Americanism Redux

July 16, 250 years ago today

July 16, 250 years ago today

My best friend. Does she think I don’t care anymore?

Holding a letter signed and sealed and sent from Newport, Rhode Island, the 19-year old girl reads the lines and realizes her best friend didn’t receive the last letter she’d written a while ago. The thick paper shook slightly in her thin, almost frail hands.

She is finally feeling better after a difficult winter and spring. Illness stalked her, likely the ongoing effects of having been born very small and vulnerable to sickness. She is prone to problems of the body.

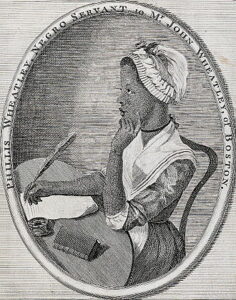

Her spirit, or her soul as she calls it, is among the most powerful forces on earth. No one who looks at her would have thought it, but everyone who listens to her or reads her writings would have known, in an instant, the truth of the power inside her. The frail hands don’t matter.

She knows God and God’s faith. She dreams of it, speaks of it, writes of it, imagines and perceives and nurtures it. Above all, she creates finely crafted poetry about it.

Her goal in life is to live her faith, now on earth and soon in heaven, whenever she arrives. Her dependence on faith is her freedom in life, death, and afterlife.

She is enslaved, a young black girl, the human property of two humans she calls “my master and my mistress.”

Not knowing what to call her when they handed over the money to the slave seller, they had looked at the vessel that brought her to the New World. The Wheatleys had read the letters painted on the side of the vessel—P/h/i/l/l/i/s—and the girl became, since that day eleven years ago, Phillis Wheatley.

On that boat as a child she had met another girl, slightly older than herself, Arbour. Together they endured the experience of enforced transport across the Atlantic Ocean. For Africans like themselves, the two girls descended into the worst human capabilities of invention and instinct, the Middle Passage where sharks followed the ships to eat the bodies thrown overboard and other ships kept their distance to avoid the stench billowing from the hold.

A few years after the journey, Phillis and Arbour renewed their relationship in a chance encounter in Rhode Island, where Arbour lived as an enslaved servant. Since then, in these past several months, they were drawn ever closer together as two young black people–girls in years but women in time–living in the British colonial region of New England. Phillis had written a poem for Arbour that she entitled “On Friendship.”

Today, Phillis worries that her missing letter to Arbour might give her dearest friend the wrong impression of a dying relationship. In brighter moments, though, Phillis will know that the power of God’s love overcomes all, whether the mistake of a lost letter or the misdeed of prejudice and injustice.

And now, 250 years ago, Phillis seeks a quiet place to pray before finding a quill pen and blank parchment paper.

Also

The Wheatleys had immediately recognized Phillis’s extraordinary gift for learning and expression. With their children assisting, they educated her in such classical subjects as Greek and Latin along with extensive readings of the Bible, Homer, Horace, Virgil, Alexander Pope, and John Milton. She absorbed every word and began to write passages, essays, and poems of her own. By summer 1772 Phillis Wheatley possessed a growing reputation in the British colonies of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. The Wheatleys encouraged her work and her Christian faith.

Phillis embraced her Christianity as a source of power and purpose beyond the box and cage of daily life. The Wheatleys praised Phillis’s religious faith as an example of transformation across the world.

Every British colony in North America had enslaved people. The predominant group of enslaved people were African or of African descent. Enslaved Native Americans were evident, too, though on a miniscule scale compared to the number of Black people in enslavement.

Slavery was not limited to the British colonies as places of enslavement or Black people as targets for enslavement. It had been part of cultures and communities in every corner of the planet. And within the thirteen British colonies along the Atlantic Coast of America in 1772, the story of slavery varied, shifting in practice and policy, habit and custom. The straight and unbroken lines of cause and effect were few and far between. Indeed, it was the twisting and writhing nature of slavery that made it so pervasive and complex in the British colonial world of 1772.

From seedling to sapling, the young tree grew and as it did, a vine rose from the soil, clinging to the branches. New leaves and new twigs marked the tree’s growth, yet never far away was the relentless vine, curling and winding.

So it was in the story of the Garden that Phillis knew well.

You Now

We can fail to appreciate the heights to which people can rise, the feats they can accomplish and the resilience they can display. At the same time, we can fail to appreciate the depths to which people can sink, the horrendous manner in which they can insist life must be led. A young girl from the continent of Africa acquired a new name not of her choosing on the continent of North America, after having in-between seen a floating world that beggared description. Yet she wasn’t done and she wasn’t done in. She prevailed. She persevered. She prospered in a way of living that many people would admire and aspire to replicate. She had arrived at today 250 years ago through the help of people who, with whatever their own limitations, sensed the limitless gifts instilled in her before she was born. Instilled in you and her alike are the gifts meant to be known, unearthed, polished, and shined.

Suggestion

Take a walk with Phillis in the Garden, savoring a freedom from the limits designed to hem you in. Begin with the steps that remove your own recriminations. The nation desperately needs it.