This is a FREE leadership exercise. I invite you to use it. And when you’re done, I invite you to reach out to me for a FREE second step (more about that below).

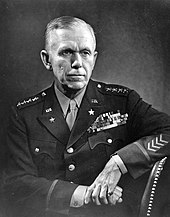

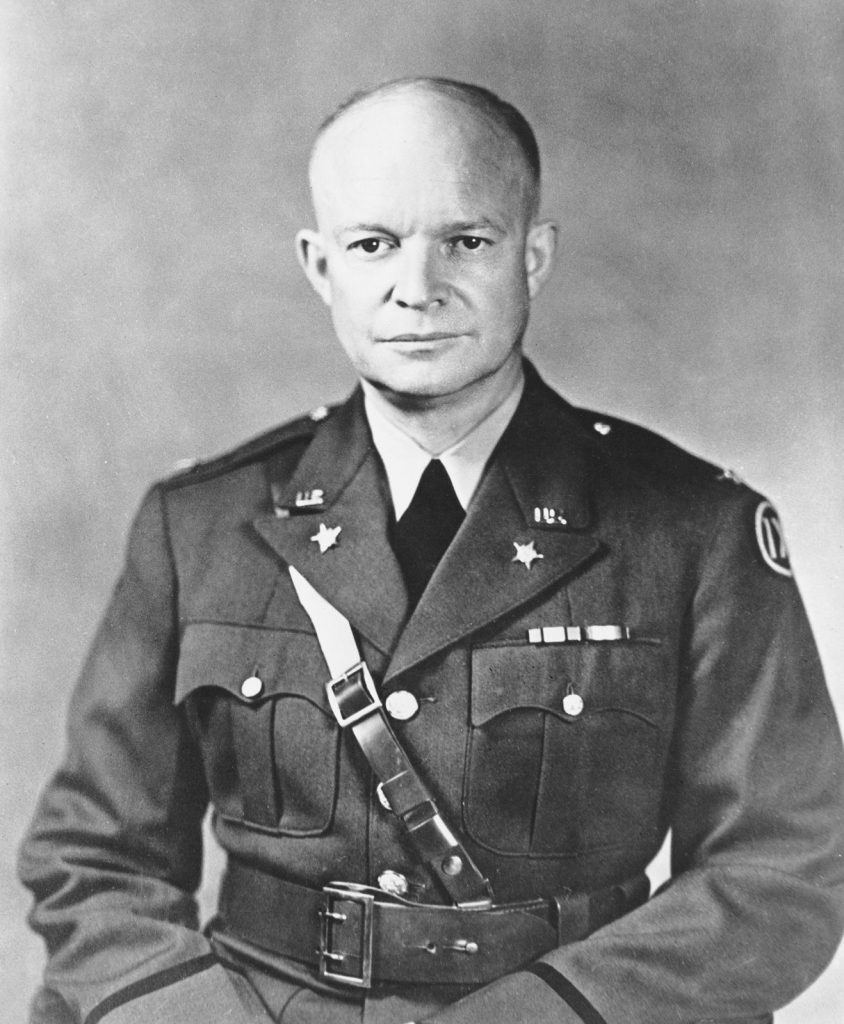

Our topic is leadership and communication, though as you’ll see, it’s really a lot more than that. You’ll move through Brigadier General Dwight Eisenhower’s experience of his first significant meeting with Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall at an especially critical moment. I’m pleased to be your guide.

I recommend you read these stories, these seven brief Pieces, in their proper numerical sequence. You’ll see that from time to time I pose questions for you to consider. Finally, when you’re done with the 7-Piece sequence, I invite you further to reach out to me if you’d like to talk about them. Our conversation will be free (yes, again) and entirely confidential. Our private chat will be a great way for you to know how to apply what you’ve just done. You can email me at dan@historicalsolutions.com to indicate your interest in such a conversation. We’ll schedule it from there.

Here we go.

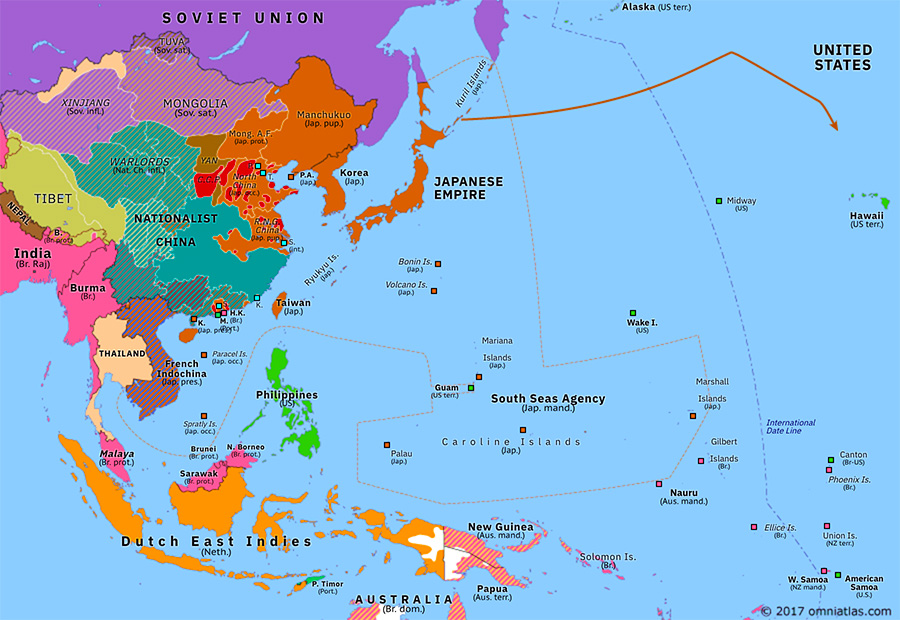

It is Sunday afternoon, December 14, 1941, one week after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Territory of the United States. Just days before, the US had declared war on Japan, Germany and Italy declared war on the US, and the US declared war on Germany and Italy.

The world is on fire and the United States is now formally fighting World War Two.

Piece #1

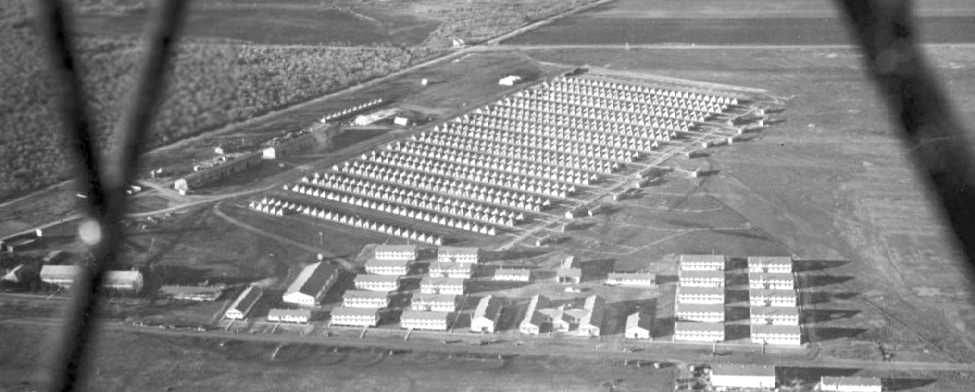

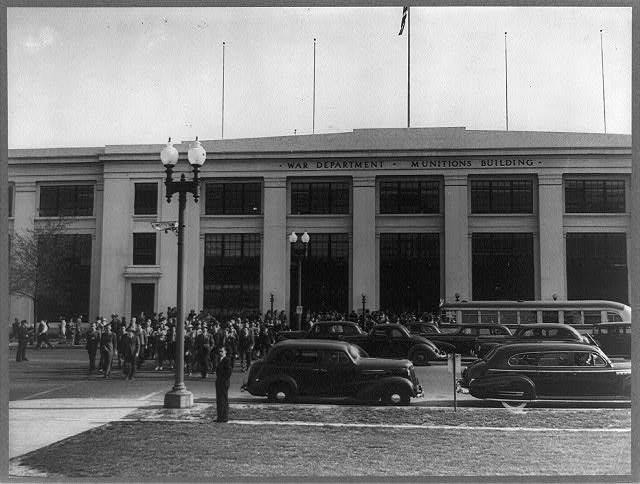

This is an airfield at Fort Sam Houston in Texas. On Friday, December 12, 1941 Brigadier Dwight Eisenhower boards a flight to travel from here to Washington DC. He knows he is entering the War Plans Division in the War Department in some capacity. It will be his new job. In the past week since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States has formally entered World War Two, allied with Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union against Germany, Japan, and Italy.

My questions to you:

- What should he use the time on the flight to think about?

- What should he absolutely not think about at all?

- What’s been your most important space as a leader this week?

Piece #2

Over Saturday in Washington DC, Eisenhower settles in. Several years before he had worked as a lower-ranking officer here. By Sunday, December 14, he is in his new office at the War Departmwent. His new office space is plain, ordinary, and well out of the way of the flow of things. In other words, he’s clearly nothing special in this new assigment in the War Plans Division.

My questions to you now:

- In this new space of his office, the first time in really being there, what do you do if you’re Eisenhower?

- Is this a time for further thought and thinking? If not, then what is this time for?

- How different is this space from the plane?

- Do you prefer for a certain amount of time to pass when you’re “settling in”?

Piece #3

As you sit in your office on Sunday, December 14, settling into your new surroundings, a black telephone rings on your desk. You answer it. On the other end a voice says: “The General wants to see you right now.” In the War Department on this day there are dozens of generals to be found. However, there is only one person called “The General” (the “The” is the big thing). He runs the place—US Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall. He’s the boss and your boss. You’ve worked for him, technically, for about twelve hours. And he wants to see you as his new Director of the War Plans Division. Before now, over the past couple of years, the two of you have met three times for a grand total of perhaps fifteen minutes. By the way, Marshall’s hiring of you and his elevation of you occurred because of two things—he knows and respects your former boss, who gave you a fabulous recommendation; and he knows about some of your performance in a newly designed and first-of-its-kind training exercise (the Louisiana Maneuvers, back in the summer). And so now, you walk the halls and head towards The General’s office. You are fully aware of the magnitude of this moment. This is the meeting, just minutes away, a sort of opening scene to the new life you flew to begin in Washington DC.

My questions to you:

- How do you want to conduct yourself in this meeting?

- What do you expect from your new boss in this meeting?

- For yourself personally, what do you want to be true the next time you have a truly “big” meeting with someone?

- What’s your favored way of communicating in a “big” meeting?

Piece #4

You enter Marshall’s office. It’s almost as nondescript as your office. Marshall signals for you to sit down. No salute. No small talk. No chit-chat. No can-I-get-you-a-cup-of-coffee. Nothing except he stares straight at you and then starts to talk in a deep voice. He describes how bad things are militarily for the US right now in the Pacific. Lists six or seven things. Then, ending his description, Marshall stops. Still looking straight at you, he says, “What do you think we should do?” And then, he’s silent. He’s waiting for you to answer. This is the complete extent of the beginning of the meeting, arguably, the most important person in the American military at the moment and the person newly hired to his team.

My questions for you:

- How many seconds do you have before you respond? Count them out and see how it feels to imagine the silence and the waiting.

- Is your answer a make-or-break kind of thing?

- What are the implications of your answer?

- How do you interpret Marshall’s question?

Piece #5

Meeting Marshall’s gaze with his own, Eisenhower requires all of about three seconds to reply.

He states: “Give me a few hours.”

Marshall: “All right.”

Eisenhower leaves Marshall’s office and returns to his own office space, where he begins working on the future that awaits at the end of a few hours.

My questions for you:

- What are the implications of Eisenhower’s answer?

- What has to be true for this 1/1 exchange to have occurred?

- How different is it if he asks for a “few minutes” instead of a “few hours?”

(Before we go on, I want to share one of my deepest beliefs with you. It’s choice. The choices around us are everywhere. We have far more choices than we ever suppose. It’s true, too, for this remarkable moment between Eisenhower and Marshall. Either person can choose to do or say or gesture in any of a hundred ways. Neither one of them has a script. Neither one of them knows what exactly will happen, unlike you and I who can read what happened. Choice—never forget it. Thanks for indulging my digression.)

Piece #6

After three hours, Eisenhower returns to Marshall’s office. He tells the result of his work. Essentially, he suggests using Australia as the US base for further action in the Pacific in the next twelve months. Marshall listens and then reacts—he tells Eisenhower that everyone in the War Department tends to only bring problems to him; they then expect him to have the solution. He goes on to say that he wants the problem, the solution, and an update on progress thus far, all of them together. That’s what Marshall says he wants. By inference, then, Marshall communicates that Eisenhower has handled this exchange effectively. And thus, for Marshall, meeting over and meeting adjourned. (Get here early tomorrow, Eisenhower.)

My questions for you:

- What has to be true for Marshall to expect his team to do the three things he lays out here?

- How many members of your team, right now, are ready to do these three things?

- Remember something about what actually happened next in 1942—US President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill meet in secret and agree that Europe and the Atlantic, not Asia and the Pacific, will be the first and primary focus of Allied war efforts. Eisenhower’s suggestion about Australia is not even a month old and it’s become a non-starter; he can’t even know or realize it yet. He will immediately have to pivot despite his personal belief and the fact that much of his recent military experience has been in the Pacific. So, here’s the question—what do you rely on in making the pivot?

Piece #7

Leaving the meeting and the War Department that day, Eisenhower reflects on what’s just happened. He tells himself that, going forward, he knows he should only involve the boss when one of two things is true–either the boss expects to be involved or the boss needs to be involved. Otherwise, Eisenhower concludes, he gets things done without further action from his boss. And tomorrow is Monday.

My question for you:

- Does having a boss like Marshall make it harder or easier?

- If you’re Eisenhower, what’s the most important thing to remember when communicating with Marshall as your new job unfolds?

In conclusion…

My clients know that I think of time as a River. Like a River, time flows in one direction—ahead and forward of where it was one second and one inch ago. Time acts the same way. That’s why I think the River makes an excellent analogy in understanding time in your life. Your life is a River. (I’ve got a whole section on this at the website if you’d like to read a little more about my River analogy.)

So, that means I want you to have “paddles” to use in the canoe for your own River. I have three Paddles for you to consider from this story about the Eisenhower-Marshall meeting of December 14, 1941. Our overall theme with this story is leadership and communication.

Paddle 1: A leader sets the tone and tenor for communication.

Marshall had a very clear way of communicating. Eisenhower hadn’t seen it in action until the Sunday meeting. He saw immediately that Marshall had a particular bluntness and directness. The question would be how deep such conduct ran in Marshall’s larger behavior. Eisenhower knew Marshall by reputation and could expect the bluntness and directness defined his boss. It was true: there wasn’t any open gap or inconsistency between how Marshall communicated with Eisenhower on that Sunday afternoon and everything else Marshall did. Marshall made it that way and Eisenhower learned the truth of it in their conversation.

What tone do you set in your communication?

Paddle 2: Real risk exists in real communication.

Simple, yes. Obvious, yes. But when you consider the presence of risk in the brief Eisenhower-Marshall story, you begin to see the magnitude and depth of the point. Eisenhower accepted, instinctively, that a risk existed in his direct reaction to Marshall’s direct question. More than that, he multiplied the risk by seeking more time and implicitly acknowledging that he’d be back to give his full thoughts. This was all high-wire and no net. Eisenhower lived the risk in those few minutes and then those few hours. If Eisenhower backs away from the risk, this meeting has an entirely different outcome and, likely, aspects of World War Two take a different turn.

Paddle 3: Communication is the beginning of responsibility.

Eisenhower’s first answer, which is really the offering of a question, automatically entails a responsibility he has to his boss. By framing a length of time (a few hours) he has committed to not wasting the time of his boss upon his return with his well-considered thoughts. He has allowed his boss to attach a steeper curve of expectations of the result that Eisenhower will now communicate.

That’s all for now. Thank you very much for walking through this amazing story. I have a million of these as a consulting leadership historian. I’m happy to talk about my history-based approach to leadership development for you, your team, or your organization. Feel free to reach out to me at any time.

All the best, Dan