Americanism Redux

August 31, 250 years ago today

The eye stares down. The eye sees all.

Under the gaze of the eye stands a little church where, yesterday, a small group of people had gathered to worship, to sing, to pray, to hear a sermon. They didn’t know the eye would soon move over them. In its gaze.

Midnight nears. Horror looks different in the dark.

During the four hours before midnight, winds howled, rain blasted, lightning streaked the sky and struck the ground and anything on it. The little church reflected flashes of light and then reverted to darkness. Thunder shook the rafters and water lashed the windows.

(where the original church stood)

Away from the church, the worshippers cried out in their homes. Where art Thou? They huddle in terror, quivering in wooden houses and cabins. They weep in pain and suffering.

Then the eye came. Is this Thou? In the eye’s sight, calm, an eerie peacefulness above the little church. Midnight creeps closer, time moves ahead, and the eye turns away. Behind it is the rest of the body of the storm, swallowing and smothering the island. The little church disappears and then reappears.

There is more terror, more panic, more wailing and shrieking among the worshippers during the next hours of rain, wind, and lightning. Fiery objects burn across the sky. The air smells of gunpowder, the water tastes of sulphur.

When dawn comes up, the people of St. Croix will begin the first day of life after the hurricane that devastated many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea. Time moves on.

(St. Croix)

A man—a father with two young children and a teenager whom he mentors—wipes his face. Rain, sweat, and tears soak his skin. Beneath wet hair, his mind remembers a reading. Dante wrote about the circles of Hell.

The storm lives as a circle.

The living, killing thing spins and turns and wheels beyond St. Croix, northwest through the Caribbean Sea.

Also

The man is Reverend Hugh Knox. He is pastor of the small Presbyterian Church on St. Croix. Well-read and with a thoughtful, reflective bent of mind, Knox will begin to write a sermon about the hurricane, both its effect and its meaning. Knox knows that his congregation—his spiritual family as well as his household family—will look to him to help make sense of the senseless, to offer a path out of the pain, grief, and suffering that engulfs his worshippers. Many of them will be homeless, will have no clothing or food, and are at great risk of disease from foul water. How does a loving God allow life to be lived thus?

Beginning 250 years ago today, Knox will take the rest of this week to work on his sermon for the upcoming Sunday, six days in the future. He’ll read the Bible, consulting the Books of Job, Jeremiah, Isaiah, the Psalms, among others. He’ll study the stories of people who see themselves as a unit, a chosen few, and how they endured unexpected torment from an enraged nature. More than anything else, he’ll seek to know how to say in words the truth of God’s continued presence and of a better time coming. God, Knox knows, is more than the eye. God, Knox wonders, may have made the eye. God, Knox believes, will tell him one day.

If Knox is blessed or lucky or something else, he may succeed in helping his congregation see beyond now, today, 250 years ago. He can make a difference to his people in the damp pews of a thrashed church. But he has to speak and they have to hear. He must reach a hand into their stunned lives and help pull them back onto a narrow path.

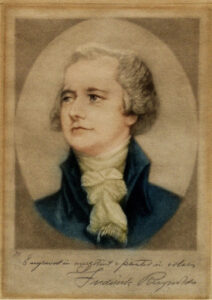

On the sixth day from today 250 years ago the teenager Knox mentors, Alexander Hamilton, will be listening from a row of seats under the shaken rafters. Practically leaping from the pew, he will be inspired by what he hears from Reverend Knox and will want to discuss—now!—the sermon he’s just heard. Set emotionally on fire, his intellect ignited, white-hot with zeal, Hamilton will feel moved to write his own words, his “self-discourses” as he calls them. His quill pen will blaze across the parchment in writing about the hurricane’s physical effects and spiritual importance. He’ll also write about “The Man”, his reference to the impressive leadership shown in the crisis by the Governor-General of St. Croix, Ulrich Wilhelm de Roepstorff, roughly the same age as a Virginia planter named George Washington whom Hamilton has yet to meet.

(a youthful-looking Alexander Hamilton)

So, emerging in the wake of the hurricane, inspiration flows from the scene to Knox, from Knox to Hamilton, from Hamilton to the local readers of his self-discourses. They will be stirred to their own actions, a rapid gathering of money to pay for the teenager’s relocation 1,600 miles north to the British colonial city, New York City, and the college education which they believe he richly deserves from their life investment.

Blinking, winking, shifting, closing, the eye sees all, 250 years ago today.

For You Now

Your mind can go to two places.

You can think of the hurricane as a symbol of the storms that roar into our lives and the aftermath they produce. The forces of nature destroy, upend, overturn. They can kill and maim. They take a life and tear it to shreds. They are rabid, sinking dripping teeth into soft flesh.

It occurs to a person and to a community, to a space and to a place. It is a moment in time that wasn’t there, happens, and is there no longer. But it doesn’t stop, it doesn’t end, it doesn’t disappear. Blood dries but skin scars.

The questions pivot on the aftermath. What resulted? What came about? What replaced? What continued and what was born new and born anew?

Is this how the storm relates to the American Revolution? Is it a symbol of founding?

You can also think of the hurricane as fate and the threads of drama unspooling.

The link between Knox and the teenager in the pews. The link between the teenager and the people impressed with his gifts. The link between the teenager given an opportunity that becomes a reality still forming in the stratosphere. The link between the stratosphere and the twinkling lights that the eye always sees but which we only glimpse through probes deep in the blackness.

The questions are a version of a shake of the head. Who could have known? Who could have foreseen? Who could guess? Who could predict? And yet, who doesn’t see with eyes of their own a life surely meant to storm, a tempest if one ever was.

Is there amongst us today, pulling back into now from 250 years ago, something and someone similar at work? Will we, years ahead, look back and see the invisible made plain and rendered obvious? Was it all ordained and destined?

Can a nation, or a person, be born again and must the rebirth be in a storm?

Suggestion

How do you know when you’ve seen a symbol of something larger than yourself?

(And a little something more…)

Hamilton’s letter:

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0042

Hurricane song, the musical Hamilton: