short phrases between songs and displayed the rawest of emotions without speaking formally. She didn’t offer her three-minutes of thoughts like Lincoln.

Then, it happened.

In the period of emerging memory after the finished memorial, Grande offered her thoughts in a more complete fashion. She wrote a public letter eight months on, her equivalent to Lincoln’s “few remarks” on Cemetery Hill. It was as if her Gettysburg Address could only come when she was more emotionally in control than on the night of the Manchester Stadium memorial; it’s understandable when you recall Lincoln was not at all involved in the actual Battle of Gettysburg. Grande had been on the scene of the original bombing and was there again for the nonviolent counterstatement of the memorial. Her speech at Cemetery Hill may have been a public action to release grief, to ease pressure.

Grande wrote, “(the bombing) will leave me speechless and filled with questions for the rest of my life.” She stated that music was supposed to be safe, as it had always been for her. Music’s purpose is to join people together in a spirit of fun and happiness. The introduction of the fullest opposite of this reality was “shocking and heartbreaking in a way that seems impossible to fully recover from.” She praised the people of Manchester for helping her and her friends and colleagues how to persevere. Through their example, it was clear that hate had lost, love had won, and an event was changed from “the worst of humanity into one that portrayed the most beautiful of humanity.”

The faintest touch of Lincoln. I’ll bet he would have been proud of her as a daughter. If you believe in the spirits of Cemetery Hill and Manchester Stadium, you’ll wonder for a moment if Grandfather Grande has met Founding Father Lincoln.

To predict some of memory’s future, we can find insights for Manchester Stadium from Cemetery Hill. A later tragedy, Lincoln’s death, helped keep the memory alive in the words of a eulogist. Indeed, so tightly was the binding between the death and the speech that in time they couldn’t be separated. Anniversaries gave power to remembering, too, especially in the significant numbers of 25th, 30th, 50th, and so on. But the strongest restoration came with the tides of larger events. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the onset of intense immigration and involvement in overseas wars drove Americans to seeking to know more of who and what they were as citizens and a nation. Added to this turning, churning wheel was the decision to ignore or disregard other aspects of other events within the remembered period. The Cemetery Hill speech was less controversial than whether or not racial equality had been achieved through the war and its battles. The desire to maintain the memory of Cemetery Hill was all the more attractive when uglier parts of the Civil War weren’t resolved. Tragedy and pain became easier to understand than hope or promises.

For those of you who made it this far in my essay, I thank you. Truly. I know your time is valuable and I’m grateful you’ve spent some of it with me. Before we part, I’d like to add two wishes—one could be fulfilled, the other can never be.

The first is for Ariana Grande. I wish that she will be able to read about Lincoln and, above all, his mental journey—his River—from the short speech on Cemetery Hill in November 1863 to the shortest (and most powerful) inauguration speech in American history in March 1865. She might just find a few of the answers she’s looking for.

The second wish is for Abraham Lincoln and, hence, its unfulfillment. I wish he could have done what she did. Take the time several months after an important event, look back on it, and write down your thoughts and feelings since, standing here, at this later point. And then, still further Down River, do it again. That would have been quite a document. Now that I think about it, maybe that’s what Lincoln did in the Second Inaugural Address. Well what do you know…

Ariana and Abraham. They have a bond, after all, made in memory.

Thanks for reading. All the best, Dan

(p.s. in honor of Cemetery Hill, find Lincoln’s remarks and read them–let me know what you think)

(p.s.s. our youngest daughter Ava is a huge fan of Grande’s and, in her words, “I think she is very inspiring”; also, she likes Lincoln, too)