Americanism Redux

December 21, 250 years ago today (1772)

On a ship, today, 250 years ago, he looks at the Florida coast. But a lifetime ago he was somewhere else, looking at a moment that would begin to define his life.

*******************************************************************************************************

He feels the cave’s walls on his body. He clutches a small torch in one hand, a loaded gun in the other. It takes amazing strength in his upper body to keep crawling forward into the cave. He shoves with his legs, pulls with his elbows. Around one of his legs is a rope, tied and fitted, scratchy against him. The length runs behind him, out of view. Moisture dampens his frizzy hair and round face, a combination of sweat and rainwater.

On he goes. The torch’s dancing light scatters the black into dark, the dark into gray, the gray into gold. Color shimmers. Then he hears a noise not of himself. In waves bouncing off the rock, echoes amplify the snarls and growls. He slides closer, light and sound confusing the distance. He imagines bared fangs, curled lips, a wicked snout ready to gash into his face, neck, and shoulders. Now he sees and hears together, the sight with the sound. Torch-light reveals a gigantic animal, glowing eyes, and small, moving shadows behind. The mother protects her pups. Saliva drips from the snapping mouth, the head cutting and twisting in small lunges toward him. Stay away. On he comes.

Men and women wait outside the cave. They listen for sounds. They hold the rope, waiting for a tug or jerk. They’re fishing for the end of the story and, they hope, the end of a wolf that has terrorized local sheep, calves, and chickens.

Bang! Smoke drifts from the cave.

A yell or shriek or something. The rope jumps from their hands.

A moment or two more and out crawls Israel Putnam. Bloodied, dirty, wet, smoke-stained, disoriented.

And smiling, strangely.

The wolf is dead. He killed the wolf.

He returns to the cave, crawls back inside, and signals with the rope for the people to pull. Out they are dragged, at the end of the line, the hero-man and the slaughtered beast.

It is 1750 and Putnam’s life is never the same after.

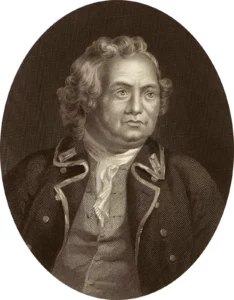

(Israel Putnam)

Also

Today, December 21, 250 years ago, Israel Putnam is aboard ship off the Florida coast. Warmer waters, warmer air, sandy beaches and lush coastal forests, Putnam enjoys the smell of ocean salt. He’s seeking open land that he can settle, perhaps colonize with a group that he leads.

He’s simply not satisfied. Never is, really. He had built from his legendary wolf story and served as an officer with his own Connecticut unit back in the French and Indian War. Putnam had become a special sort of soldier, however, a “ranger.” It was a word that meant something very unique—a talent for hit-and-run ambushes and raids, a willingness to use a type of violence that might not be true in formal, pitched battles, and a deep dependence on shock, speed, and surprise in combat. A victim of ranger attacks, of irregular warfare (or bush warfare as the British called it or la petite guerre as the French called it), might be a woman or child as much as a man, a civilian as much as a soldier. Israel Putnam was a ranger, an irregular, a guerrilla. He was more comfortable in combat with Natives than he was with Europeans or ordinary colonists.

If organized violence becomes an answer again, after 1772, Putnam will approach it with a particular background and experience. And that fact might not express the Cause in a way everyone likes or admires. For now, though, he scans the shores of Florida and wonders who he knows as a possible contact and person of influence for the settlement he craves.

The same is true for Robert Rogers today, 250 years ago. He was a comrade of Putnam’s, though from Massachusetts. Rogers had become a colonel in the French and Indian War, a rank he gained exclusively from his talent at irregular warfare. Indeed, a unit became known as “Rogers’s Rangers.” The stories circulating about his wartime exploits, some of them with a disturbing degree of cruelty, make him well-known. He has written a book to capitalize on his notoriety.

Like Putnam, Robert Rogers wasn’t an easy fit into civilian life. Unlike Putnam, Rogers went further in seeking to scratch the itch by plunging deeply into debt, conducting unethical land deals, and even becoming accused of treason for questionable conduct in the British fort named Michilimackinac where the Great Lakes Michigan and Huron touched together.

Now, as Christmas approaches in 1772, he sits in a debtor’s prison in London. Think, think, he commands himself, how can I get out of this wretched hellhole and get what I want? A British general? A politician? Who do I know who will help me?

(Robert Rogers)

George Washington has a military background that runs alongside Putnam and Rogers. Before he became a formal commander in the French and Indian War, Washington’s first exposure to battle was in May 1754. In a form that Putnam and Rogers would come to perfect, Washington and a handful of colonial soldiers joined with Tanaghrisson, a Native leader the British called Half-King, and warriors from the Seneca and Catawba tribes. Washington and Tanaghrisson planned and executed a surprise, shock attack on French soldiers near Great Meadow in western Pennsylvania. Scalping of the dead or wounded French occurred; one observer referred to it as an “assassination” and the men who did the deeds as “assassins.”

(Tanaghrisson)

(George Washington near Great Meadow)

250 years ago today that’s the heritage of warfare in North America. That’s the identity that some people in North America will seek to perpetuate. That’s the culture of war in the waters and in the woods where Putnam seeks a life, Rogers seeks a fortune, and Washington seeks personal independence as a wealthy agriculturalist, landowner, and labor enslaver.

For You Now

Identity is a tricky thing. There is the identity of within, made by you and yourself. There is the identity of without, made by others, by them and themselves. The two might match, but no guarantee of a match should be assumed. They can even match but follow entirely different paths in getting to the same point. Tricky.

Still more, identity gets complicated as the numbers rise, from one to many and from many to collective. The complications compound when you jump from here to there—the identity of one aspect shared across space and time to another aspect. And we haven’t even talked about the byzantine challenges of finding identity in an event or a result. But here we are, exploring the American Founding and searching for signs and traces of identity. A good quest.

Putnam, Rogers, Washington and the way of organized violence and directed mayhem. The chosen manner of armed force will reveal part of the identity each embraces as 1772 bids goodbye.

Suggestion

You see war right now. You have an expectation of the allowed and the disallowed in war. Consider your expectation of how significant war should be in understanding the Founding. Consider how far you will comfortably go in your expecation and at what point, if any, you will stop and say it’s too far.

(near the site of Washington and Tanaghrisson’s irregular attack)