You quit. You resign. For reasons that are dreadfully important to you, you’ve decided that enough is enough and it’s time to leave your current position. Goodbye.

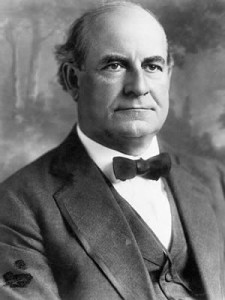

Have you ever been in such a situation? Do you ever expect to be here? Have you seen someone else do something like this? 101 Junes ago, in the last month of spring 1915, William Jennings Bryan was in a spot exactly like this.

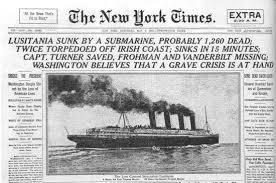

Bryan was Secretary of State, a leader of the US State Department and the nation’s formal chief leader of its foreign relations. He reported to the American President, Woodrow Wilson. On Tuesday, June 8, Bryan resigned from his position.In Bryan’s case, the resignation and the decision to leave were wrapped up in the Great War. Bryan opposed American involvement in the European war, regardless of the two sides then in conflict (Britain, France, Russia, and allies pitted against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and allies). The specific issue triggering Bryan’s departure was the German sinking of a British passenger ship. Killed on board were 128 Americans.

Wilson’s public response to the act was, for Bryan, too aggressive, too closely aligned to the British side and too starkly aligned against the Germans. Rather than sign the public document of official American protest, Bryan resigned during a Cabinet meeting on that Tuesday in early June.

I’d like to walk you through a few details of Bryan’s experience. They might illuminate your own story of purposeful leaving.

First, Bryan’s decision reflected a big cause. His was a world war and the possibility of having the United States pulled into it. He wanted to avoid that at all costs.

Second, the tension between Bryan and his boss (Wilson) built up over a period of several months. Bryan feared that Wilson disagreed fundamentally with Bryan’s desire to stay out of war. At root, Bryan sensed Wilson sympathized with one side in particular, the British. Bryan felt he was constantly trying to overcome Wilson’s inclination.

Third, Bryan’s access to Wilson was not what he wanted it to be. As the President’s chosen Secretary of State, Bryan should have enjoyed dominant, easy, and nearly definitive access to Wilson. That wasn’t the case, in large part because of the presence of the war as a major issue of the day. Bryan’s own subordinate—State Department attorney Robert Lansing—had better access to, and influence on, Wilson. Lack of access was an ongoing irritant.

Fourth, a major event shocked an uneasy status quo. The event was the sinking of the ship Lusitania. That event prompted Wilson to act. The massive scale of the event pushed Wilson toward an outcome that almost by its nature would violate Bryan’s advice and position.

Fifth, the uneasiness of the status quo kept things in perpetual turmoil. I’m referring not only to the decisions of the two sides in the war (Britain announced a total blockade of the European continent while Germany announced the use of unrestricted submarine warfare) but also to the nature of methods at the time. These methods involved a new form of war-making: the submarine. No one had seen submarine warfare to the extent that Germany had used it thus far. This new technique disrupted established habits. Bryan’s decision to leave purposely occurred in the whirlwind of submarine technology.

Do any of these five things look familiar to you?

For your leadership right now, in a team or group or organization, is there a line that you cannot cross?