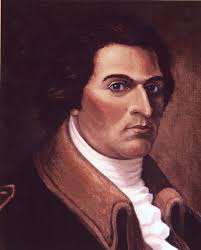

Benedict Arnold. If you know the name you know why. He betrayed the American cause in the Revolutionary War. Switched his loyalty to the British in exchange for money and status. In America, his name is synonymous with treason, back-stabbing, the worst kind of sell-out.

I still want you to know something different about him as a leader.

He had the unique ability to make swift decisions in the middle of crisis, in the heat of the moment. To illustrate, walk with me through two hours in the late afternoon of October 7, 1777. We’ll see Arnold make four decisions in these 120 minutes.

Decision One: he is standing with his superior, General Horatio Gates, in Gates’s headquarters. They despise each other. Without warning, the sound of cannon and gunfire starts outside in the distance. Arnold argues with Gates about the meaning of the sound. They know the enemy is nearby. They suspect a battle with the enemy, the second in three weeks, is beginning. Arnold yells at Gates that he won’t just stand there and do nothing. Gates snarls back that he doesn’t trust Arnold. Ignoring Gates, Arnold runs out of headquarters, grabs a horse, and gallops off towards the sounds. That’s Arnold’s first decision, to act.

Decision Two: he and a trusted colleague, Dan Morgan, are with a large number of American soldiers at the scene of fighting. They can see over the fields that one particular enemy soldier, mounted on a horse, is directing enemy units. Arnold decides quickly that the elimination of this person could greatly benefit the American side. He urges Morgan to select his best sharpshooter to fire on this one enemy soldier. Morgan complies, picks his marksman, who promptly climbs a tree and on the third shot, hits the enemy soldier. That’s Arnold’s second decision, to delegate to a subordinate who in turn delegates to his own subordinate, for the purpose of fulfilling an important task defined on the spot.

Decision Three: he senses that an opportunity, almost invisibly, has arrived when the battle might be won. Arnold believes that this opportunity is best seized a few hundred yards away from where he is now. Still on his horse, he spurs the animal into a full sprint across an open field–in between both the American and British armies firing at each other across this same open space where Arnold is racing with his horse. Through the hurricane of bullets he arrives at his destination without any wound or injury. In this third decision, Arnold blends action with a total disregard of his personal condition. His immediate, self-appointed goal–to arrive at his destination–outweighs every risk to him.

Decision Four: after arriving at his destination, Arnold leads a group of American soldiers into an enclosure, a loose sort of dirt structure, built by the enemy. A key collection of enemy soldiers have gathered here. Again still on horseback, Arnold bursts into the enemy space. The enemy is confused, uncertain, and demoralized by the presence of Arnold and his men. Just a few of them manage to fire their weapons toward Arnold’s force. Enemy surrender is only seconds away. This is Arnold’s fourth and final decision of the two hours, made around 6pm; he drives his followers toward and through the finish, the conclusion, of their dramatic effort. They feel a momentum which he both helps generate and refuses to allow them to give up. Months later, the victory of October 7, 1777 results in French recognition of American independence and much-needed French aid in the American war against Britain.

The victory has a cost, as all victories do. Among the many wounded is Arnold himself, with a bullet fired point-blank into his left femur. The bone explodes. Enough velocity is left over from the blast that the bullet also kills the horse Arnold was riding.

In mysterious fashion, as his horse dies on top of him, Arnold half-smells the future. He confides to a friend an hour later that he wished he’d died along with the animal. Why does he say it? Perhaps Arnold knows Arnold best. As it turned out, the wound hurled Arnold onto a downward path of resentment, jealousy, hostility, bitterness, and revenge. New decisions beckoned along the descent. Treason awaited.

Indeed, had the bullet struck higher, in the chest, or had the wound produced a deadly decline–as often happened in such cases in the Revolutionary War–you and I would know a different Benedict Arnold today. We’d celebrate him for battlefield heroics. We’d marvel at his personal sacrifice. We’d honor him for an inspirational story of bravery and fortitude. But we can still do what ought to be done. We can still acknowledge that on a long-ago October 7, a Tuesday, Benedict Arnold was an extraordinary leader on a day of deeds.

Thanks for reading. All the best, Dan